Popular Woodworking 2006-06 № 155, страница 34

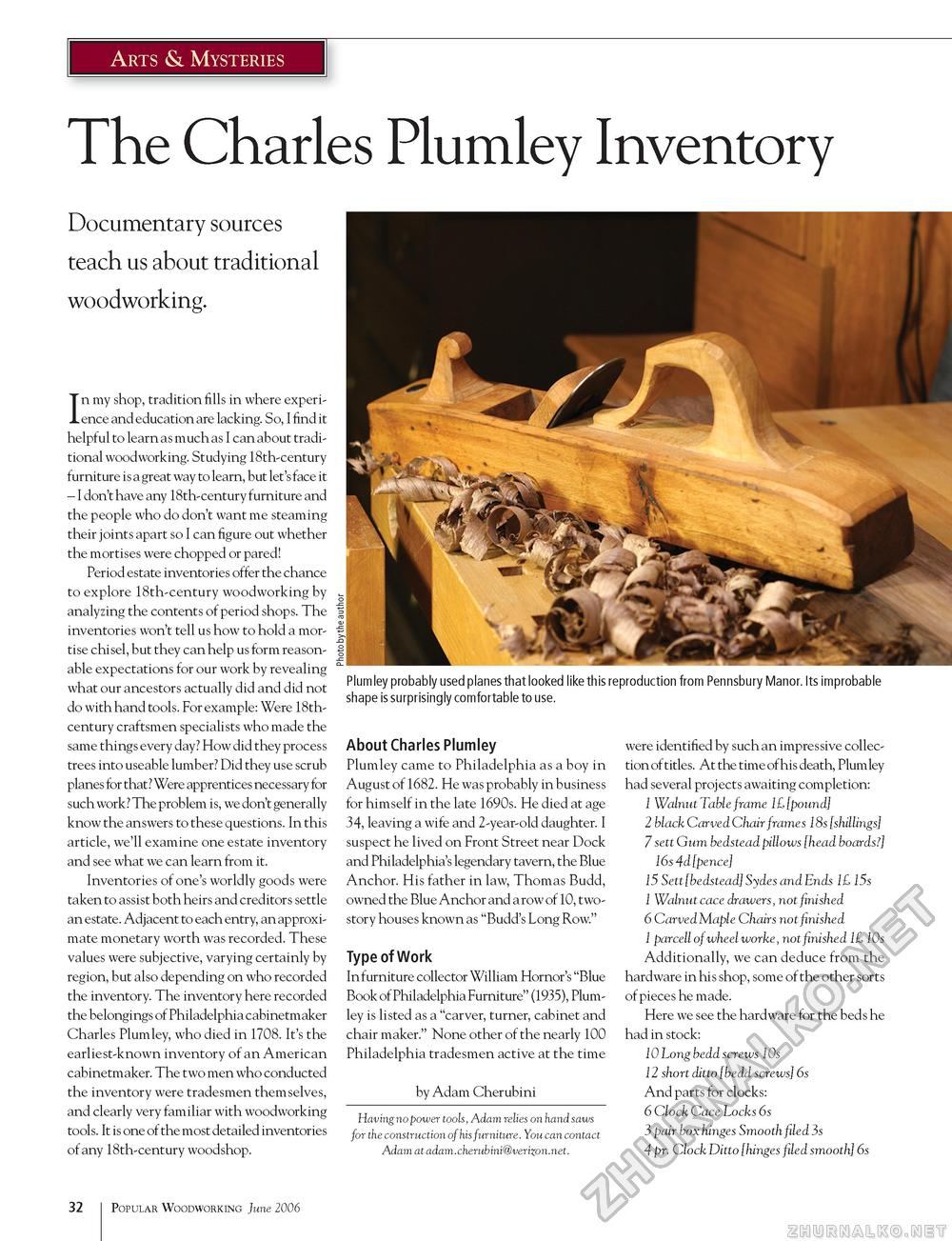

Arts & Mysteries The Charles Plumley Inventory Documentary sources teach us about traditional woodworking. In my shop, tradition fills in where experience and education are lacking. So, I find it helpful to learn as much as I can about traditional woodworking. Studying 18th-century furniture is a great way to learn, but let's face it - I don't have any 18th-century furniture and the people who do don't want me steaming their joints apart so I can figure out whether the mortises were chopped or pared! Period estate inventories offer the chance to explore 18th-century woodworking by analyzing the contents of period shops. The inventories won't tell us how to hold a mortise chisel, but they can help us form reasonable expectations for our work by revealing what our ancestors actually did and did not do with hand tools. For example: Were 18th-century craftsmen specialists who made the same things every day? How did they process trees into useable lumber? Did they use scrub planes for that? Were apprentices necessary for such work? The problem is, we don't generally know the answers to these questions. In this article, we'll examine one estate inventory and see what we can learn from it. Inventories of one's worldly goods were taken to assist both heirs and creditors settle an estate. Adjacent to each entry, an approximate monetary worth was recorded. These values were subjective, varying certainly by region, but also depending on who recorded the inventory. The inventory here recorded the belongings of Philadelphia cabinetmaker Charles Plumley, who died in 1708. It's the earliest-known inventory of an American cabinetmaker. The two men who conducted the inventory were tradesmen themselves, and clearly very familiar with woodworking tools. It is one of the most detailed inventories of any 18th-century woodshop. Plumley probably used planes that looked like this reproduction from Pennsbury Manor. Its improbable shape is surprisingly comfortable to use. About Charles Plumley Plumley came to Philadelphia as a boy in August of 1682. He was probably in business for himself in the late 1690s. He died at age 34, leaving a wife and 2-year-old daughter. I suspect he lived on Front Street near Dock and Philadelphia's legendary tavern, the Blue Anchor. His father in law, Thomas Budd, owned the Blue Anchor and a row of 10, two-story houses known as "Budd's Long Row." Type of Work In furniture collector William Hornor's "Blue Book of Philadelphia Furniture" (1935), Plum-ley is listed as a "carver, turner, cabinet and chair maker." None other of the nearly 100 Philadelphia tradesmen active at the time by Adam Cherubini Having no power tools, Adam relies on hand saws for the construction of his furniture. You can contact Adam at adam.cherubini@verizon.net. were identified by such an impressive collection of titles. At the time of his death, Plumley had several projects awaiting completion: 1 Walnut Table frame 1£ [pound] 2 black Carved Chair frames 18s [shillings] 7 sett Gum bedstead pillows [head boards?] 16s 4d [pence] 15 Sett [bedstead] Sydes and Ends 1£ 15s 1 Walnut cace drawers, not finished 6 Carved Maple Chairs not finished 1 parcell of wheel worke, not finished 1£ 10s Additionally, we can deduce from the hardware in his shop, some of the other sorts of pieces he made. Here we see the hardware for the beds he had in stock: 10 Long bedd screws 10s 12 short ditto [bedd screws] 6s And parts for clocks: 6 Clock Cace Locks 6s 3 pair box hinges Smooth filed 3s 4 pr. Clock Ditto [hinges filed smooth] 6s 32 Popular Woodworking June 2006 |