Woodworker's Journal 2008-32-3, страница 31

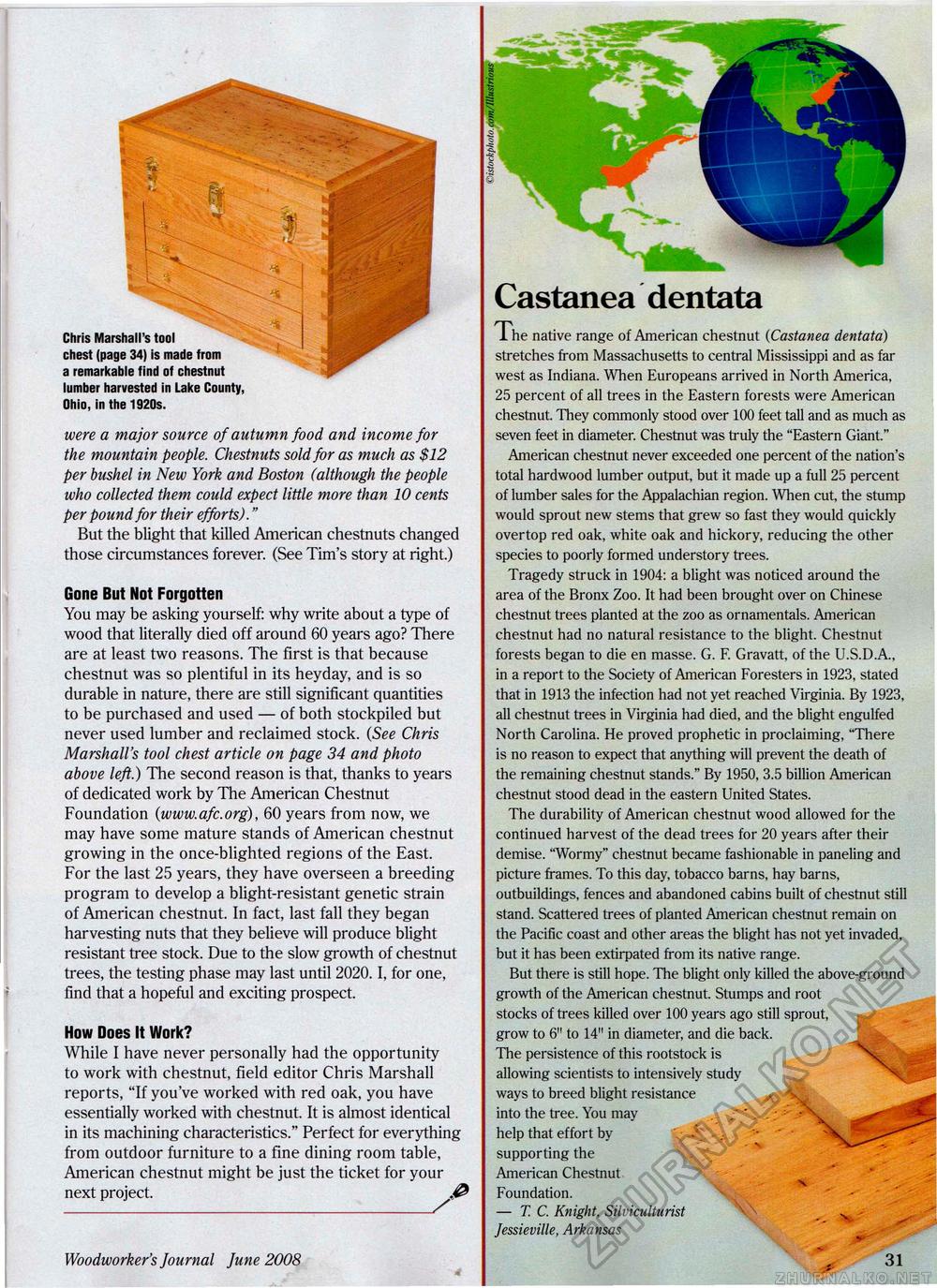

ft. Chris Marshall's tool chest (page 34) is made from a remarkable find of chestnut lumber harvested in Lake County, Ohio, in the 1920s. were a major source of autumn food and income for the mountain people. Chestnuts sold for as much as $12 per bushel in New York and Boston (although the people who collected them could expect little more than 10 cents per pound for their efforts)." But the blight that killed American chestnuts changed those circumstances forever. (See Tim's story at right.) Gone But Not Forgotten You may be asking yourself: why write about a type of wood that literally died off around 60 years ago? There are at least two reasons. The first is that because chestnut was so plentiful in its heyday, and is so durable in nature, there are still significant quantities to be purchased and used — of both stockpiled but never used lumber and reclaimed stock. (See Chris Marshall's tool chest article on page 34 and photo above left.) The second reason is that, thanks to years of dedicated work by The American Chestnut Foundation (www.afc.org), 60 years from now, we may have some mature stands of American chestnut growing in the once-blighted regions of the East. For the last 25 years, they have overseen a breeding program to develop a blight-resistant genetic strain of American chestnut. In fact, last fall they began harvesting nuts that they believe will produce blight resistant tree stock. Due to the slow growth of chestnut trees, the testing phase may last until 2020.1, for one, find that a hopeful and exciting prospect. How Does It Work? While I have never personally had the opportunity to work with chestnut, field editor Chris Marshall reports, "If you've worked with red oak, you have essentially worked with chestnut. It is almost identical in its machining characteristics." Perfect for everything from outdoor furniture to a fine dining room table, American chestnut might be just the ticket for your next project._ Woodworker's Journal June 2008 Castanea dentata Th e native range of American chestnut (Castanea dentata) stretches from Massachusetts to central Mississippi and as far west as Indiana. When Europeans arrived