Popular Woodworking 2005-10 № 150, страница 47

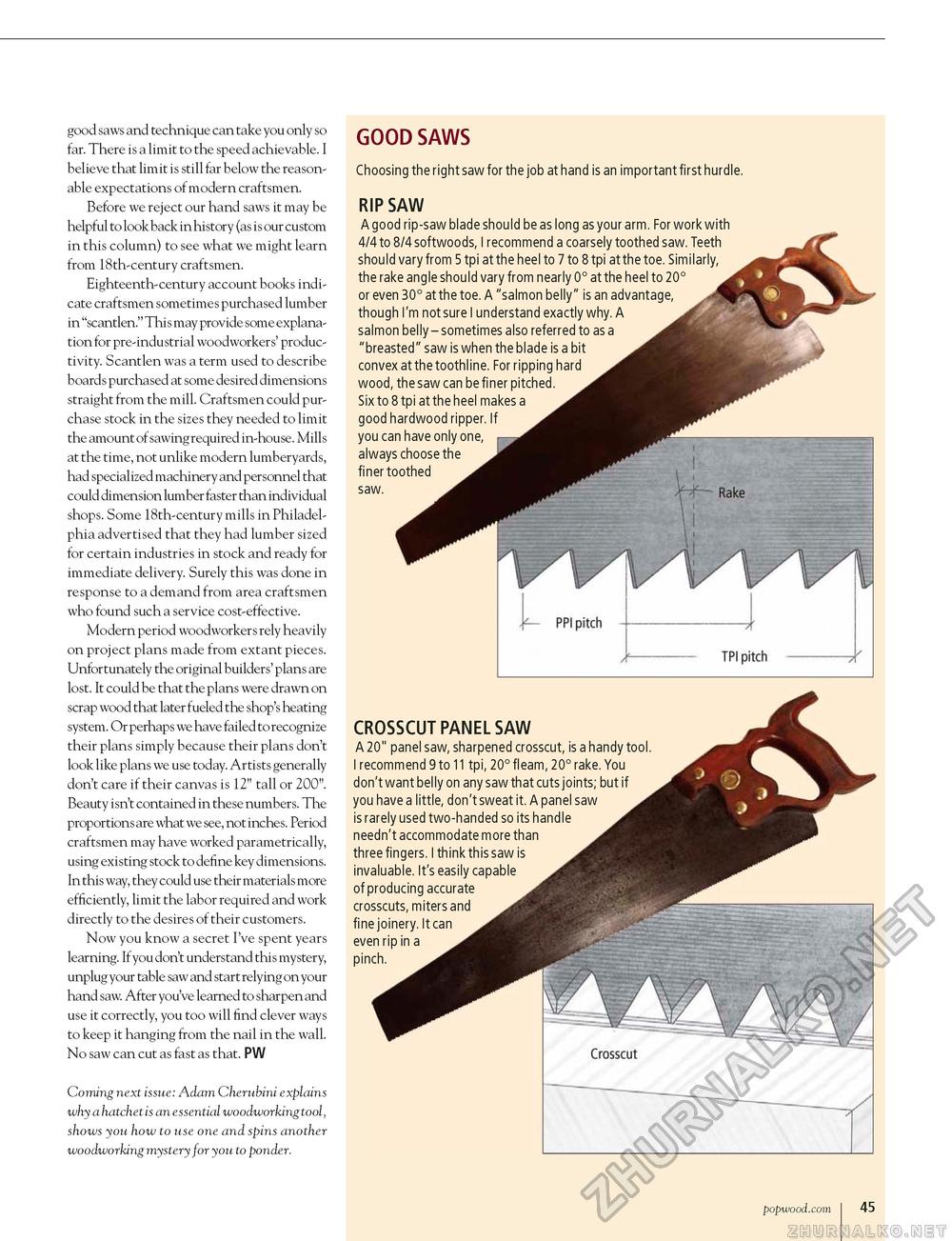

good saws and technique can take you only so far. There is a limit to the speed achievable. I believe that limit is still far below the reasonable expectations of modern craftsmen. Before we reject our hand saws it may be helpful to look back in history (as is our custom in this column) to see what we might learn from 18th-century craftsmen. Eighteenth-century account books indicate craftsmen sometimes purchased lumber in "scantlen." This may provide some explanation for pre-industrial woodworkers' productivity. Scantlen was a term used to describe boards purchased at some desired dimensions straight from the mill. Craftsmen could purchase stock in the sizes they needed to limit the amount of sawing required in-house. Mills at the time, not unlike modern lumberyards, had specialized machinery and personnel that could dimension lumber faster than individual shops. Some 18th-century mills in Philadelphia advertised that they had lumber sized for certain industries in stock and ready for immediate delivery. Surely this was done in response to a demand from area craftsmen who found such a service cost-effective. Modern period woodworkers rely heavily on project plans made from extant pieces. Unfortunately the original builders' plans are lost. It could be that the plans were drawn on scrap wood that later fueled the shop's heating system. Or perhaps we have failed to recognize their plans simply because their plans don't look like plans we use today. Artists generally don't care if their canvas is 12" tall or 200". Beauty isn't contained in these numbers. The proportions are what we see, not inches. Period craftsmen may have worked parametrically, using existing stock to define key dimensions. In this way, they could use their materials more efficiently, limit the labor required and work directly to the desires of their customers. Now you know a secret I've spent years learning. If you don't understand this mystery, unplug your table saw and start relying on your hand saw. After you've learned to sharpen and use it correctly, you too will find clever ways to keep it hanging from the nail in the wall. No saw can cut as fast as that. PW Coming next issue: Adam Cherubini explains why a hatchet is an essential woodworking tool, shows you how to use one and spins another woodworking mystery for you to ponder. GOOD SAWS Choosing the right saw for the job at hand is an important first hurdle. RIP SAW A good rip-saw blade should be as long as your arm. For work with 4/4 to 8/4 softwoods, I recommend a coarsely toothed saw. Teeth should vary from 5 tpi at the heel to 7 to 8 tpi at the toe. Similarly, the rake angle should vary from nearly 0° at the heel to 20° or even 30° at the toe. A "salmon belly" is an advantage, though I'm not sure I understand exactly why. A salmon belly - sometimes also referred to as a "breasted" saw is when the blade is a bit convex at the toothline. For ripping hard wood, the saw can be finer pitched. Six to 8 tpi at the heel makes a good hardwood ripper. If you can have only one, always choose the finer toothed saw. CROSSCUT PANEL SAW A 20" panel saw, sharpened crosscut, is a handy tool. I recommend 9 to 11 tpi, 20° fleam, 20° rake. You don't want belly on any saw that cuts joints; but if you have a little, don't sweat it. A panel saw is rarely used two-handed so its handle needn't accommodate more than three fingers. I think this saw is invaluable. It's easily capable of producing accurate crosscuts, miters and fine joinery. It can even rip in a pinch. popwood.com i 45 |