Popular Woodworking 2004-11 № 144, страница 109

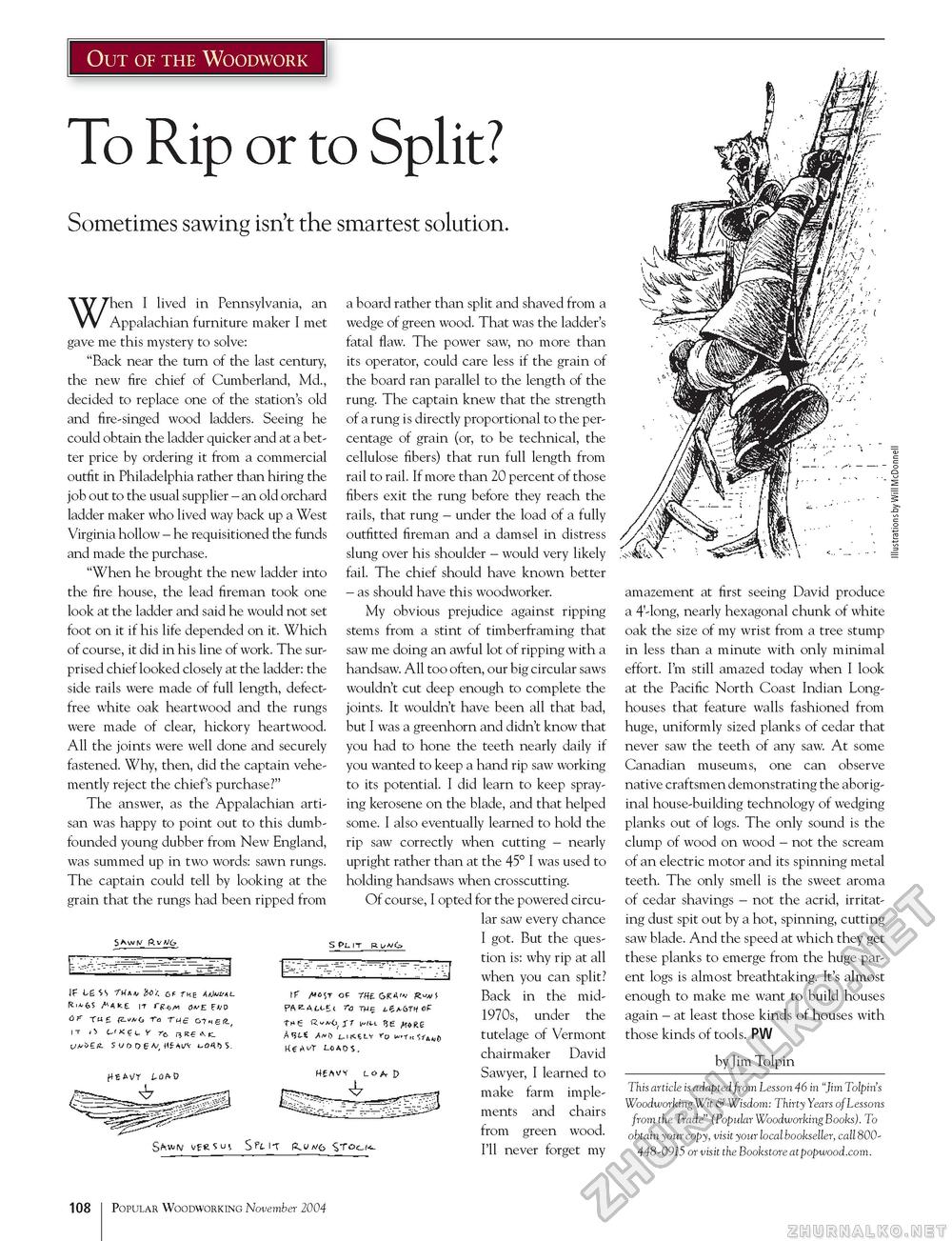

Out of the Woodwork To Rip or to Split? Sometimes sawing isn't the smartest solution. When I lived in Pennsylvania, an Appalachian furniture maker I met gave me this mystery to solve: "Back near the turn of the last century, the new fire chief of Cumberland, Md., decided to replace one of the station's old and fire-singed wood ladders. Seeing he could obtain the ladder quicker and at a better price by ordering it from a commercial outfit in Philadelphia rather than hiring the job out to the usual supplier - an old orchard ladder maker who lived way back up a West Virginia hollow - he requisitioned the funds and made the purchase. "When he brought the new ladder into the fire house, the lead fireman took one look at the ladder and said he would not set foot on it if his life depended on it. Which of course, it did in his line of work. The surprised chief looked closely at the ladder: the side rails were made of full length, defect-free white oak heartwood and the rungs were made of clear, hickory heartwood. All the joints were well done and securely fastened. Why, then, did the captain vehemently reject the chief's purchase?" The answer, as the Appalachian artisan was happy to point out to this dumbfounded young dubber from New England, was summed up in two words: sawn rungs. The captain could tell by looking at the grain that the rungs had been ripped from a board rather than split and shaved from a wedge of green wood. That was the ladder's fatal flaw. The power saw, no more than its operator, could care less if the grain of the board ran parallel to the length of the rung. The captain knew that the strength of a rung is directly proportional to the percentage of grain (or, to be technical, the cellulose fibers) that run full length from rail to rail. If more than 20 percent of those fibers exit the rung before they reach the rails, that rung - under the load of a fully outfitted fireman and a damsel in distress slung over his shoulder - would very likely fail. The chief should have known better - as should have this woodworker. My obvious prejudice against ripping stems from a stint of timberframing that saw me doing an awful lot of ripping with a handsaw. All too often, our big circular saws wouldn't cut deep enough to complete the joints. It wouldn't have been all that bad, but I was a greenhorn and didn't know that you had to hone the teeth nearly daily if you wanted to keep a hand rip saw working to its potential. I did learn to keep spraying kerosene on the blade, and that helped some. I also eventually learned to hold the rip saw correctly when cutting - nearly upright rather than at the 45° I was used to holding handsaws when crosscutting. Of course, I opted for the powered circular saw every chance I got. But the question is: why rip at all when you can split? Back in the mid-1970s, under the tutelage of Vermont chairmaker David Sawyer, I learned to make farm implements and chairs from green wood. I'll never forget my amazement at first seeing David produce a 4'-long, nearly hexagonal chunk of white oak the size of my wrist from a tree stump in less than a minute with only minimal effort. I'm still amazed today when I look at the Pacific North Coast Indian Long-houses that feature walls fashioned from huge, uniformly sized planks of cedar that never saw the teeth of any saw. At some Canadian museums, one can observe native craftsmen demonstrating the aboriginal house-building technology of wedging planks out of logs. The only sound is the clump of wood on wood - not the scream of an electric motor and its spinning metal teeth. The only smell is the sweet aroma of cedar shavings - not the acrid, irritating dust spit out by a hot, spinning, cutting saw blade. And the speed at which they get these planks to emerge from the huge parent logs is almost breathtaking. It's almost enough to make me want to build houses again - at least those kinds of houses with those kinds of tools. PW by Jim Tolpin This article is adapted from Lesson 46 in "Jim Tolpin's Woodworking Wit & Wisdom: Thirty Years of Lessons from the Trade" (Popular Woodworking Books). To obtain your copy, visit your local bookseller, call 800448-0915 or visit the Bookstore atpopwood.com. 108 Popular Woodworking November 2004 |