Woodworker's Journal 1994-18-6, страница 23

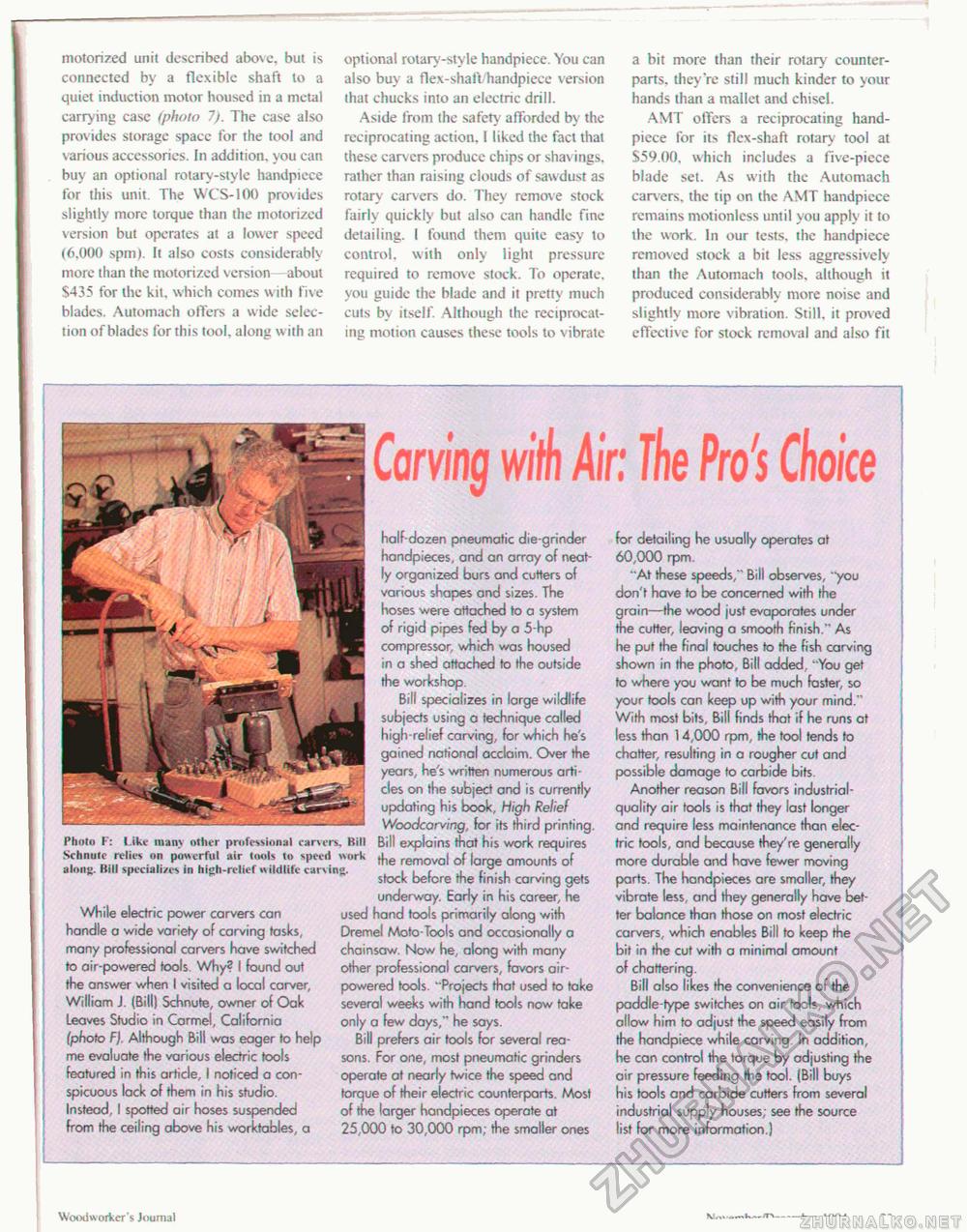

motorized unit described above, but is connected by a flexible shaft to a quiet induction motor housed in a metal carrying case (photo 7). The case also provides storage space for the tool and various accessories. In addition, you can buy an optional rotarv-stylc handpiece for this unit. The WCS-100 provides slightly more torque than the motorized version but operates at a lower speed (6.000 spm). It also costs considerably more than the motorized version—about S435 for the kit. which comes with five blades. Automach offers a wide selection of blades for this tool, along w ith an optional rotary-style handpiece. You can also buy a flex-shaft handpiecc version that chucks into an electric drill. Aside from the safety afforded by the reciprocating action, I liked the fact that these carvers produce chips or shavings, rather than raising clouds of sawdust as rotary carvers do. They remove stock fairly quickly but also can handle fine detailing, I found them quite easy to control, with only light pressure required to remove stock. To operate, you guide the blade and it pretty much cuts bv itself. Although the reciprocating motion causes these tools to vibrate a bit more than their rotary counterparts. they're still much kinder to your hands than a mallet and chisel. AMT offers a reciprocating handpiece for its flex-shaft rotary tool at S59.00. which includes a five-piece blade set. As with the Automach carvers, the tip on the AMT handpiece remains motionless until you apply it to the work. In our tests, the handpiece removed stock a bit less aggressively than the Automach tools, although it produced considerably more noise and slightly more vibration. Still, it proved effective for stock removal and also fit Carving with Air: The Pro's Choice Photo F: Like many other professional carvers. Hill Schnute relies on powerful air tools to speed work along. Bill specializes in high-relief wildlife carving. While electric power corvers can handle o wide variety of carving tasks, many professional carvers have switched to air-powered tools. Why? I found out the answer when I visited a local carver, William J. (Bill) Schnute, owner of Oak Leaves Studio in Carmel, California (photo F). Although Bill was eager to help me evaluate the various electric tools featured in this article, I noticed a conspicuous lack of them in his studio. Instead, I spotted air hoses suspended from the ceiling above his worktables, a