Popular Woodworking 2008-04 № 168, страница 29

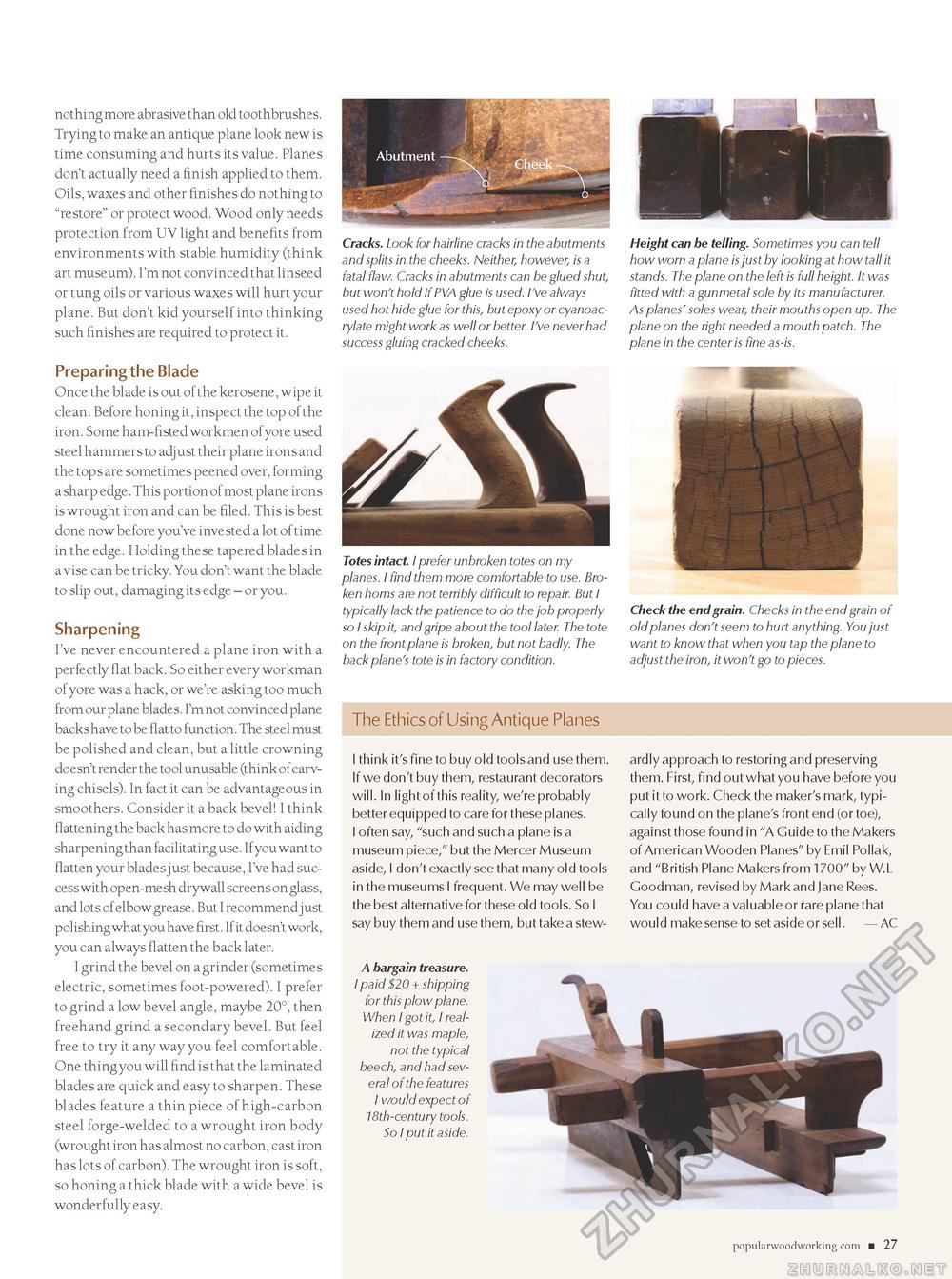

nothing more abrasive than old toothbrushes. Trying to make an antique plane look new is time consuming and hurts its value. Planes don't actually need a finish applied to them. Oils, waxes and other finishes do nothing to "restore" or protect wood. Wood only needs protection from UV light and benefits from environments with stable humidity (think art museum). I'm not convinced that linseed or tung oils or various waxes will hurt your plane. But don't kid yourself into thinking such finishes are required to protect it. Preparing the Blade Once the blade is out of the kerosene, wipe it clean. Before honing it, inspect the top of the iron. Some ham-fisted workmen of yore used steel hammers to adjust their plane irons and the tops are sometimes peened over, forming a sharp edge. This portion of most plane irons is wrought iron and can be filed. This is best done now before you've invested a lot of time in the edge. Holding these tapered blades in a vise can be tricky. You don't want the blade to slip out, damaging its edge - or you. Sharpening I've never encountered a plane iron with a perfectly flat back. So either every workman of yore was a hack, or we're asking too much from our plane blades. I'm not convinced plane backs have to be flat to function. The steel must be polished and clean, but a little crowning doesn't render the tool unusable (think of carving chisels). In fact it can be advantageous in smoothers. Consider it a back bevel! I think flattening the back has more to do with aiding sharpening than facilitating use. If you want to flatten your blades just because, I've had success with open-mesh drywall screens on glass, and lots of elbow grease. But I recommend just polishing what you have first. If it doesn't work, you can always flatten the back later. I grind the bevel on a grinder (sometimes electric, sometimes foot-powered). I prefer to grind a low bevel angle, maybe 20°, then freehand grind a secondary bevel. But feel free to try it any way you feel comfortable. One thing you will find is that the laminated blades are quick and easy to sharpen. These blades feature a thin piece of high-carbon steel forge-welded to a wrought iron body (wrought iron has almost no carbon, cast iron has lots of carbon). The wrought iron is soft, so honing a thick blade with a wide