Creative Woodworks & crafts 2005-01, страница 52

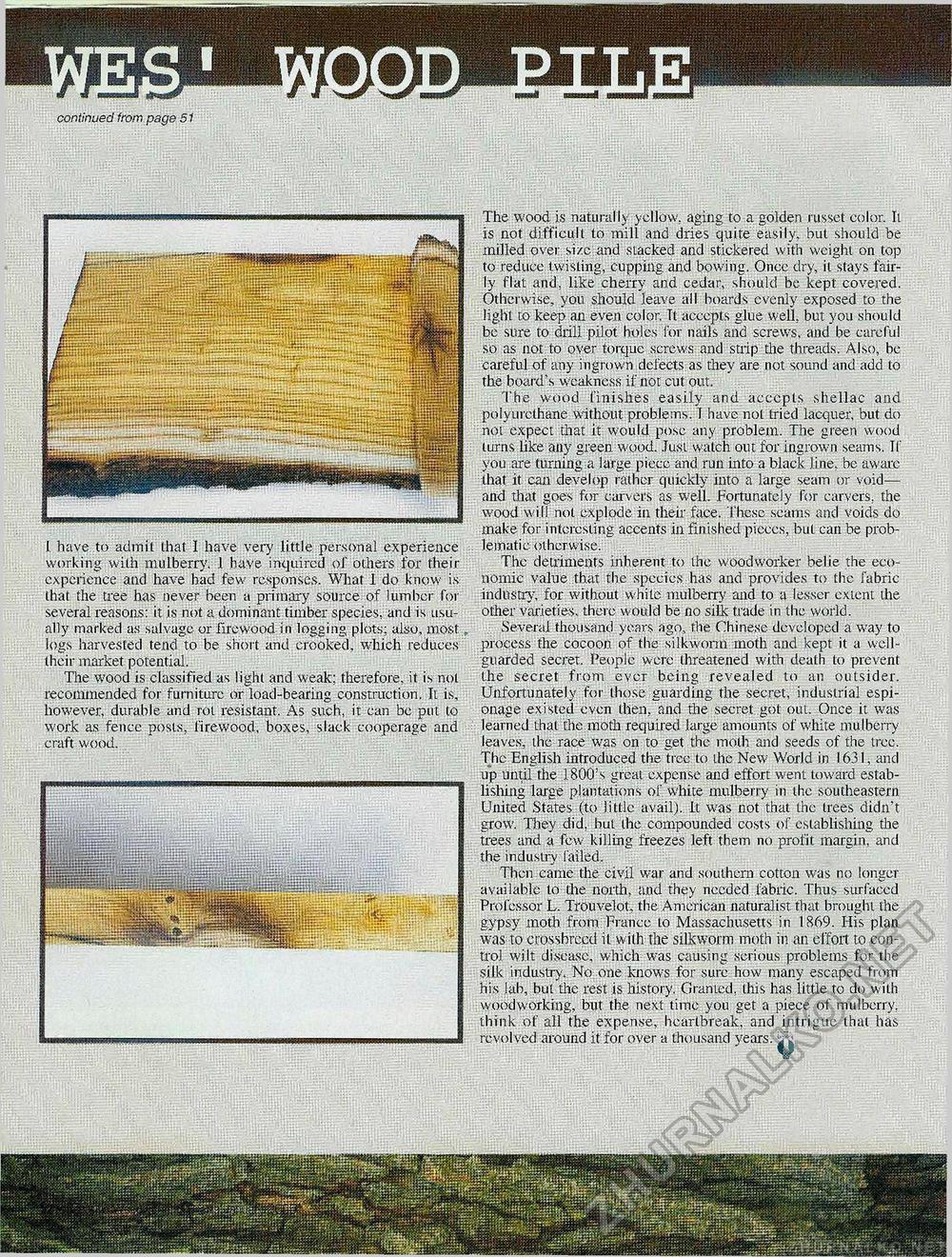

continued from page 51 The wood is naturally yellow, aging to a golden russet color. It is not difficult to mill and dries quite easily, but should be milled over size and slacked and stickered with weight on top to reduce twisting, cupping and bowing. Once dry, it stays fairly flat and, like cherry and cedar, should be kept covered. Otherwise, you should leave all boards evenly exposed to the light to keep an even color. It accepts glue well, but you should be sure to drill pilot holes for nails and screws, and be careful so as not to over torque screws and strip the threads. Also, be careful of any ingrown defects as they are not sound and add to the board's weakness if not cut out. The wood finishes easily and accepts shellac and polyurethane without problems. I have not tried lacquer, but do not expect that it would pose any problem. The green wood turns like any green wood. Just watch out for ingrown seams. If you are turning a large piece and run into a black line, be aware that it can develop rather quickly into a large seam or void— and that goes for carvers as well. Fortunately for carvers, the wood wilT not explode in their face. These scams and voids do make for interesting accents in finished pieces, but can be problematic otherwise. The detriments inherent to the woodworker belie the economic value that the species has and provides to the fabric industry, for without white mulberry and to a lesser extent the other varieties, there would be 110 silk trade in the world. Several thousand years ago, fhe Chinese developed a way to process the cocoon of the silkworm moth and kept it a wcll-guarded secret. People were threatened with death to prevent the secret from ever being revealed to an outsider. Unfortunately for those guarding the secret, industrial espionage existed even then, and the secret got out. Once it was learned that the moth required large amounts of white mulberry leaves, the race was on to get the moth and seeds of the tree. The English introduced the tree to the New: World in 1631, and up until the 1800:s great expense and effort went toward establishing large plantations of white mulberry in the southeastern United States (to little avail). It was not that the trees didn't grow. They did. but the compounded costs of establishing the trees and a few killing freezes left them no profit margin, and the industry failed. Then came the civil war and southern cotton was no longer available to the north, and they needed fabric. Thus surfaced Professor L. Trouvelot, the American naturalist, that brought ihe gypsy moth from France to Massachusetts in 1869. His plan was to crossbreed it with the silkworm moth in an effort to control wilt disease, which was causing serious problems for the silk industry. No one knows for sure how many escaped from his lab, but the rest is history. Granted, this has little to do with woodworking, but the next time you get a piece of mulberry, think of all the expense, heartbreak, and intrigue that has revolved around it for over a thousand years, ij't I have to admit that I have very little personal experience working with mulberry. 1 have inquired of others for their experience and have bad few responses. What 1 do know is that the tree has never been a primary source of lumber for several reasons: it is not a dominant timber species, and is usually marked as salvage or firewood in logging plots; also, most logs harvested tend to be short and crooked, which reduces their market potential. The wood is classified as light and weak; therefore, it is not recommended for furniture or load-bearing construction. It is, however, durable and rot resistant. As such, it can be put to work as fence posts, firewood, boxes, slack cooperage and craft wood. |