Woodworker's Journal 1994-18-5, страница 27

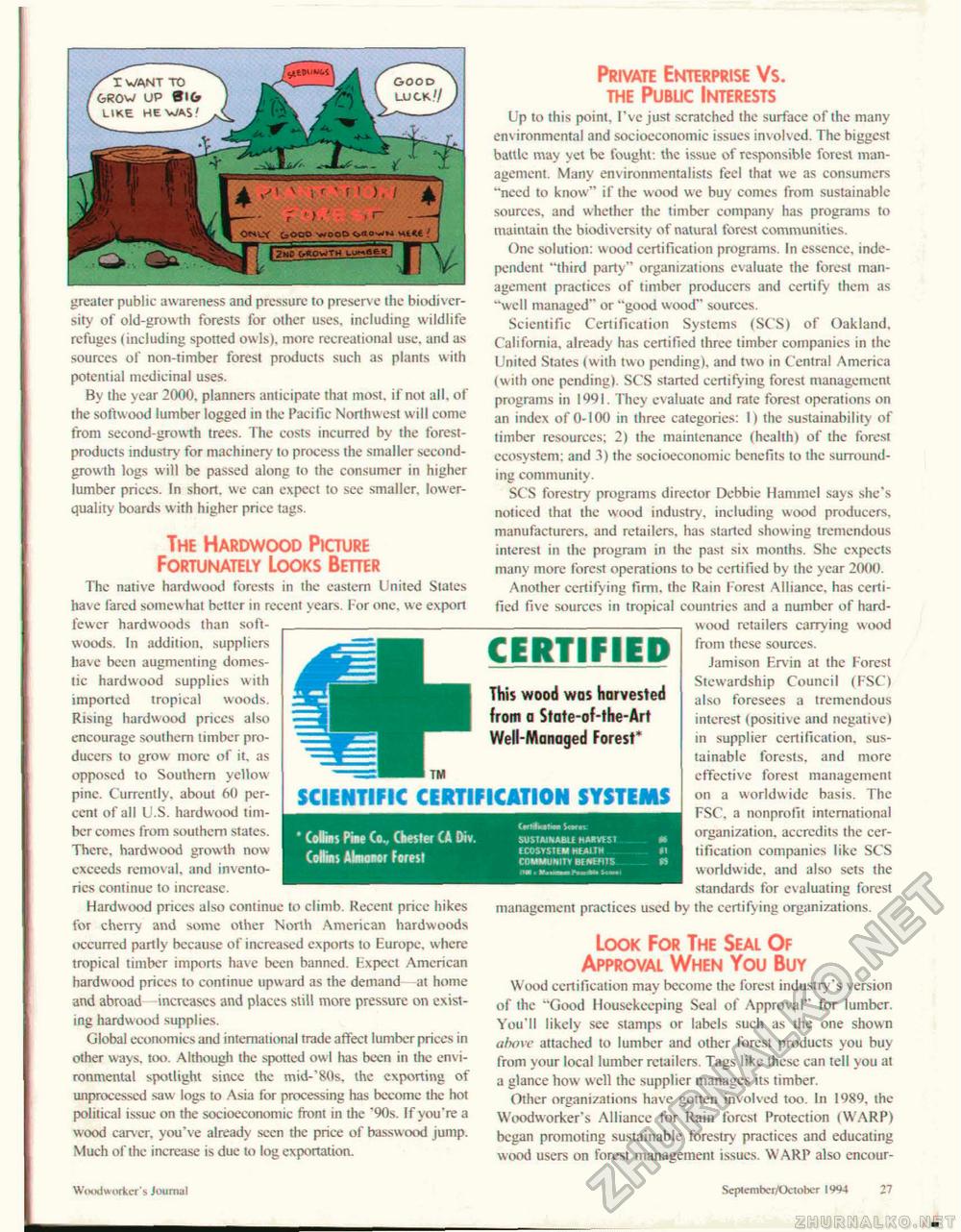

greater public awareness and pressure to preserve the biodiversity of old-growth forests for other uses, including wildlife refuges (including spotted owls), more recreational use, and as sources of non-timber forest products such as plants w ith potential medicinal uses. By the year 2000. planners anticipate that most, if not all, of the softwood lumber logged in the Pacific Northwest will come from second-growth trees. The costs incurred by the forest-products industry for machinery to process the smaller second-growth logs will be passed along to the consumer in higher lumber prices. In short, we can expect to see smaller, lower-quality boards w ith higher price tags. The Hardwood Picture Fortunately Looks Better The native hardwood forests in the eastern United States ha\ e fared somew hat better in recent years. For one. we export fewer hardwoods than softwoods. In addition, suppliers have been augmenting domestic hardwood supplies with imported tropical woods. Rising hardwood prices also encourage southern limber producers to grow more of it, as opposed to Southern yellow pine. Currently, about 60 percent of all U.S. hardwood timber comes from southern states. There, hardwood growth now exceeds removal, and inventories continue to increase. Hardwood prices also continue to climb. Recent price hikes for cherry and some other North American hardwoods occurred partly because of increased exports to Europe, where tropical timber imports have been banned. Expect American hardwood prices to continue upward as the demand at home and abroad increases and places still more pressure on existing hardwood supplies. Global economics and international trade affect lumber prices in other ways. too. Although the spotted owl has been in the environmental spotlight since the mid-'80s, the exporting of unprocessed saw logs to Asia for processing has become the hot political issue on the socioeconomic front in the "90s. If you're a wood carver, you've already seen the price of bass wood jump. Much of the increase is due to log exportation. Private Enterprise Vs. the Public Interests Up to this point. I've just scratched the surface of the many environmental and socioeconomic issues involved. The biggest battle may yet be fought: the issue of responsible forest management. Many environmentalists feel that we as consumers "need to know" if the wood we buy comes from sustainable sources, and whether the timber company has programs to maintain the biodiversity of