Popular Woodworking 2005-11 № 151, страница 44

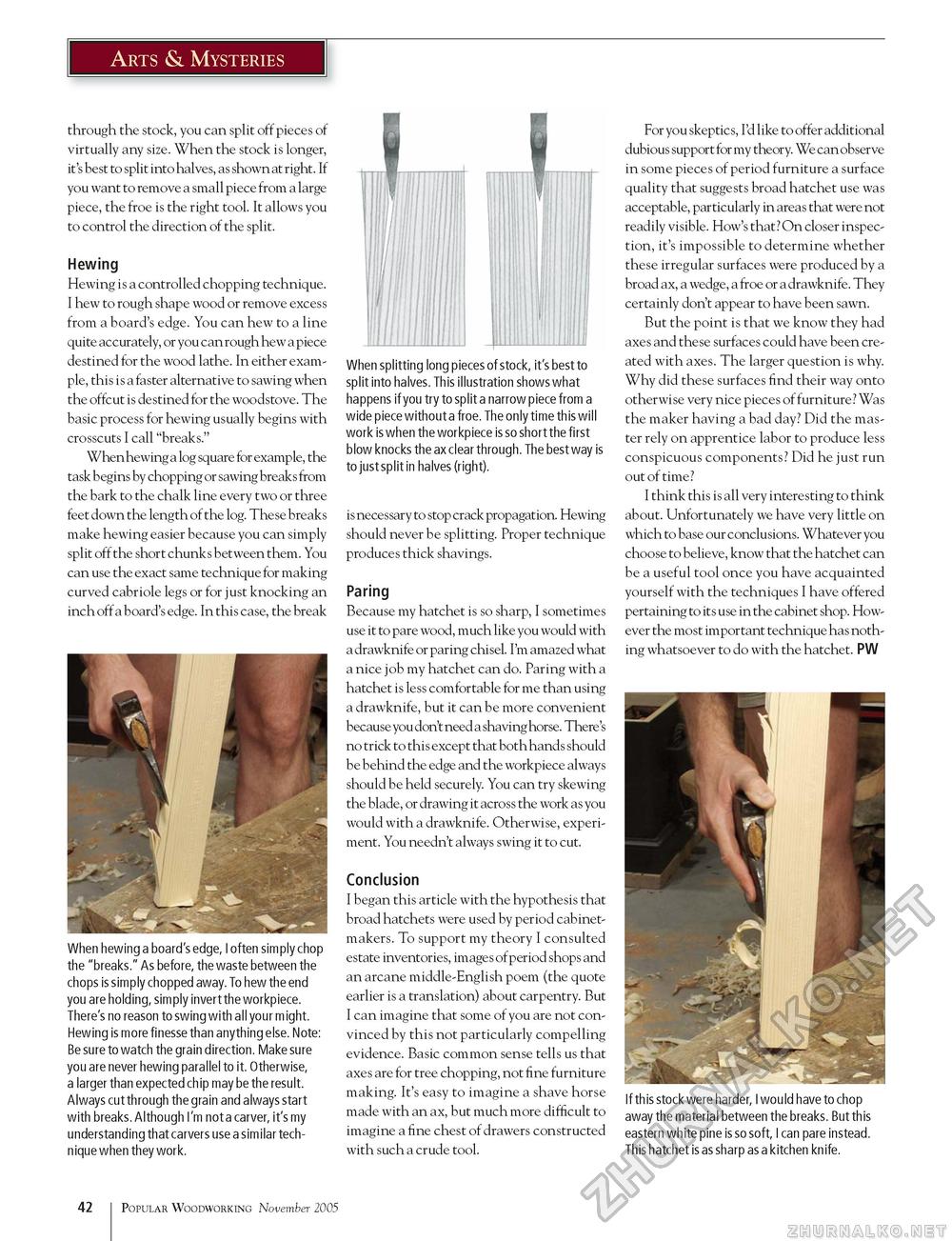

Arts & Mysteries through the stock, you can split off pieces of virtually any size. When the stock is longer, it's best to split into halves, as shown at right. If you want to remove a small piece from a large piece, the froe is the right tool. It allows you to control the direction of the split. Hewing Hewing is a controlled chopping technique. I hew to rough shape wood or remove excess from a board's edge. You can hew to a line quite accurately, or you can rough hew a piece destined for the wood lathe. In either example, this is a faster alternative to sawing when the offcut is destined for the woodstove. The basic process for hewing usually begins with crosscuts I call "breaks." When hewing a log square for example, the task begins by chopping or sawing breaks from the bark to the chalk line every two or three feet down the length of the log. These breaks make hewing easier because you can simply split off the short chunks between them. You can use the exact same technique for making curved cabriole legs or for just knocking an inch off a board's edge. In this case, the break When hewing a board's edge, I often simply chop the "breaks." As before, the waste between the chops is simply chopped away. To hew the end you are holding, simply invert the workpiece. There's no reason to swing with all your might. Hewing is more finesse than anything else. Note: Be sure to watch the grain direction. Make sure you are never hewing parallel to it. Otherwise, a larger than expected chip may be the result. Always cut through the grain and always start with breaks. Although I'm not a carver, it's my understanding that carvers use a similar technique when they work. When splitting long pieces of stock, it's best to split into halves. This illustration shows what happens if you try to split a narrow piece from a wide piece without a froe. The only time this will work is when the workpiece is so short the first blow knocks the ax clear through. The best way is to just split in halves (right). is necessary to stop crack propagation. Hewing should never be splitting. Proper technique produces thick shavings. Paring Because my hatchet is so sharp, I sometimes use it to pare wood, much like you would with a drawknife or paring chisel. I'm amazed what a nice job my hatchet can do. Paring with a hatchet is less comfortable for me than using a drawknife, but it can be more convenient because you don't need a shaving horse. There's no trick to this except that both hands should be behind the edge and the workpiece always should be held securely. You can try skewing the blade, or drawing it across the work as you would with a drawknife. Otherwise, experiment. You needn't always swing it to cut. Conclusion I began this article with the hypothesis that broad hatchets were used by period cabinetmakers. To support my theory I consulted estate inventories, images ofperiod shops and an arcane middle-English poem (the quote earlier is a translation) about carpentry. But I can imagine that some of you are not convinced by this not particularly compelling evidence. Basic common sense tells us that axes are for tree chopping, not fine furniture making. It's easy to imagine a shave horse made with an ax, but much more difficult to imagine a fine chest of drawers constructed with such a crude tool. For you skeptics, I'd like to offer additional dubious support for my theory. We can observe in some pieces of period furniture a surface quality that suggests broad hatchet use was acceptable, particularly in areas that were not readily visible. How's that? On closer inspection, it's impossible to determine whether these irregular surfaces were produced by a broad ax, a wedge, a froe or a drawknife. They certainly don't appear to have been sawn. But the point is that we know they had axes and these surfaces could have been created with axes. The larger question is why. Why did these surfaces find their way onto otherwise very nice pieces of furniture? Was the maker having a bad day? Did the master rely on apprentice labor to produce less conspicuous components? Did he just run out of time? I think this is all very interesting to think about. Unfortunately we have very little on which to base our conclusions. Whatever you choose to believe, know that the hatchet can be a useful tool once you have acquainted yourself with the techniques I have offered pertaining to its use in the cabinet shop. However the most important technique has nothing whatsoever to do with the hatchet. PW If this stock were harder, I would have to chop away the material between the breaks. But this eastern white pine is so soft, I can pare instead. This hatchet is as sharp as a kitchen knife. 42 Popular Woodworking November 2005 |