in North America, 25 percent of all trees in the Eastern forests were American chestnut. They commonly stood over 100 feet tall and as much as seven feet in diameter. Chestnut was truly the "Eastern Giant." American chestnut never exceeded one percent of the nation's total hardwood lumber output, but it made up a full 25 percent of lumber sales for the Appalachian region. When cut, the stump would sprout new stems that grew so fast they would quickly overtop red oak, white oak and hickory, reducing the other species to poorly formed understory trees. Tragedy struck in 1904: a blight was noticed around the area of the Bronx Zoo. It had been brought over on Chinese chestnut trees planted at the zoo as ornamentals. American chestnut had no natural resistance to the blight. Chestnut forests began to die en masse. G. F. Gravatt, of the U.S.D.A., in a report to the Society of American Foresters in 1923, stated that in 1913 the infection had not yet reached Virginia. By 1923, all chestnut trees in Virginia had died, and the blight engulfed North Carolina. He proved prophetic in proclaiming, "There is no reason to expect that anything will prevent the death of the remaining chestnut stands." By 1950, 3.5 billion American chestnut stood dead in the eastern United States. The durability of American chestnut wood allowed for the continued harvest of the dead trees for 20 years after their demise. 'Wormy" chestnut became fashionable in paneling and picture frames. To this day, tobacco barns, hay barns, outbuildings, fences and abandoned cabins built of chestnut still stand. Scattered trees of planted American chestnut remain on the Pacific coast and other areas the blight has not yet invaded, but it has been extirpated from its native range. But there is still hope. The blight only killed the above-ground growth of the American chestnut. Stumps and root stocks of trees killed over 100 years ago still sprout, grow to 6" to 14" in diameter, and die back. The persistence of this rootstock is allowing scientists to intensively study ways to breed blight resistance x into the tree. You may .-' ' .; - help that effort by - " . "• supporting the American Chestnut Foundation. - — T. C. Knight, Silviculturist N Jessieville, Arkansas 31 |