natural forest communities. One solution: wood certification programs. In essence, independent "third party" organizations evaluate the forest management practices of timber producers and certify them as "well managed" or "good wood" sources. Scientific Certification Systems (SCS) of Oakland. California, already has certified three timber companies in the United States (with two pending), and two in Central America (with one pending). SCS started certifying forest management programs in 1991. They evaluate and rate forest operations on an index of 0-100 in three categories: I) the sustainability of timber resources; 2) the maintenance (health) of the forest ecosystem: and 3) the socioeconomic benefits to the surrounding community. SCS forestry programs director Debbie Hammel says she's noticed that the wood industry, including wood producers, manufacturers, and retailers, has started showing tremendous interest in the program in the past six months. She expects many more forest operations to be certified by the year 20(H). Another certifying firm, the Rain Forest Alliance, has certified five sources in tropical countries and a number of hardwood retailers carrying wood from these sources. Jamison Ervin at the Forest Stewardship Council (l-'SC) also foresees a tremendous interest (positive and negative) in supplier certification, sustainable forests, and more effective forest management on a worldwide basis. The FSC. a nonprofit international organization, accredits the certification companies like SCS worldwide, and also sets the standards for evaluating forest management practices used by the certifying organizations. Look For The Seal Of Approval When You Buy Wood certification may become the forest industry's version of the "Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval" for lumber. You'll likely see stamps or labels such as the one shown above attached to lumber and other forest products you buy from your local lumber retailers. Tags like these can tell you at a glance how well the supplier manages its timber. Other organizations have gotten involved too. in 1989, the Woodworker's Alliance for Rain forest Protection (WARP) began promoting sustainable forestry practices and educating wood users on forest management issues. WARP also encour CERTIFIED This wood wos harvested from o Slate-of-the-Art Well-Manoged Forest* SCIENTIFIC CERTIFICATION SYSTEMS (olfa; Pine Co., Chester CA Div, Collins Alnomr forest (Ntihtlho. S<»<r SUSTAINABLE HAKVESI E COSTStEM KEJU-tH COMMUNITY BENEFITS Woodworker" < Journal September/October 1904 27 |