Woodworker's Journal 1985-9-4, страница 25

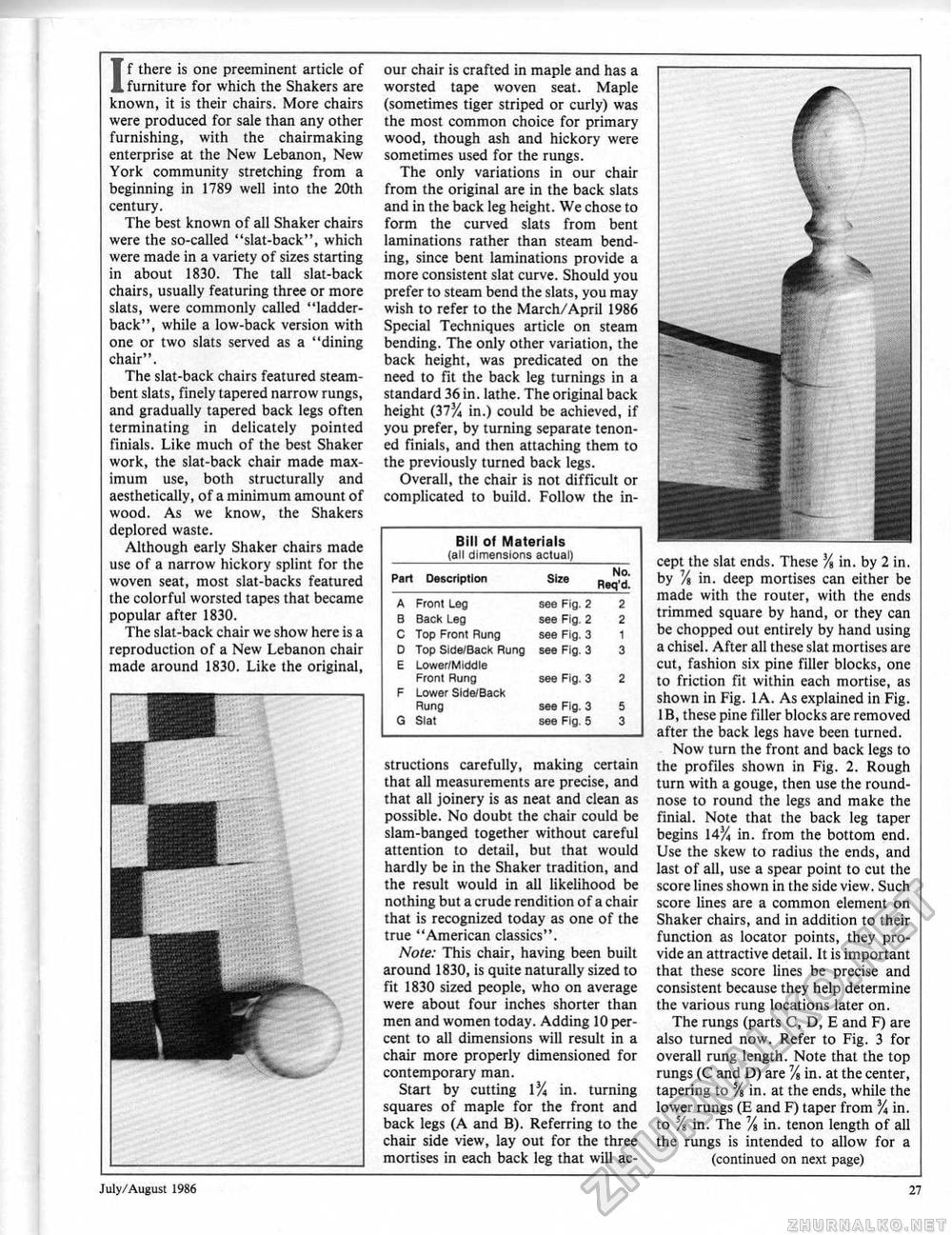

If there is one preeminent article of furniture for which the Shakers are known, it is their chairs. More chairs were produced for sale than any other furnishing, with the chairmaking enterprise at the New Lebanon, New York community stretching from a beginning in 1789 well into the 20th century. The best known of all Shaker chairs were the so-called "slat-back", which were made in a variety of sizes starting in about 1830. The tall slat-back chairs, usually featuring three or more slats, were commonly called "ladder-back", while a low-back version with one or two slats served as a "dining chair". The slat-back chairs featured steam-bent slats, finely tapered narrow rungs, and gradually tapered back legs often terminating in delicately pointed finials. Like much of the best Shaker work, the slat-back chair made maximum use, both structurally and aesthetically, of a minimum amount of wood. As we know, the Shakers deplored waste. Although early Shaker chairs made use of a narrow hickory splint for the woven seat, most slat-backs featured the colorful worsted tapes that became popular after 1830. The slat-back chair we show here is a reproduction of a New Lebanon chair made around 1830. Like the original, our chair is crafted in maple and has a worsted tape woven seat. Maple (sometimes tiger striped or curly) was the most common choice for primary wood, though ash and hickory were sometimes used for the rungs. The only variations in our chair from the original are in the back slats and in the back leg height. We chose to form the curved slats from bent laminations rather than steam bending, since bent laminations provide a more consistent slat curve. Should you prefer to steam bend the slats, you may wish to refer to the March/April 1986 Special Techniques article on steam bending. The only other variation, the back height, was predicated on the need to fit the back leg turnings in a standard 36 in. iathe. The original back height (37% in.) could be achieved, if you prefer, by turning separate tenoned finials, and then attaching them to the previously turned back legs. Overall, the chair is not difficult or complicated to build. Follow the in- Bill of Materials (all dimensions actual) Bill of Materials (all dimensions actual)

structions carefully, making certain that all measurements are precise, and that all joinery is as neat and clean as possible. No doubt the chair could be slam-banged together without careful attention to detail, but that would hardly be in the Shaker tradition, and the result would in all likelihood be nothing but a crude rendition of a chair that is recognized today as one of the true "American classics". Note: This chair, having been built around 1830, is quite naturally sized to fit 1830 sized people, who on average were about four inches shorter than men and women today. Adding 10 percent to ail dimensions will result in a chair more properly dimensioned for contemporary man. Start by cutting 1% in. turning squares of maple for the front and back legs (A and B). Referring to the chair side view, lay out for the three mortises in each back leg that will ac cept the slat ends, These % in. by 2 in. by Vi in. deep mortises can either be made with the router, with the ends trimmed square by hand, or they can be chopped out entirely by hand using a chisel. After all these slat mortises are cut, fashion six pine filler blocks, one to friction fit within each mortise, as shown in Fig. I A. As explained in Fig. IB, these pine filler blocks are removed after the back legs have been turned. Now turn the front and back legs to the profiles shown in Fig. 2. Rough turn with a gouge, then use the round-nose to round the legs and make the finial. Note that the back leg taper begins 14% in, from the bottom end. Use the skew to radius the ends, and last of all, use a spear point to cut the score lines shown in the side view. Such score lines are a common element on Shaker chairs, and in addition to their function as locator points, they provide an attractive detail, it is important that these score lines be precise and consistent because they help determine the various rung locations later on. The rungs (parts C, D, E and F) are also turned now. Refer to Fig. 3 for overall rung length. Note that the top rungs (C and D) are % in. at the center, tapering to % in. at the ends, while the iower rungs (E and F) taper from % in. to SA in. The % in. tenon length of all the rungs is intended to allow for a (continued on next page) J uly/August 1986 27 |