Popular Woodworking 2006-06 № 155, страница 83

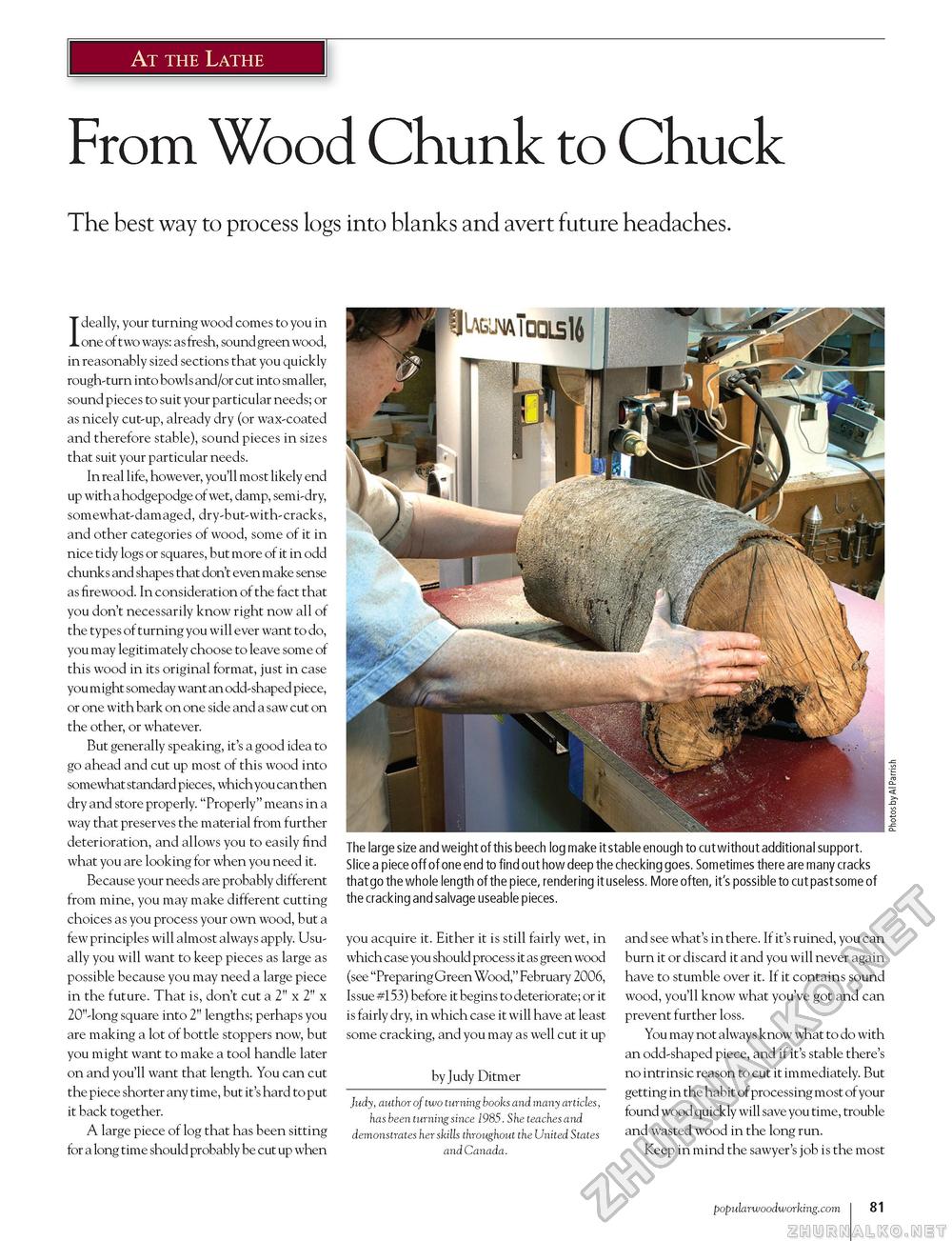

At the Lathe From Wood Chunk to Chuck The best way to process logs into blanks and avert future headaches. The large size and weight of this beech log make it stable enough to cut without additional support. Slice a piece off of one end to find out how deep the checking goes. Sometimes there are many cracks that go the whole length of the piece, rendering it useless. More often, it's possible to cut past some of the cracking and salvage useable pieces. Ideally, your turning wood comes to you in one of two ways: as fresh, sound green wood, in reasonably sized sections that you quickly rough-turn into bowls and/or cut into smaller, sound pieces to suit your particular needs; or as nicely cut-up, already dry (or wax-coated and therefore stable), sound pieces in sizes that suit your particular needs. In real life, however, you'll most likely end up with a hodgepodge of wet, damp, semi-dry, somewhat-damaged, dry-but-with-cracks, and other categories of wood, some of it in nice tidy logs or squares, but more of it in odd chunks and shapes that don't even make sense as firewood. In consideration of the fact that you don't necessarily know right now all of the types of turning you will ever want to do, you may legitimately choose to leave some of this wood in its original format, just in case you might someday want an odd-shaped piece, or one with bark on one side and a saw cut on the other, or whatever. But generally speaking, it's a good idea to go ahead and cut up most of this wood into somewhat standard pieces, which you can then dry and store properly. "Properly" means in a way that preserves the material from further deterioration, and allows you to easily find what you are looking for when you need it. Because your needs are probably different from mine, you may make different cutting choices as you process your own wood, but a few principles will almost always apply. Usually you will want to keep pieces as large as possible because you may need a large piece in the future. That is, don't cut a 2" x 2" x 20"-long square into 2" lengths; perhaps you are making a lot of bottle stoppers now, but you might want to make a tool handle later on and you'll want that length. You can cut the piece shorter any time, but it's hard to put it back together. A large piece of log that has been sitting for a long time should probably be cut up when you acquire it. Either it is still fairly wet, in which case you should process it as green wood (see "Preparing Green Wood," February 2006, Issue #153) before it begins to deteriorate; or it is fairly dry, in which case it will have at least some cracking, and you may as well cut it up by Judy Ditmer Judy, author of two turning books and many articles, has been turning since 1985. She teaches and demonstrates her skills throughout the United States and Canada. and see what's in there. If it's ruined, you can burn it or discard it and you will never again have to stumble over it. If it contains sound wood, you'll know what you've got and can prevent further loss. You may not always know what to do with an odd-shaped piece, and if it's stable there's no intrinsic reason to cut it immediately. But getting in the habit of processing most of your found wood quickly will save you time, trouble and wasted wood in the long run. Keep in mind the sawyer's job is the most popularwoodworking.com I 81 |