Woodworker's Journal Summer-2008, страница 22

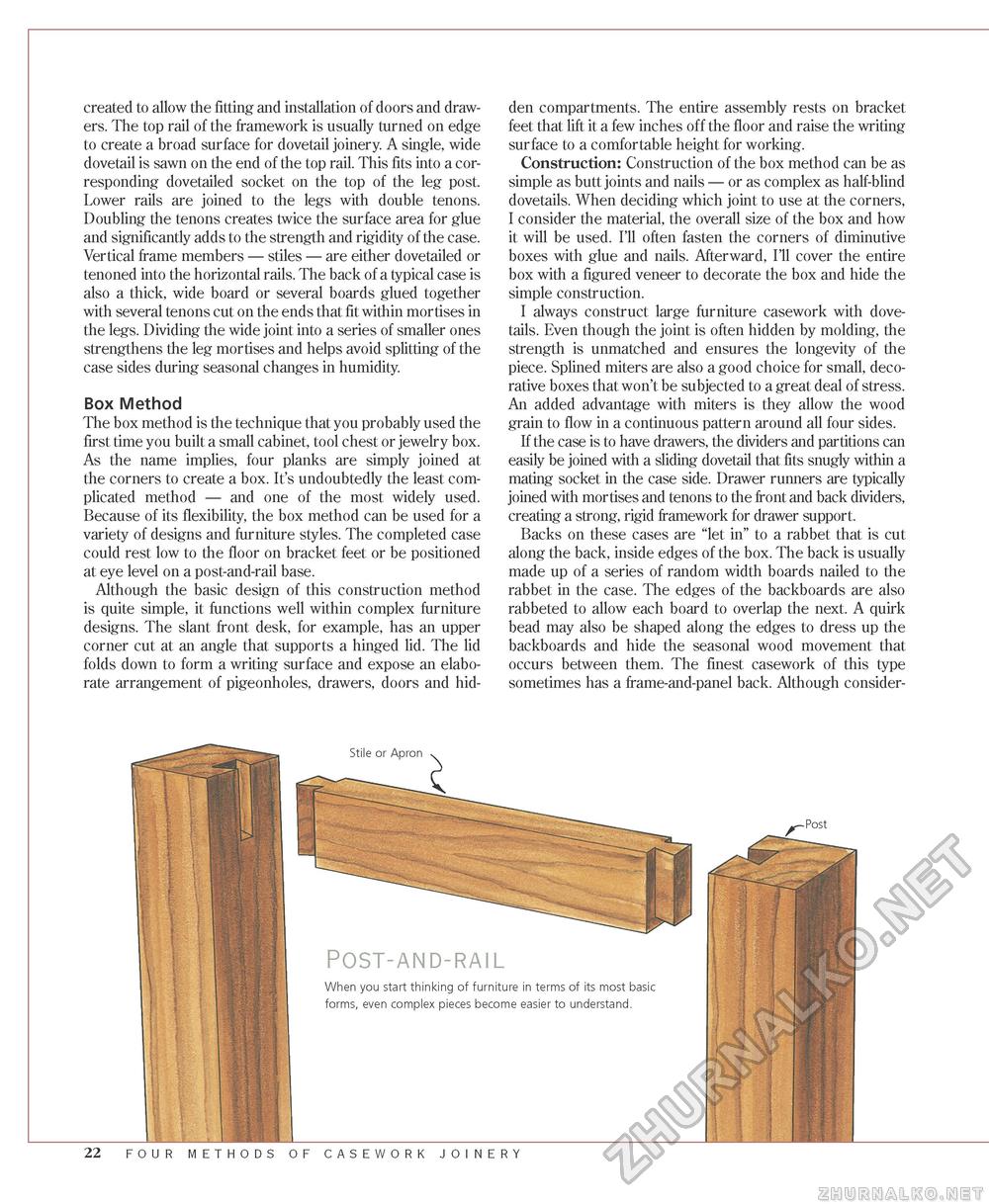

created to allow the fitting and installation of doors and drawers. The top rail of the framework is usually turned on edge to create a broad surface for dovetail joinery. A single, wide dovetail is sawn on the end of the top rail. This fits into a corresponding dovetailed socket on the top of the leg post. Lower rails are joined to the legs with double tenons. Doubling the tenons creates twice the surface area for glue and significantly adds to the strength and rigidity of the case. Vertical frame members — stiles — are either dovetailed or tenoned into the horizontal rails. The back of a typical case is also a thick, wide board or several boards glued together with several tenons cut on the ends that fit within mortises in the legs. Dividing the wide joint into a series of smaller ones strengthens the leg mortises and helps avoid splitting of the case sides during seasonal changes in humidity. Box Method The box method is the technique that you probably used the first time you built a small cabinet, tool chest or jewelry box. As the name implies, four planks are simply joined at the corners to create a box. It's undoubtedly the least complicated method — and one of the most widely used. Because of its flexibility, the box method can be used for a variety of designs and furniture styles. The completed case could rest low to the floor on bracket feet or be positioned at eye level on a post-and-rail base. Although the basic design of this construction method is quite simple, it functions well within complex furniture designs. The slant front desk, for example, has an upper corner cut at an angle that supports a hinged lid. The lid folds down to form a writing surface and expose an elaborate arrangement of pigeonholes, drawers, doors and hid den compartments. The entire assembly rests on bracket feet that lift it a few inches off the floor and raise the writing surface to a comfortable height for working. Construction: Construction of the box method can be as simple as butt joints and nails — or as complex as half-blind dovetails. When deciding which joint to use at the corners, I consider the material, the overall size of the box and how it will be used. I'll often fasten the corners of diminutive boxes with glue and nails. Afterward, I'll cover the entire box with a figured veneer to decorate the box and hide the simple construction. I always construct large furniture casework with dovetails. Even though the joint is often hidden by molding, the strength is unmatched and ensures the longevity of the piece. Splined miters are also a good choice for small, decorative boxes that won't be subjected to a great deal of stress. An added advantage with miters is they allow the wood grain to flow in a continuous pattern around all four sides. If the case is to have drawers, the dividers and partitions can easily be joined with a sliding dovetail that fits snugly within a mating socket in the case side. Drawer runners are typically joined with mortises and tenons to the front and back dividers, creating a strong, rigid framework for drawer support. Backs on these cases are "let in" to a rabbet that is cut along the back, inside edges of the box. The back is usually made up of a series of random width boards nailed to the rabbet in the case. The edges of the backboards are also rabbeted to allow each board to overlap the next. A quirk bead may also be shaped along the edges to dress up the backboards and hide the seasonal wood movement that occurs between them. The finest casework of this type sometimes has a frame-and-panel back. Although consider- 22 four methods of casework joinery |