Popular Woodworking 2005-11 № 151, страница 43

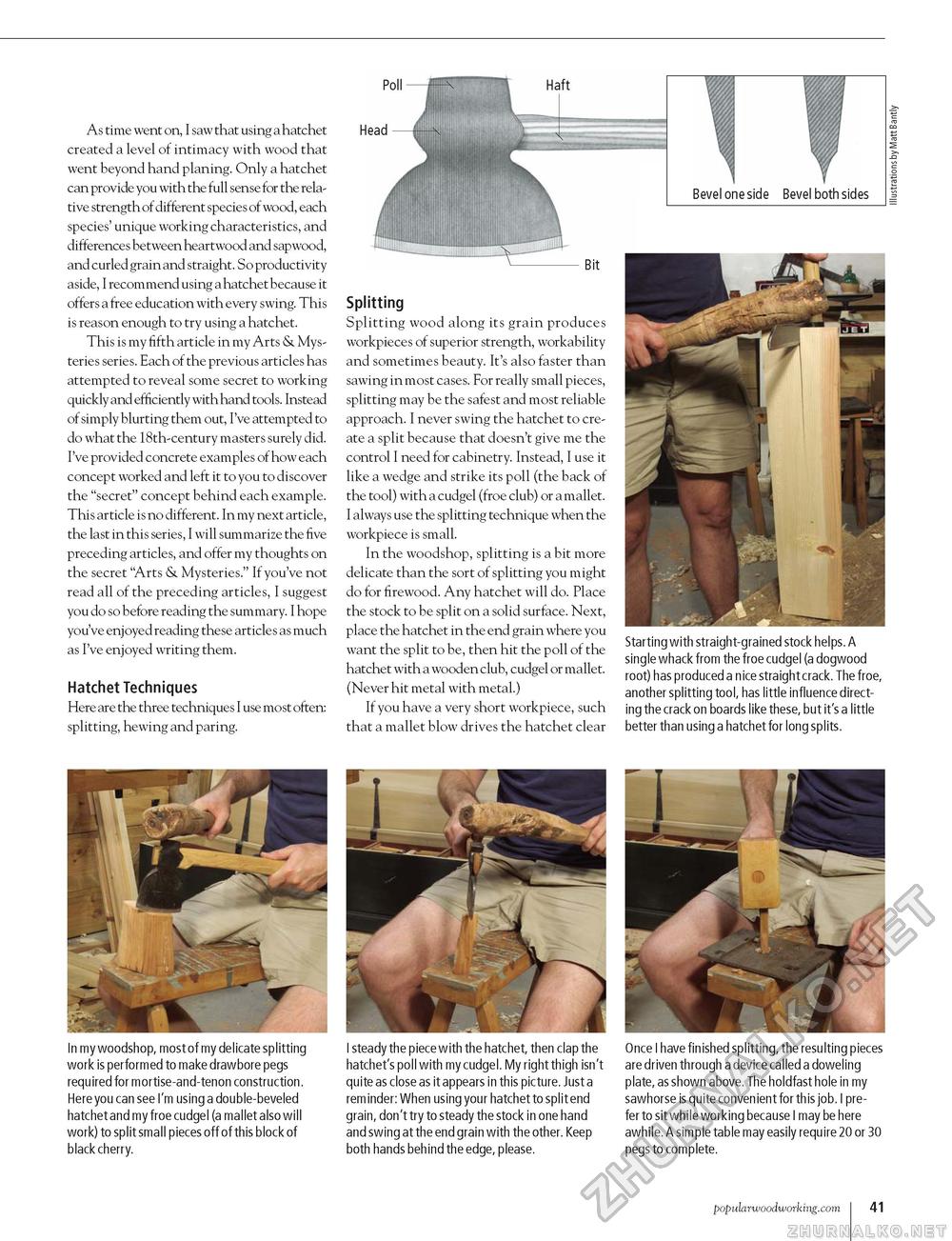

As time went on, I saw that using a hatchet created a level of intimacy with wood that went beyond hand planing. Only a hatchet can provide you with the full sense for the relative strength of different species of wood, each species' unique working characteristics, and differences between heartwood and sap wood, and curled grain and straight. So productivity aside, I recommend using a hatchet because it offers a free education with every swing. This is reason enough to try using a hatchet. This is my fifth article in my Arts & Mysteries series. Each of the previous articles has attempted to reveal some secret to working quickly and efficiently with hand tools. Instead of simply blurting them out, I've attempted to do what the 18th-century masters surely did. I've provided concrete examples of how each concept worked and left it to you to discover the "secret" concept behind each example. This article is no different. In my next article, the last in this series, I will summarize the five preceding articles, and offer my thoughts on the secret "Arts & Mysteries." If you've not read all of the preceding articles, I suggest you do so before reading the summary. I hope you've enjoyed reading these articles as much as I've enjoyed writing them. Hatchet Techniques Here are the three techniques I use most often: splitting, hewing and paring. Head —tr Bit Splitting Splitting wood along its grain produces workpieces of superior strength, workability and sometimes beauty. It's also faster than sawing in most cases. For really small pieces, splitting may be the safest and most reliable approach. I never swing the hatchet to create a split because that doesn't give me the control I need for cabinetry. Instead, I use it like a wedge and strike its poll (the back of the tool) with a cudgel (froe club) or a mallet. I always use the splitting technique when the workpiece is small. In the woodshop, splitting is a bit more delicate than the sort of splitting you might do for firewood. Any hatchet will do. Place the stock to be split on a solid surface. Next, place the hatchet in the end grain where you want the split to be, then hit the poll of the hatchet with a wooden club, cudgel or mallet. (Never hit metal with metal.) If you have a very short workpiece, such that a mallet blow drives the hatchet clear Starting with straight-grained stock helps. A single whack from the froe cudgel (a dogwood root) has produced a nice straight crack. The froe, another splitting tool, has little influence directing the crack on boards like these, but it's a little better than using a hatchet for long splits. n my woodshop, most of my delicate splitting work is performed to make drawbore pegs required for mortise-and-tenon construction. Here you can see I'm using a double-beveled hatchet and my froe cudgel (a mallet also will work) to split small pieces off of this block of black cherry. I steady the piece with the hatchet, then clap the hatchet's poll with my cudgel. My right thigh isn't quite as close as it appears in this picture. Just a reminder: When using your hatchet to split end grain, don't try to steady the stock in one hand and swing at the end grain with the other. Keep both hands behind the edge, please. Once I have finished splitting, the resulting pieces are driven through a device called a doweling plate, as shown above. The holdfast hole in my sawhorse is quite convenient for this job. I prefer to sit while working because I may be here awhile. A simple table may easily require 20 or 30 pegs to complete. popularwoodworking.com 41 |