half-dozen pneumatic die-grinder handpieces, and an array of neatly organized burs and cutters of various shapes and sizes. The hoses were attached to a system of rigid pipes fed by a 5-hp compressor, which was housed in a shed attached to the outside the workshop. Bill specializes in large wildlife subjects using a technique called high-relief carving, for which he's gained national acclaim. Over the years, he's written numerous articles on the subject and is currently updating his book, High Relief Woodcarving, for its third printing. Bill explains that his work requires the removal of large amounts of stock before the finish carving gets underway. Early in his career, he used hand tools primarily along with Dremel Moto-Tools and occasionally a chainsaw. Now he, along with many other professional carvers, favors air-powered tools. "Projects that used to take several weeks with hand tools now take only a few days," he soys. Bill prefers air fools for several reasons. For one, most pneumatic grinders operate at nearly twice the speed and torque of their electric counterparts. Most of the larger handpieces operate at 25,000 to 30,000 rpm; the smaller ones for detailing he usually operates at 60,000 rpm. "At these speeds," Bill observes, "you don't have to be concerned with the grain—the wood just evaporates under the cutter, leaving a smooth finish," As he put the final touches to the fish carving shown in the photo, Bill added, "You get to where you want to be much faster, so your tools can keep up with your mind." With most bits, Bill finds that if he runs at less than 14,000 rpm, the tool tends to chatter, resulting in a rougher cut and possible damage to carbide bits. Another reason Bill favors industrial-quality air tools is that they last longer and require less maintenance than electric tools, and because they're generally more durable and have fewer moving parts. The handpieces are smaller, they vibrate less, and they generally have better balance than those on most electric carvers, which enables Bill to keep the bit in the cut with a minimal amount of chattering. Bill also likes the convenience of the paddle-type switches on air tools, which allow him to adjust the speed easily from the handpiece while carving. In addition, he can control the torque by adjusting the air pressure feeding the tool. (Bill buys his tools and carbide cutters from several industrial supply houses; see the source list for more information.) Woodworker s Journal M,,. .....U-.- /T-I—-- |