Popular Woodworking 2005-10 № 150, страница 58

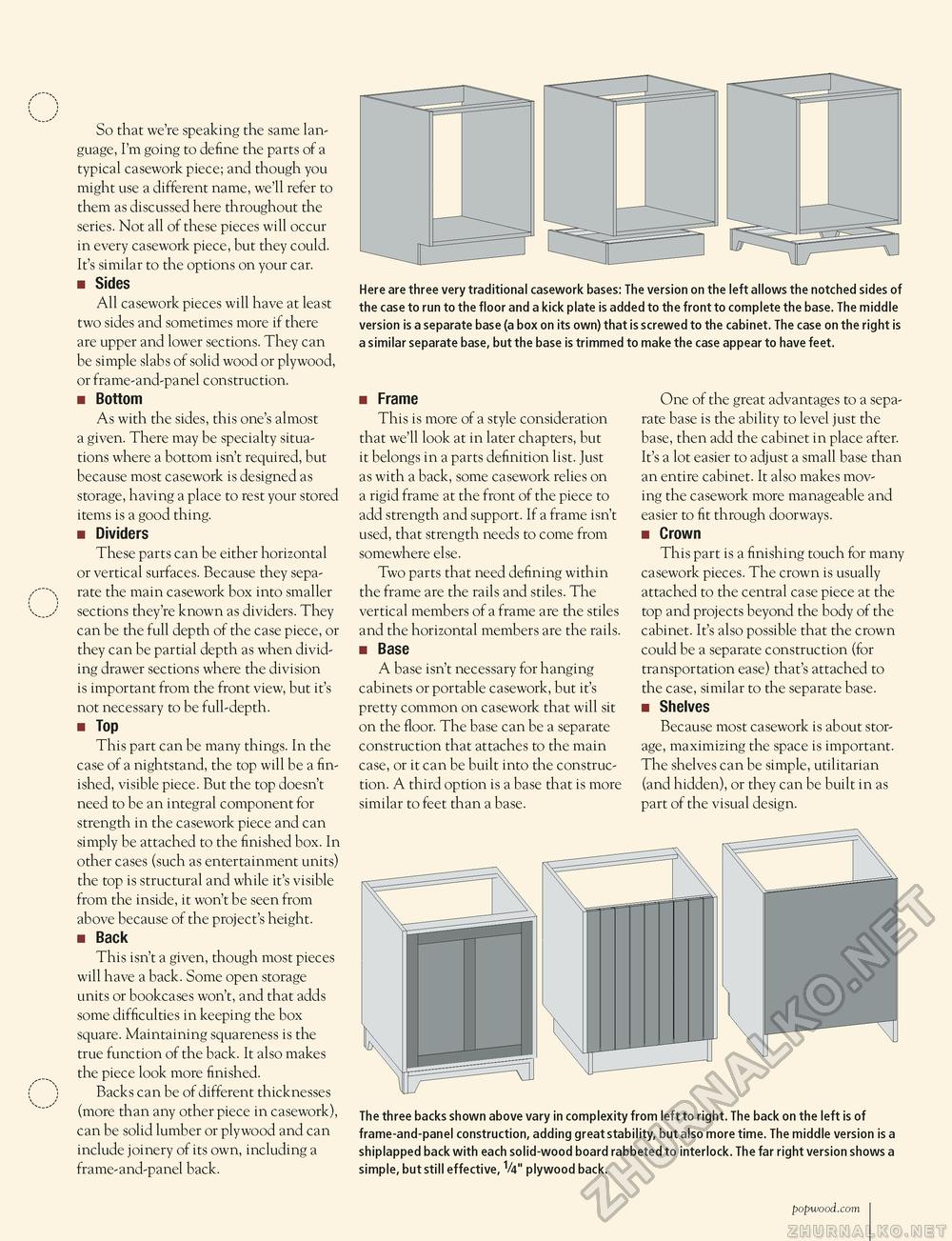

So that we're speaking the same language, I'm going to define the parts of a typical casework piece; and though you might use a different name, we'll refer to them as discussed here throughout the series. Not all of these pieces will occur in every casework piece, but they could. It's similar to the options on your car. ■ Sides All casework pieces will have at least two sides and sometimes more if there are upper and lower sections. They can be simple slabs of solid wood or plywood, or frame-and-panel construction. ■ Bottom As with the sides, this one's almost a given. There may be specialty situations where a bottom isn't required, but because most casework is designed as storage, having a place to rest your stored items is a good thing. ■ Dividers These parts can be either horizontal or vertical surfaces. Because they separate the main casework box into smaller sections they're known as dividers. They can be the full depth of the case piece, or they can be partial depth as when dividing drawer sections where the division is important from the front view, but it's not necessary to be full-depth. ■ Top This part can be many things. In the case of a nightstand, the top will be a finished, visible piece. But the top doesn't need to be an integral component for strength in the casework piece and can simply be attached to the finished box. In other cases (such as entertainment units) the top is structural and while it's visible from the inside, it won't be seen from above because of the project's height. ■ Back This isn't a given, though most pieces will have a back. Some open storage units or bookcases won't, and that adds some difficulties in keeping the box square. Maintaining squareness is the true function of the back. It also makes the piece look more finished. Backs can be of different thicknesses (more than any other piece in casework), can be solid lumber or plywood and can include joinery of its own, including a frame-and-panel back. Here are three very traditional casework bases: The version on the left allows the notched sides of the case to run to the floor and a kick plate is added to the front to complete the base. The middle version is a separate base (a box on its own) that is screwed to the cabinet. The case on the right is a similar separate base, but the base is trimmed to make the case appear to have feet. ■ Frame This is more of a style consideration that we'll look at in later chapters, but it belongs in a parts definition list. Just as with a back, some casework relies on a rigid frame at the front of the piece to add strength and support. If a frame isn't used, that strength needs to come from somewhere else. Two parts that need defining within the frame are the rails and stiles. The vertical members of a frame are the stiles and the horizontal members are the rails. ■ Base A base isn't necessary for hanging cabinets or portable casework, but it's pretty common on casework that will sit on the floor. The base can be a separate construction that attaches to the main case, or it can be built into the construction. A third option is a base that is more similar to feet than a base. One of the great advantages to a separate base is the ability to level just the base, then add the cabinet in place after. It's a lot easier to adjust a small base than an entire cabinet. It also makes moving the casework more manageable and easier to fit through doorways. ■ Crown This part is a finishing touch for many casework pieces. The crown is usually attached to the central case piece at the top and projects beyond the body of the cabinet. It's also possible that the crown could be a separate construction (for transportation ease) that's attached to the case, similar to the separate base. ■ Shelves Because most casework is about storage, maximizing the space is important. The shelves can be simple, utilitarian (and hidden), or they can be built in as part of the visual design. The three backs shown above vary in complexity from left to right. The back on the left is of frame-and-panel construction, adding great stability, but also more time. The middle version is a shiplapped back with each solid-wood board rabbeted to interlock. The far right version shows a simple, but still effective, V4" plywood back. popwood.com i 58 |