Popular Woodworking 2006-04 № 154, страница 16

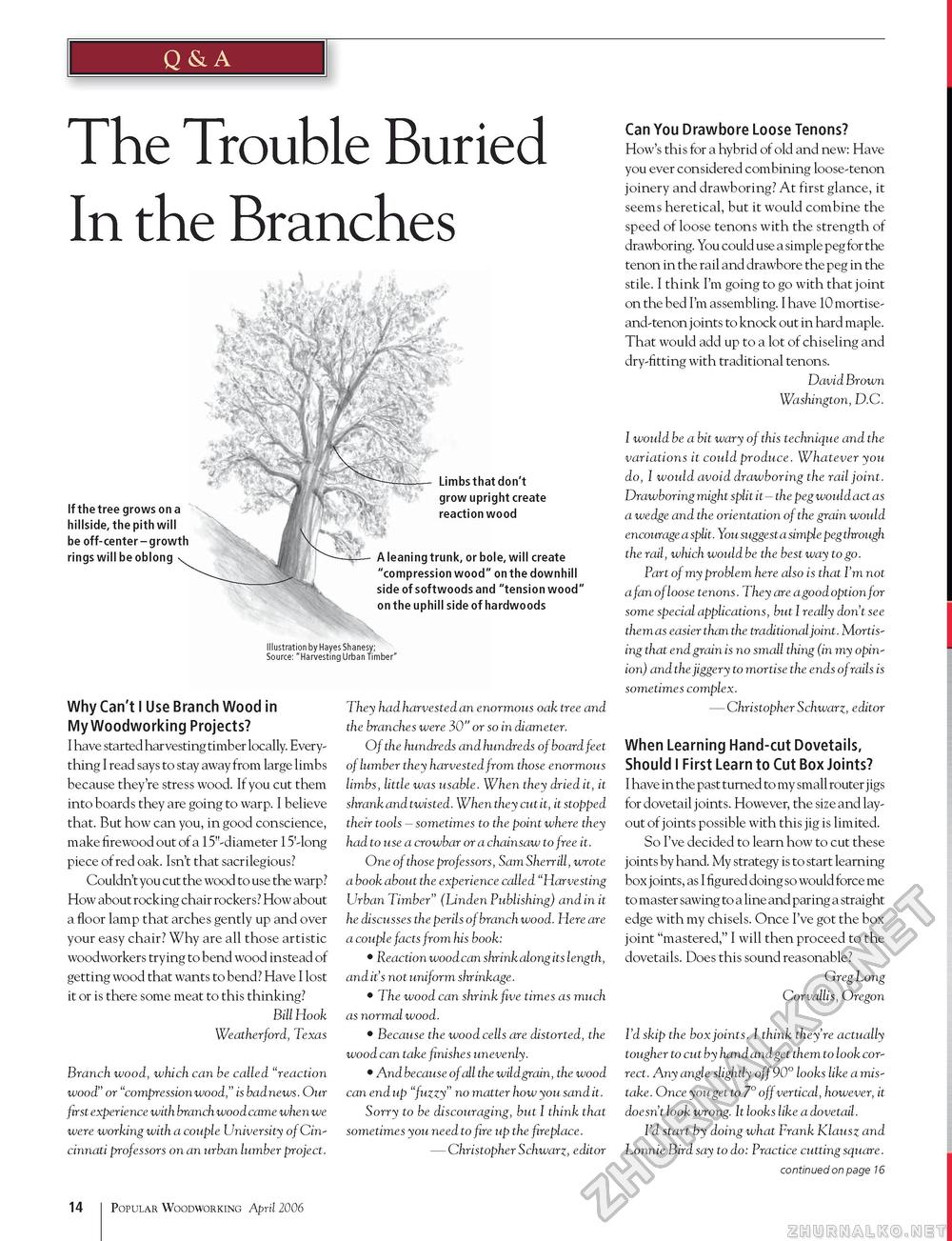

Q & A The Trouble Buried In the Branches If the tree grows on a hillside, the pith will be off-center - growth rings will be oblong fe om m. Limbs that don't grow upright create reaction wood A leaning trunk, or bole, will create "compression wood" on the downhill side of softwoods and "tension wood" on the uphill side of hardwoods Illustration by Hayes Shanesy; Source: "Harvesting Urban Timber" Why Can't I Use Branch Wood in My Woodworking Projects? I have started harvesting timber locally. Everything I read says to stay away from large limbs because they're stress wood. If you cut them into boards they are going to warp. I believe that. But how can you, in good conscience, make firewood out of a 15"-diameter 15'-long piece of red oak. Isn't that sacrilegious? Couldn't you cut the wood to use the warp ? How about rocking chair rockers? How about a floor lamp that arches gently up and over your easy chair? Why are all those artistic woodworkers trying to bend wood instead of getting wood that wants to bend? Have I lost it or is there some meat to this thinking? Bill Hook Weatherford, Texas Branch wood, which can be called "reaction wood" or "compression wood," is bad news. Our first experience with branch wood came when we were working with a couple University of Cincinnati professors on an urban lumber project. They had harvested an enormous oak tree and the branches were 30" or so in diameter. Of the hundreds and hundreds of board feet of lumber they harvested from those enormous limbs, little was usable. When they dried it, it shrank and twisted. When they cut it, it stopped their tools — sometimes to the point where they had to use a crowbar or a chainsaw to free it. One of those professors, Sam Sherrill, wrote a book about the experience called "Harvesting Urban Timber" (Linden Publishing) and in it he discusses the perils of branch wood. Here are a couple facts from his book: • Reaction wood can shrink along its length, and it's not uniform shrinkage. • The wood can shrink five times as much as normal wood. • Because the wood cells are distorted, the wood can take finishes unevenly. • And because of all the wild grain, the wood can end up "fuzzy" no matter how you sand it. Sorry to