Popular Woodworking 2003-06 № 134, страница 40

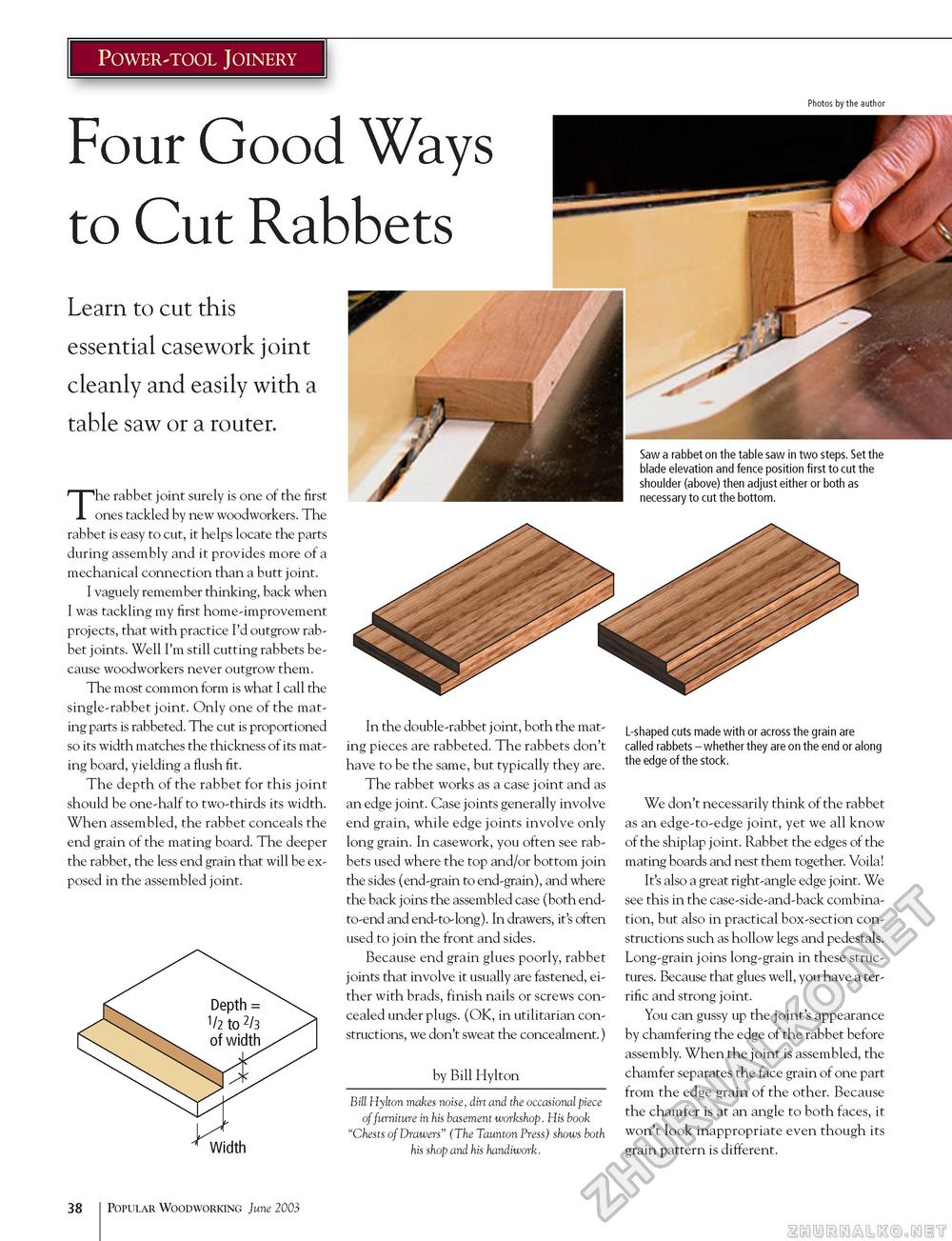

Power-tool Joinery Four Good Ways to Cut Rabbets Learn to cut this essential casework joint cleanly and easily with a table saw or a router. The rabbet joint surely is one of the first ones tackled by new woodworkers. The rabbet is easy to cut, it helps locate the parts during assembly and it provides more of a mechanical connection than a butt joint. I vaguely remember thinking, back when I was tackling my first home-improvement projects, that with practice I'd outgrow rabbet joints. Well I'm still cutting rabbets because woodworkers never outgrow them. The most common form is what I call the single-rabbet joint. Only one of the mating parts is rabbeted. The cut is proportioned so its width matches the thickness of its mating board, yielding a flush fit. The depth of the rabbet for this joint should be one-half to two-thirds its width. When assembled, the rabbet conceals the end grain of the mating board. The deeper the rabbet, the less end grain that will be exposed in the assembled joint. Photos by the author Saw a rabbet on the table saw in two steps. Set the blade elevation and fence position first to cut the shoulder (above) then adjust either or both as necessary to cut the bottom. T Width In the double-rabbet joint, both the mating pieces are rabbeted. The rabbets don't have to be the same, but typically they are. The rabbet works as a case joint and as an edge joint. Case joints generally involve end grain, while edge joints involve only long grain. In casework, you often see rabbets used where the top and/or bottom join the sides (end-grain to end-grain), and where the back joins the assembled case (both end-to-end and end-to-long). In drawers, it's often used to join the front and sides. Because end grain glues poorly, rabbet joints that involve it usually are fastened, either with brads, finish nails or screws concealed under plugs. (OK, in utilitarian constructions, we don't sweat the concealment.) by Bill Hylton Bill Hylton makes noise, dirt and the occasional piece of furniture in his basement workshop. His book "Chests of Drawers" (The Taunton Press) shows both his shop and his handiwork. L-shaped cuts made with or across the grain are called rabbets - whether they are on the end or along the edge of the stock. We don't necessarily think of the rabbet as an edge-to-edge joint, yet we all know of the shiplap joint. Rabbet the edges of the mating boards and nest them together. Voila! It's also a great right-angle edge joint. We see this in the case-side-and-back combination, but also in practical box-section constructions such as hollow legs and pedestals. Long-grain joins long-grain in these structures. Because that glues well, you have a terrific and strong joint. You can gussy up the joint's appearance by chamfering the edge of the rabbet before assembly. When the joint is assembled, the chamfer separates the face grain of one part from the edge grain of the other. Because the chamfer is at an angle to both faces, it won't look inappropriate even though its grain pattern is different. 38 Popular Woodworking June 2003 |