Popular Woodworking 2009-11 № 179, страница 12

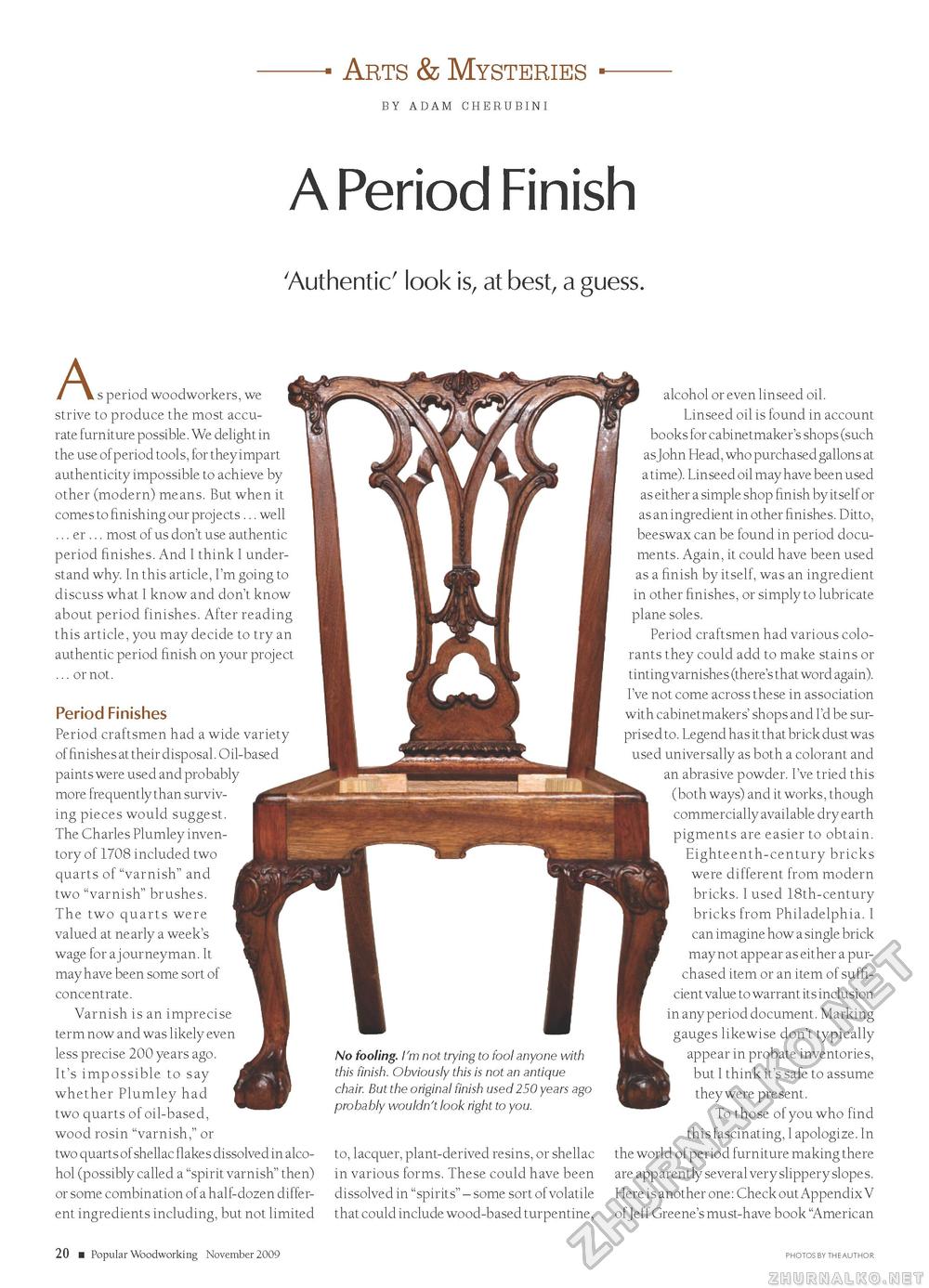

Arts & Mysteries BY ADAM CHERUBINI A Period Finish 'Authentic' look is, at best, a guess. A s k s period woodworkers, we strive to produce the most accurate furniture possible. We delight in the use of period tools, for they impart authenticity impossible to achieve by other (modern) means. But when it comes to finishing our projects ... well ... er ... most of us don't use authentic period finishes. And I think I understand why. In this article, I'm going to discuss what I know and don't know about period finishes. After reading this article, you may decide to try an authentic period finish on your project ... or not. Period Finishes Period craftsmen had a wide variety of finishes at their disposal. Oil-based paints were used and probably more frequently than surviving pieces would suggest. The Charles Plumley inventory of 1708 included two quarts of "varnish" and two "varnish" brushes. The two quarts were valued at nearly a week's wage for a journeyman. It may have been some sort of concentrate. Varnish is an imprecise term now and was likely even less precise 200 years ago. It's impossible to say whether Plumley had two quarts of oil-based, wood rosin "varnish," or two quarts of shellac flakes dissolved in alcohol (possibly called a "spirit varnish" then) or some combination of a half-dozen different ingredients including, but not limited to, lacquer, plant-derived resins, or shellac in various forms. These could have been dissolved in "spirits" - some sort of volatile that could include wood-based turpentine, alcohol or even linseed oil. Linseed oil is found in account books for cabinetmaker's shops (such asJohn Head, who purchased gallons at a time). Linseed oil may have been used as either a simple shop finish by itself or as an ingredient in other finishes. Ditto, beeswax can be found in period documents. Again, it could have been used as a finish by itself, was an ingredient in other finishes, or simply to lubricate plane soles. Period craftsmen had various colorants they could add to make stains or tinting varnishes (there's that word again). 've not come across these in association with cabinetmakers' shops and I'd be surprised to. Legend has it that brick dust was used universally as both a colorant and an abrasive powder. I've tried this (both ways) and it works, though commercially available dry earth pigments are easier to obtain. Eighteenth-century bricks were different from modern bricks. I used 18th-century bricks from Philadelphia. I can imagine how a single brick may not appe ar as either a purchased item or an item of sufficient value to warrant its inclusion in any period document. Marking gauges likewise don't typically appear in probate inventories, but I think it's safe to assume they were present. To those of you who find this fascinating, I apologize. In the world of period furniture making there are apparently several very slippery slopes. Here is another one: Check out Appendix V of Jeff Greene's must-have book "American 20 ■ Popular Woodworking November 2009 PHOTOS BY THEAUTHOR |