Popular Woodworking 2005-12 № 152, страница 78

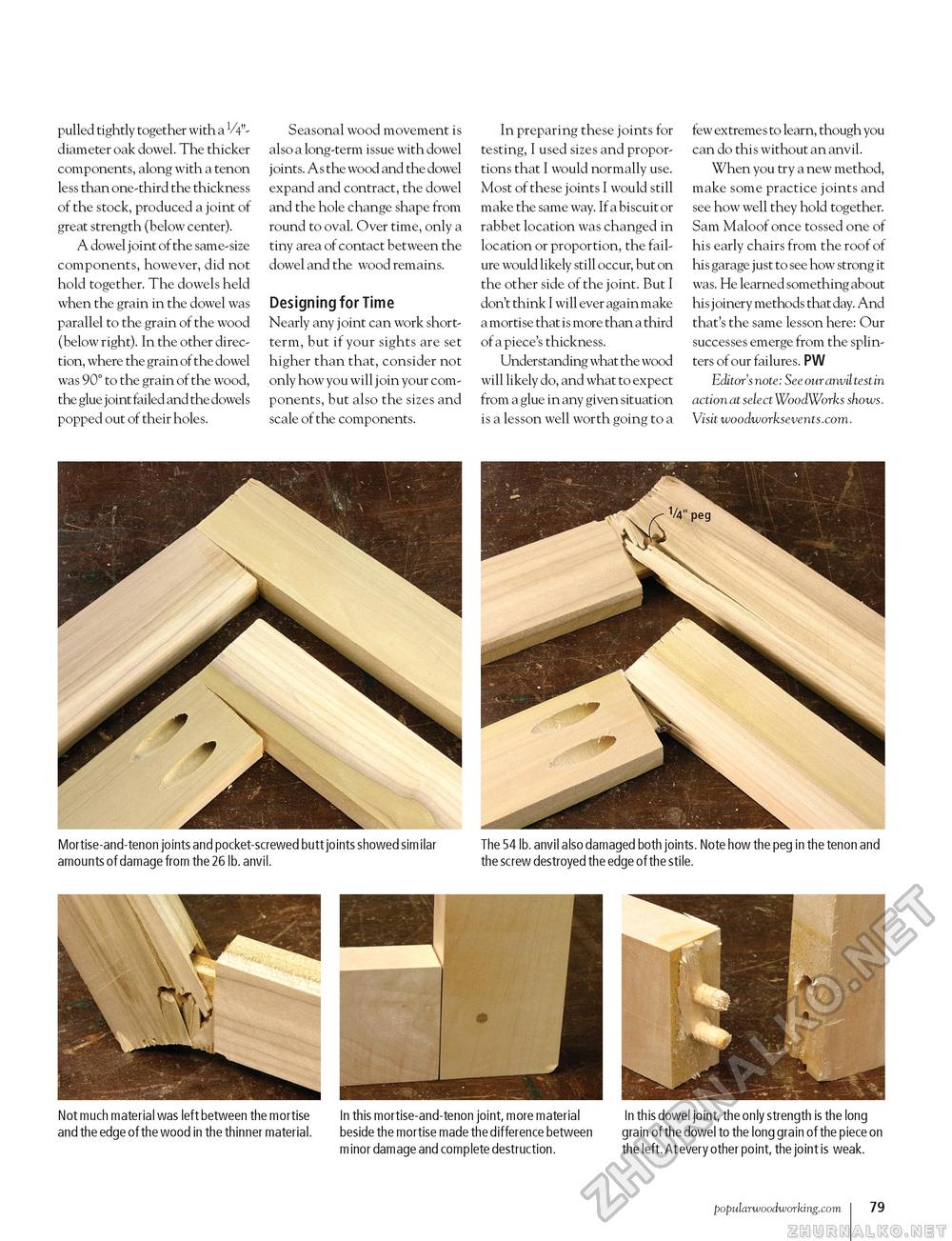

pulled tightly together with a V4"-diameter oak dowel. The thicker components, along with a tenon less than one-third the thickness of the stock, produced a joint of great strength (below center). A dowel joint of the same-size components, however, did not hold together. The dowels held when the grain in the dowel was parallel to the grain of the wood (below right). In the other direction, where the grain of the dowel was 90° to the grain of the wood, the glue joint failed and the dowels popped out of their holes. Seasonal wood movement is also a long-term issue with dowel joints. As the wood and the dowel expand and contract, the dowel and the hole change shape from round to oval. Over time, only a tiny area of contact between the dowel and the wood remains. Designing for Time Nearly any joint can work short-term, but if your sights are set higher than that, consider not only how you will j oin your components, but also the sizes and scale of the components. In preparing these joints for testing, I used sizes and proportions that I would normally use. Most of these joints I would still make the same way. If a biscuit or rabbet location was changed in location or proportion, the failure would likely still occur, but on the other side of the joint. But I don't think I will ever again make a mortise that is more than a third of a piece's thickness. Understanding what the wood will likely do, and what to expect from a glue in any given situation is a lesson well worth going to a few extreme s to learn, though you can do this without an anvil. When you try a new method, make some practice joints and see how well they hold together. Sam Maloof once tossed one of his early chairs from the roof of his garage just to see how strong it was. He learned something about his j oinery methods that day. And that's the same lesson here: Our successes emerge from the splinters of our failures. PW Editor's note: See our anvil test in action at select WoodWorks shows. Visit woodworksevents.com. Mortise-and-tenon joints and pocket-screwed butt joints showed similar amounts of damage from the 26 lb. anvil. The 54 lb. anvil also damaged both joints. Note how the peg in the tenon and the screw destroyed the edge of the stile. Not much material was left between the mortise and the edge of the wood in the thinner material. In this mortise-and-tenon joint, more material beside the mortise made the difference between minor damage and complete destruction. In this dowel joint, the only strength is the long grain of the dowel to the long grain of the piece on the left. At every other point, the joint is weak. popularwoodworking.com 33 |