Popular Woodworking 2002-06 № 128, страница 16

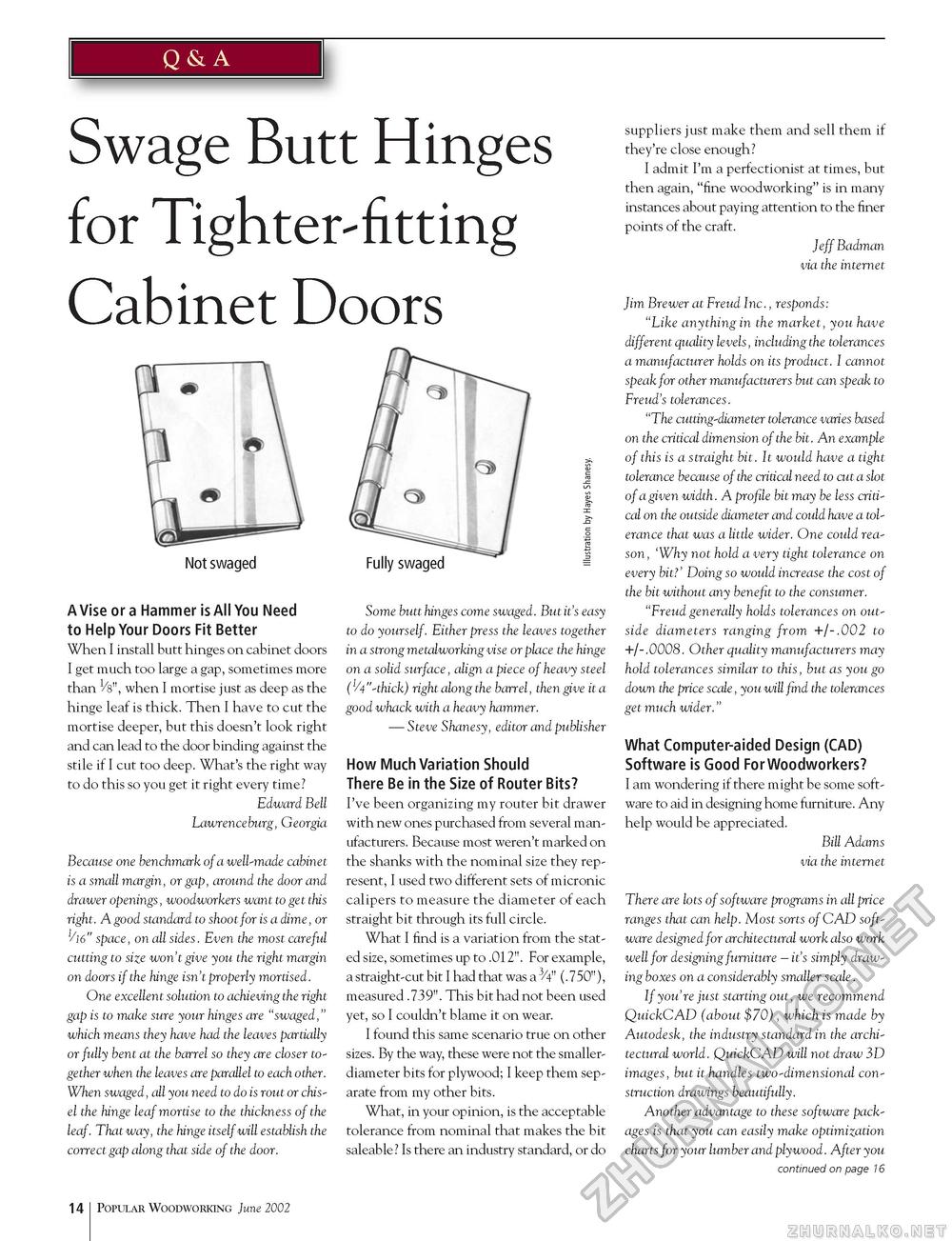

Swage Butt Hinges for Tighter-fitting Cabinet Doors A Vise or a Hammer is All You Need to Help Your Doors Fit Better When I install butt hinges on cabinet doors I get much too large a gap, sometimes more than V8", when I mortise just as deep as the hinge leaf is thick. Then I have to cut the mortise deeper, but this doesn't look right and can lead to the door binding against the stile if I cut too deep. What's the right way to do this so you get it right every time? Edward Bell Lawrenceburg, Georgia Because one benchmark of a well-made cabinet is a small margin, or gap, around the door and drawer openings, woodworkers want to get this right. A good standard to shoot for is a dime, or y/16" space, on all sides. Even the most careful cutting to size won't give you the right margin on doors if the hinge isn't properly mortised. One excellent solution to achieving the right gap is to make sure your hinges are "swaged," which means they have had the leaves partially or fully bent at the barrel so they are closer together when the leaves are parallel to each other. When swaged, all you need to do is rout or chisel the hinge leaf mortise to the thickness of the leaf. That way, the hinge itself will establish the correct gap along that side of the door. Some butt hinges come swaged. But it's easy to do yourself. Either press the leaves together in a strong metalworking vise or place the hinge on a solid surface, align a piece of heavy steel CA"-thick) right along the barrel, then give it a good whack with a heavy hammer. — Steve Shanesy, editor and publisher How Much Variation Should There Be in the Size of Router Bits? I've been organizing my router bit drawer with new ones purchased from several manufacturers. Because most weren't marked on the shanks with the nominal size they represent, I used two different sets of micronic calipers to measure the diameter of each straight bit through its full circle. What I find is a variation from the stated size, sometimes up to .012". For example, a straight-cut bit I had that was a 3/4" (.750"), measured .739". This bit had not been used yet, so I couldn't blame it on wear. I found this same scenario true on other sizes. By the way, these were not the smaller-diameter bits for plywood; I keep them separate from my other bits. What, in your opinion, is the acceptable tolerance from nominal that makes the bit saleable? Is there an industry standard, or do 14 Popular Woodworking June 2002 suppliers just make them and sell them if they're close enough? I admit I'm a perfectionist at times, but then again, "fine woodworking" is in many instances about paying attention to the finer points of the craft. Jeff Badman via the internet Jim Brewer at Freud Inc., responds: "Like anything in the market, you have different quality levels, including the tolerances a manufacturer holds on its product. I cannot speak for other manufacturers but can speak to Freud's tolerances. "The cutting-diameter tolerance varies based on the critical dimension of the bit. An example of this is a straight bit. It would have a tight tolerance because of the critical need to cut a slot of a given width. A profile bit may be less critical on the outside diameter and could have a tolerance that was a little wider. One could reason, 'Why not hold a very tight tolerance on every bit?' Doing so would increase the cost of the bit without any benefit to the consumer. "Freud generally holds tolerances on outside diameters ranging from +/-.002 to +/-.0008. Other quality manufacturers may hold tolerances similar to this, but as you go down the price scale, you will find the tolerances get much wider." What Computer-aided Design (CAD) Software is Good For Woodworkers? I am wondering if there might be some software to aid in designing home furniture. Any help would be appreciated. Bill Adams via the internet There are lots of software programs in all price ranges that can help. Most sorts of CAD software designed for architectural work also work well for designing furniture - it's simply drawing boxes on a considerably smaller scale. If you're just starting out, we recommend QuickCAD (about $70), which is made by Autodesk, the industry standard in the architectural world. QuickCAD will not draw 3D images, but it handles two-dimensional construction drawings beautifully. Another advantage to these software packages is that you can easily make optimization charts for your lumber and plywood. After you continued on page 16 |