Popular Woodworking 2007-08 № 163, страница 72

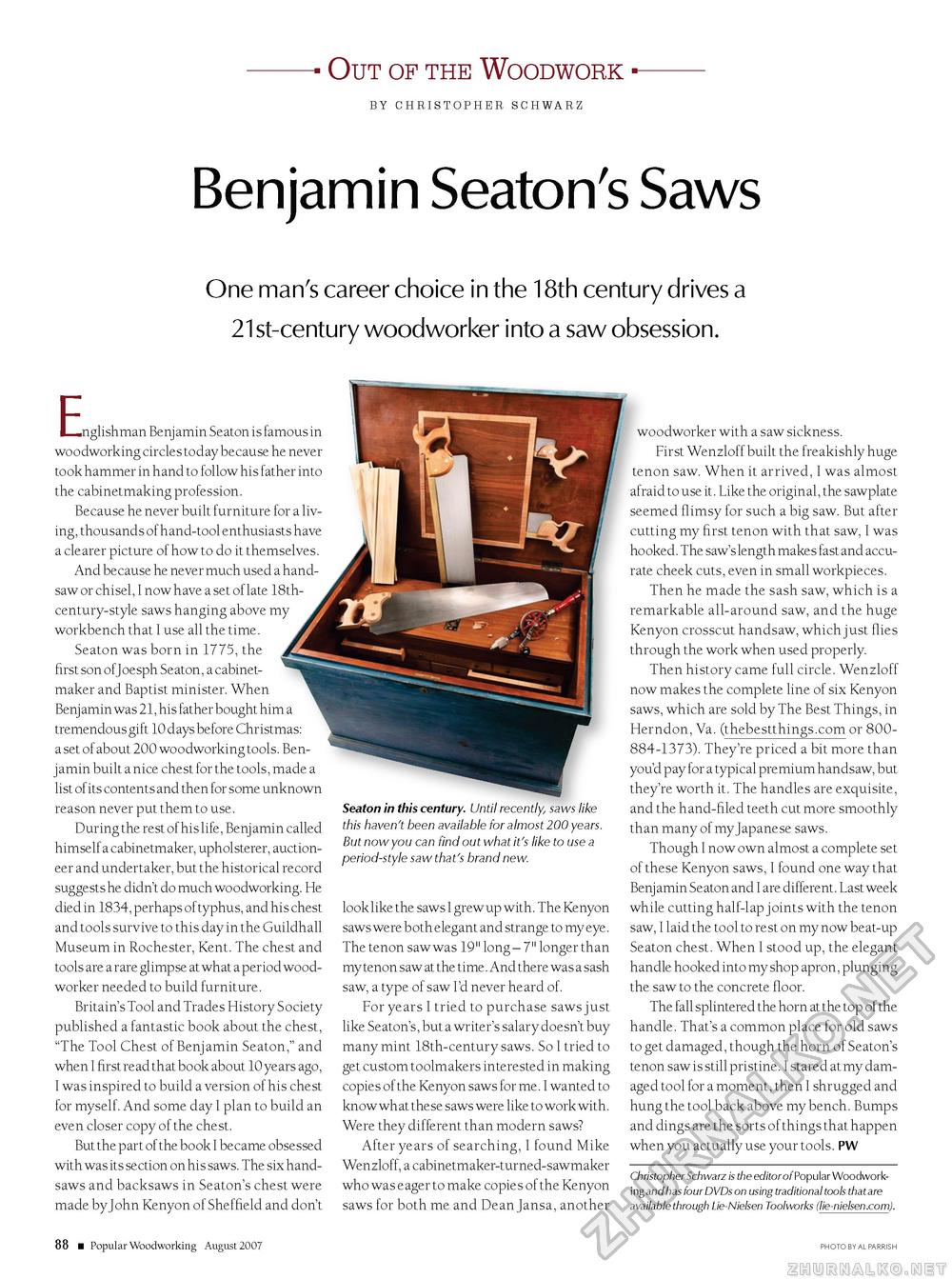

Out of the Woodwork by Christopher schwa rz Benjamin Seaton's Saws One man's career choice in the 18th century drives a 21 st-century woodworker into a saw obsession. E nglishman Benjamin Seaton is famous in woodworking circles today because he never took hammer in hand to follow his father into the cabinetmaking profession. Because he never built furniture for a living, thousands of hand-tool enthusiasts have a cle arer picture of how to do it themselves. And because he never much used a handsaw or chisel, I now have a set of late 18th-century-style saws hanging above my workbench that I use all the time. Seaton was born in 1775, the first son ofJoesph Seaton, a cabinetmaker and Baptist minister. When Benj amin was 21, his father bought him a tremendous gift 10 days before Christmas: a set of about 200 woodworking tools. Benjamin built a nice chest for the tools, made a list of its contents and then for some unknown reason never put them to use. During the rest of his life, Benj amin called himself a cabinetmaker, upholsterer, auctioneer and undertaker, but the historical record suggests he didn't do much woodworking. He died in 1834, perhaps of typhus, and his chest and tools survive to this day in the Guildhall Museum in Rochester, Kent. The chest and tools are a rare glimpse at what a period woodworker needed to build furniture. Britain's Tool and Trades History Society published a fantastic book about the chest, "The Tool Chest of Benjamin Seaton," and when I first read that book about 10 years ago, I was inspired to build a version of his chest for myself. And some day I plan to build an even closer copy of the chest. But the part of the book I became obsessed with was its section on his saws. The six handsaws and backsaws in Seaton's chest were made byJohn Kenyon of Sheffield and don't Seaton in this century. Until recently, saws like this haven't been available for almost 200 years. But now you can find out what it's like to use a period-style saw that's brand new. look like the saws I grew up with. The Kenyon saws were both elegant and strange to my eye. The tenon saw was 19" long - 7" longer than my tenon saw at the time. And there was a sash