Popular Woodworking 2007-06 № 162, страница 29

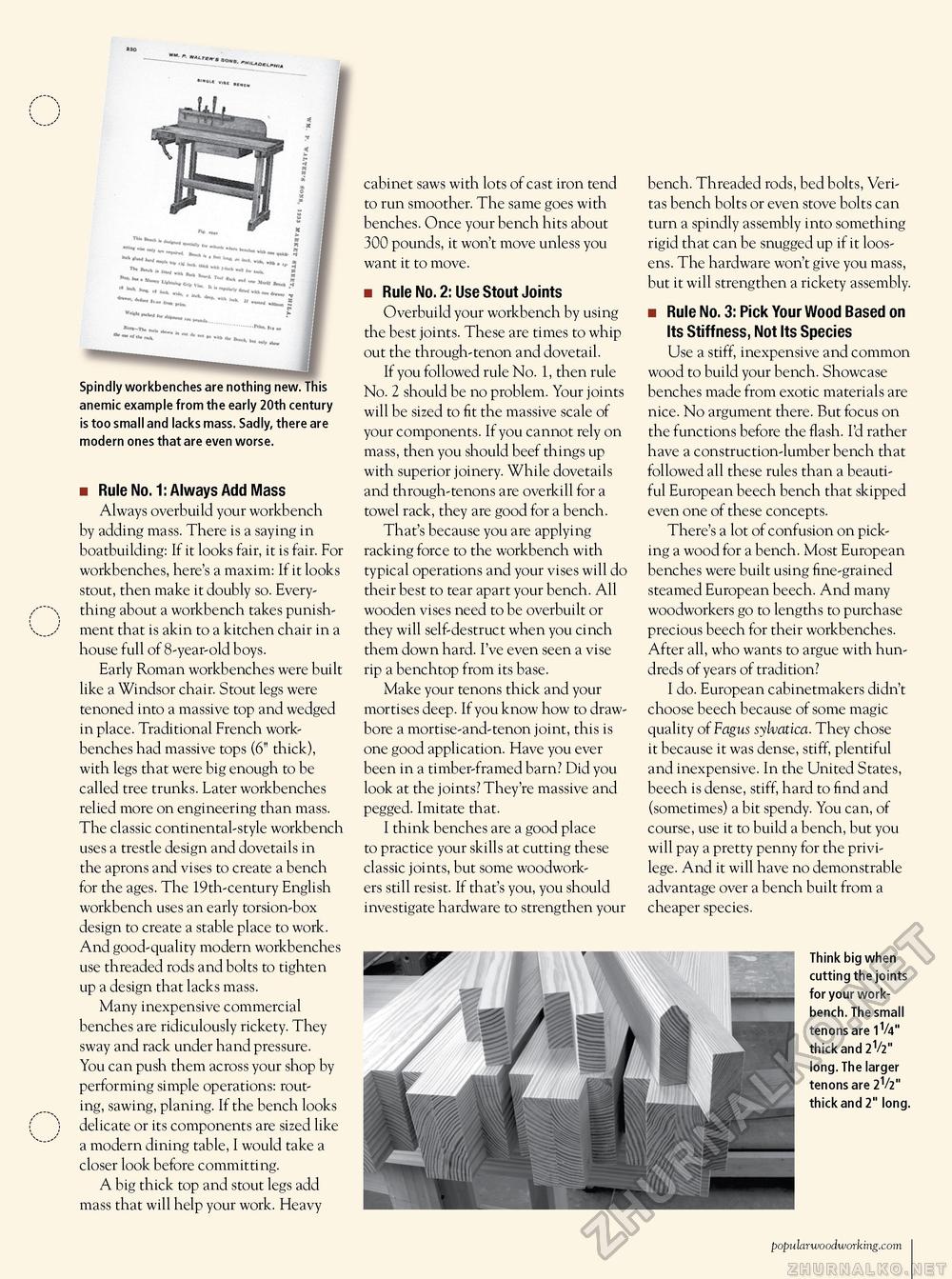

Spindly workbenches are nothing new. This anemic example from the early 20th century is too small and lacks mass. Sadly, there are modern ones that are even worse. ■ Rule No. 1: Always Add Mass Always overbuild your workbench by adding mass. There is a saying in boatbuilding: If it looks fair, it is fair. For workbenches, here's a maxim: If it looks stout, then make it doubly so. Everything about a workbench takes punishment that is akin to a kitchen chair in a house full of 8-year-old boys. Early Roman workbenches were built like a Windsor chair. Stout legs were tenoned into a massive top and wedged in place. Traditional French workbenches had massive tops (6" thick), with legs that were big enough to be called tree trunks. Later workbenches relied more on engineering than mass. The classic continental-style workbench uses a trestle design and dovetails in the aprons and vises to create a bench for the ages. The 19th-century English workbench uses an early torsion-box design to create a stable place to work. And good-quality modern workbenches use threaded rods and bolts to tighten up a design that lacks mass. Many inexpensive commercial benches are ridiculously rickety. They sway and rack under hand pressure. You can push them across your shop by performing simple operations: routing, sawing, planing. If the bench looks delicate or its components are sized like a modern dining table, I would take a closer look before committing. A big thick top and stout legs add mass that will help your work. Heavy cabinet saws with lots of cast iron tend to run smoother. The same goes with benches. Once your bench hits about 300 pounds, it won't move unless you want it to move. ■ Rule No. 2: Use Stout Joints Overbuild your workbench by using the best joints. These are times to whip out the through-tenon and dovetail. If you followed rule No. 1, then rule No. 2 should be no problem. Your joints will be sized to fit the massive scale of your components. If you cannot rely on mass, then you should beef things up with superior joinery. While dovetails and through-tenons are overkill for a towel rack, they are good for a bench. That's because you are applying racking force to the workbench with typical operations and your vises will do their best to tear apart your bench. All wooden vises need to be overbuilt or they will self-destruct when you cinch them down hard. I've even seen a vise rip a benchtop from its base. Make your tenons thick and your mortises deep. If you know how to draw-bore a mortise-and-tenon joint, this is one good application. Have you ever been in a timber-framed barn? Did you look at the joints? They're massive and pegged. Imitate that. I think benches are a good place to practice your skills at cutting these classic joints, but some woodworkers still resist. If that's you, you should investigate hardware to strengthen your bench. Threaded rods, bed bolts, Veri-tas bench bolts or even stove bolts can turn a spindly assembly into something rigid that can be snugged up if it loosens. The hardware won't give you mass, but it will strengthen a rickety assembly. ■ Rule No. 3: Pick Your Wood Based on Its Stiffness, Not Its Species Use a stiff, inexpensive and common wood to build your bench. Showcase benches made from exotic materials are nice. No argument there. But focus on the functions before the flash. I'd rather have a construction-lumber bench that followed all these rules than a beautiful European beech bench that skipped even one of these concepts. There's a lot of confusion on picking a wood for a bench. Most European benches were built using fine-grained steamed European beech. And many woodworkers go to lengths to purchase precious beech for their workbenches. After all, who wants to argue with hundreds of years of tradition? I do. European cabinetmakers didn't choose beech because of some magic quality of Fagus sylvatica. They chose it because it was dense, stiff, plentiful and inexpensive. In the United States, beech is dense, stiff, hard to find and (sometimes) a bit spendy. You can, of course, use it to build a bench, but you will pay a pretty penny for the privilege. And it will have no demonstrable advantage over a bench built from a cheaper species. Think big when cutting the joints for your workbench. The small tenons are 11/4" thick and 2V2" long. The larger tenons are 2V2" thick and 2" long. popularwoodworking.com 23 |