Popular Woodworking 2001-02 № 120, страница 32

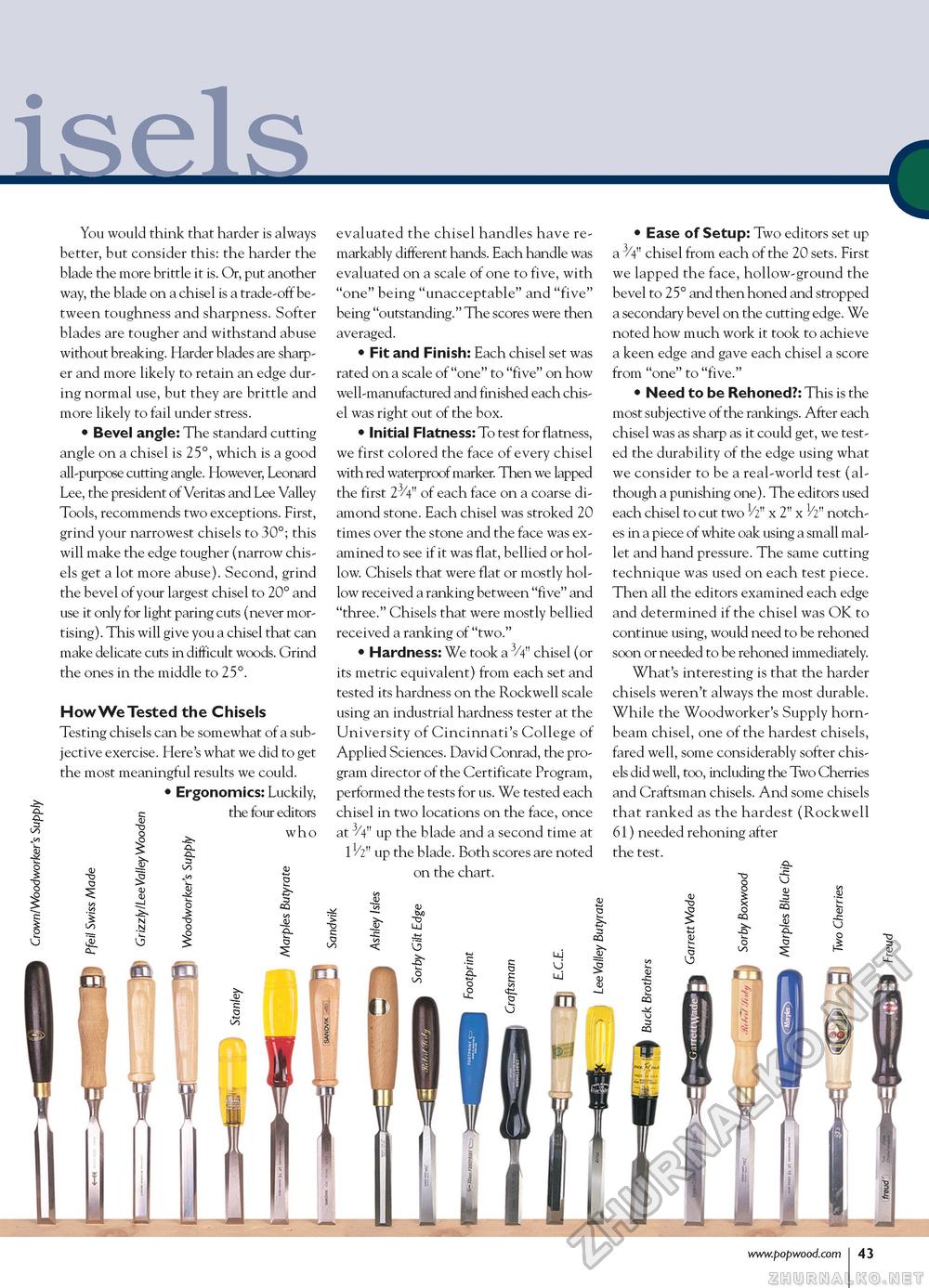

isels5 "o ! U You would think that harder is always better, but consider this: the harder the blade the more brittle it is. Or, put another way, the blade on a chisel is a trade-off between toughness and sharpness. Softer blades are tougher and withstand abuse without breaking. Harder blades are sharper and more likely to retain an edge during normal use, but they are brittle and more likely to fail under stress. • Bevel angle: The standard cutting angle on a chisel is 25°, which is a good all-purpose cutting angle. However, Leonard Lee, the president of Veritas and Lee Valley Tools, recommends two exceptions. First, grind your narrowest chisels to 30°; this will make the edge tougher (narrow chisels get a lot more abuse). Second, grind the bevel of your largest chisel to 20° and use it only for light paring cuts (never mortising). This will give you a chisel that can make delicate cuts in difficult woods. Grind the ones in the middle to 25°. How We Tested the Chisels Testing chisels can be somewhat of a subjective exercise. Here's what we did to get the most meaningful results we could. • Ergonomics: Luckily, c the four editors "o who evaluated the chisel handles have remarkably different hands. Each handle was evaluated on a scale of one to five, with "one" being "unacceptable" and "five" being "outstanding." The scores were then averaged. • Fit and Finish: Each chisel set was rated on a scale of "one" to "five" on how well-manufactured and finished each chisel was right out of the box. • Initial Flatness: To test for flatness, we first colored the face of every chisel with red waterproof marker. Then we lapped the first 23/4" of each face on a coarse diamond stone. Each chisel was stroked 20 times over the stone and the face was examined to see if it was flat, bellied or hollow. Chisels that were flat or mostly hollow received a ranking between "five" and "three." Chisels that were mostly bellied received a ranking of "two." • Hardness: We took a 3/4" chisel (or its metric equivalent) from each set and tested its hardness on the Rockwell scale using an industrial hardness tester at the University of Cincinnati's College of Applied Sciences. David Conrad, the program director of the Certificate Program, performed the tests for us. We tested each chisel in two locations on the face, once at 3/4" up the blade and a second time at 11/2" up the blade. Both scores are noted on the chart. • Ease of Setup: Two editors set up a 3/4" chisel from each of the 20 sets. First we lapped the face, hollow-ground the bevel to 25° and then honed and stropped a secondary bevel on the cutting edge. We noted how much work it took to achieve a keen edge and gave each chisel a score from "one" to "five." • Need to be Rehoned?: This is the most subjective of the rankings. After each chisel was as sharp as it could get, we tested the durability of the edge using what we consider to be a real-world test (although a punishing one). The editors used each chisel to cut two V2" x 2" x 1/2" notches in a piece of white oak using a small mallet and hand pressure. The same cutting technique was used on each test piece. Then all the editors examined each edge and determined if the chisel was OK to continue using, would need to be rehoned soon or needed to be rehoned immediately. What's interesting is that the harder chisels weren't always the most durable. While the Woodworker's Supply hornbeam chisel, one of the hardest chisels, fared well, some considerably softer chisels did well, too, including the Two Cherries and Craftsman chisels. And some chisels that ranked as the hardest (Rockwell 61) needed rehoning after the test. I 1 V |