saw, a type of saw I'd never heard of. For years I tried to purchase saws just like Seaton's, but a writer's salary doesn't buy many mint 18th-century saws. So I tried to get custom toolmakers interested in making copies of the Kenyon saws for me. I wanted to know what these saws were like to work with. Were they different than modern saws? After years of searching, I found Mike Wenzloff, a cabinetmaker-turned-sawmaker who was eager to make copies of the Kenyon saws for both me and Dean Jansa, another woodworker with a saw sickness. First Wenzloff built the freakishly huge tenon saw. When it arrived, I was almost afraid to use it. Like the original, the sawplate seemed flimsy for such a big saw. But after cutting my first tenon with that saw, I was hooked. The saw's length makes fast and accurate cheek cuts, even in small workpieces. Then he made the sash saw, which is a remarkable all-around saw, and the huge Kenyon crosscut handsaw, which just flies through the work when used properly. Then history came full circle. Wenzloff now makes the complete line of six Kenyon saws, which are sold by The Best Things, in Herndon, Va. (thebestthings.com or 800884-1373). They're priced a bit more than you'd pay for a typical premium handsaw, but they're worth it. The handles are exquisite, and the hand-filed teeth cut more smoothly than many of my Japanese saws. Though I now own almost a complete set of these Kenyon saws, I found one way that Benjamin Seaton and I are different. Last week while cutting half-lap joints with the tenon saw, I laid the tool to rest on my now beat-up Seaton chest. When I stood up, the elegant handle hooked into my shop apron, plunging the saw to the concrete floor. The fall splintered the horn at the top of the handle. That's a common place for old saws to get damaged, though the horn of Seaton's tenon saw is still pristine. I stared at my damaged tool for a moment, then I shrugged and hung the tool back above my bench. Bumps and dings are the sorts of things that happen when you actually use your tools. PW Christopher Schwarz is the editor of popular Woodworking and has four DVDs on using traditional tools that are available through Lie-Nielsen Toolworks (lie-nielsen.com). 88 ■ Popular Woodworking August 2007 photo by al parrish |