bevel is wonderfully easy. Cracks. Look for hairline cracks in the abutments and splits in the cheeks. Neither, however, is a fatal flaw. Cracks in abutments can be glued shut, but won't hold if PVA glue is used. I've always used hot hide glue for this, but epoxy or cyanoac-rylate might work as well or better. I've never had success gluing cracked cheeks. Totes intact. I prefer unbroken totes on my planes. I find them more comfortable to use. Broken horns are not terribly difficult to repair. But I typically lack the patience to do the job properly so I skip it, and gripe about the tool later. The tote on the front plane is broken, but not badly. The back plane's tote is in factory condition. Height can be telling. Sometimes you can tell how worn a plane is just by looking at how tall it stands. The plane on the left is full height. It was fitted with a gunmetal sole by its manufacturer. As planes' soles wear, their mouths open up. The plane on the right needed a mouth patch. The plane in the center is fine as-is. Check the end grain. Checks in the end grain of old planes don't seem to hurt anything. You just want to know that when you tap the plane to adjust the iron, it won't go to pieces. The Ethics of Using Antique Planes I think it's fine to buy old tools and use them. If we don't buy them, restaurant decorators will. In light of this reality, we're probably better equipped to care for these planes. I often say, "such and such a plane is a museum piece," but the Mercer Museum aside, I don't exactly see that many old tools in the museums I frequent. We may well be the best alternative for these old tools. So I say buy them and use them, but take a stew- ardly approach to restoring and preserving them. First, find out what you have before you put it to work. Check the maker's mark, typically found on the plane's front end (or toe), against those found in "A Guide to the Makers of American Wooden Planes" by Emil Pollak, and "British Plane Makers from 1700" by W.L Goodman, revised by Mark and Jane Rees. You could have a valuable or rare plane that would make sense to set aside or sell. — AC A bargain treasure. I paid $20 + shipping for this plow plane. When I got it, I realized it was maple, not the typical beech, and had several of the features I would expect of 18th-century tools. So I put it aside. popularwoodworking.com ■ 27 CIRCLE #100 ON FREE INFORMATION CARD. |