be discouraging, but I think that sometimes you need to fire up the fireplace. — Christopher Schwarz, editor Can You Drawbore Loose Tenons? How's this for a hybrid of old and new: Have you ever considered combining loose-tenon joinery and drawboring? At first glance, it seems heretical, but it would combine the speed of loose tenons with the strength of drawboring. You could use a simple peg for the tenon in the rail and drawbore the peg in the stile. I think I'm going to go with that joint on the bed I'm assembling. I have 10 mortise-and-tenon joints to knock out in hard maple. That would add up to a lot of chiseling and dry-fitting with traditional tenons. David Brown Washington, D.C. I would be a bit wary of this technique and the variations it could produce. Whatever you do, I would avoid drawboring the rail joint. Drawboring might split it—the peg would act as a wedge and the orientation of the grain would encourage a split. You suggest a simple peg through the rail, which would be the best way to go. Part of my problem here also is that I'm not a fan of loose tenons. They are a good option for some special applications, but I really don't see them as easier than the traditional joint. Mortising that end grain is no small thing (in my opinion) and the jiggery to mortise the ends of rails is sometimes complex. — Christopher Schwarz, editor When Learning Hand-cut Dovetails, Should I First Learn to Cut Box Joints? I have in the past turned to my small router j igs for dovetail joints. However, the size and layout of joints possible with this jig is limited. So I've decided to learn how to cut these j oints by hand. My strategy is to start learning box joints, as I figured doing so would force me to master sawing to a line and paring a straight edge with my chisels. Once I've got the box joint "mastered," I will then proceed to the dovetails. Does this sound reasonable? Greg Long Corvallis, Oregon I'd skip the box joints. I think they're actually tougher to cut by hand and get them to look correct. Any angle slightly off 90° looks like a mistake. Once you get to 7° off vertical, however, it doesn't look wrong. It looks like a dovetail. I'd start by doing what Frank Klausz and Lonnie Bird say to do: Practice cutting square. continued on page 16 14 Popular Woodworking April 2006 |