Popular Woodworking 2007-04 № 161, страница 21

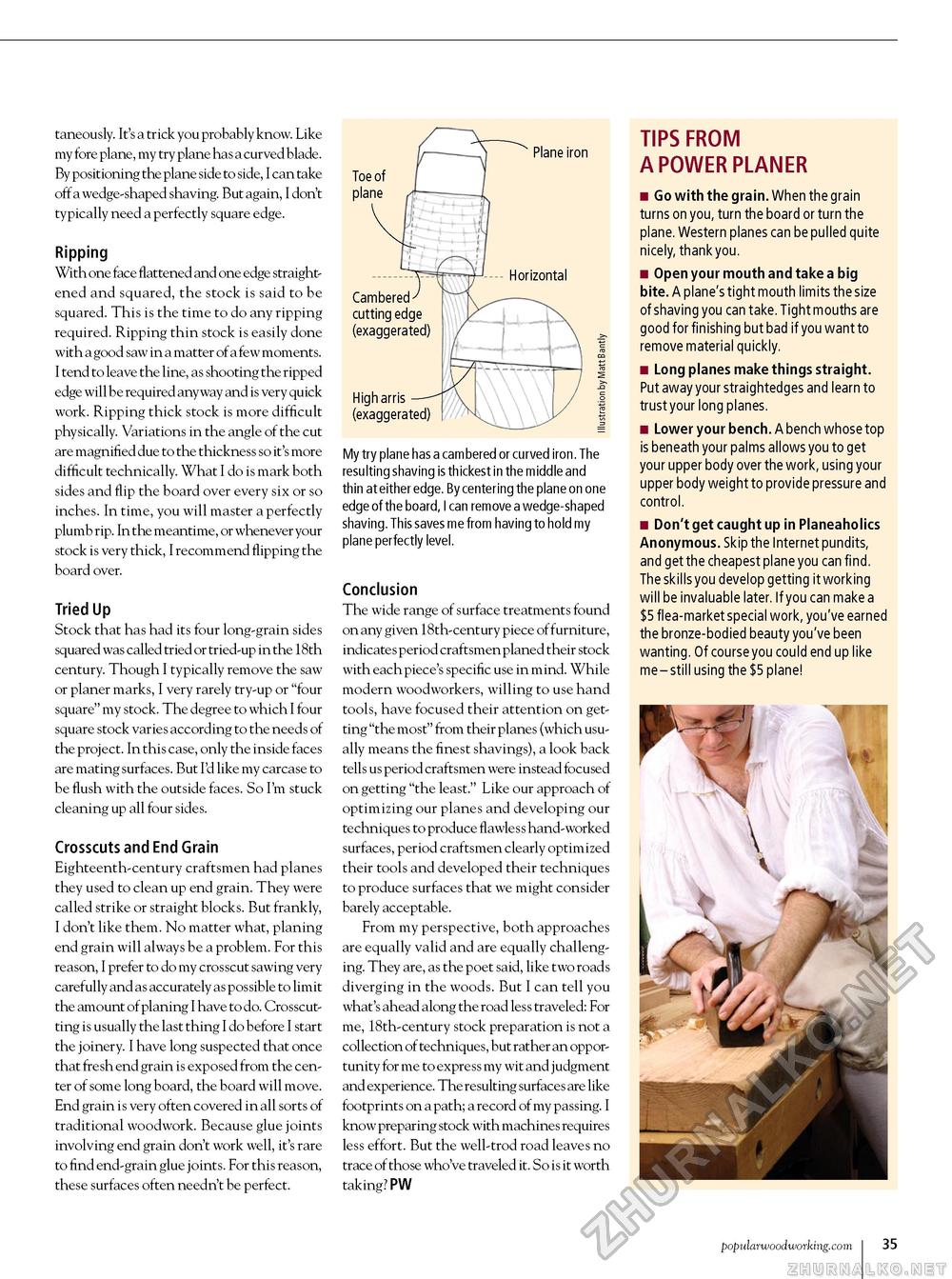

taneously. It's a trick you probably know. Like my fore plane, my try plane has a curved blade. By positioning the plane side to side, I can take off a wedge-shaped shaving. But again, I don't typically need a perfectly square edge. Ripping With one face flattened and one edge straightened and squared, the stock is said to be squared. This is the time to do any ripping required. Ripping thin stock is easily done with a good saw in a matter of a few moments. I tend to leave the line, as shooting the ripped edge will be required anyway and is very quick work. Ripping thick stock is more difficult physically. Variations in the angle of the cut are magnified due to the thickness so it's more difficult technically. What I do is mark both sides and flip the board over every six or so inches. In time, you will master a perfectly plumb rip. In the meantime, or whenever your stock is very thick, I recommend flipping the board over. Tried Up Stock that has had its four long-grain sides squared was called tried or tried-up in the 18th century. Though I typically remove the saw or planer marks, I very rarely try-up or "four square" my stock. The degree to which I four square stock varies according to the needs of the project. In this case, only the inside faces are mating surfaces. But I'd like my carcase to be flush with the outside faces. So I'm stuck cleaning up all four sides. Crosscuts and End Grain Eighteenth-century craftsmen had planes they used to clean up end grain. They were called strike or straight blocks. But frankly, I don't like them. No matter what, planing end grain will always be a problem. For this reason, I prefer to do my crosscut sawing very carefully and as accurately as possible to limit the amount of planing I have to do. Crosscut-ting is usually the last thing I do before I start the joinery. I have long suspected that once that fresh end grain is exposed from the center of some long board, the board will move. End grain is very often covered in all sorts of traditional woodwork. Because glue joints involving end grain don't work well, it's rare to find end-grain glue joints. For this reason, these surfaces often needn't be perfect. My try plane has a cambered or curved iron. The resulting shaving is thickest in the middle and thin at either edge. By centering the plane on one edge of the board, I can remove a wedge-shaped shaving. This saves me from having to hold my plane perfectly level. Conclusion The wide range of surface treatments found on any given 18th-century piece of furniture, indicates period craftsmen planed their stock with each piece's specific use in mind. While modern woodworkers, willing to use hand tools, have focused their attention on getting "the most" from their planes (which usually means the finest shavings), a look back tells us period craftsmen were instead focused on getting "the least." Like our approach of optimizing our planes and developing our techniques to produce flawless hand-worked surfaces, period craftsmen clearly optimized their tools and developed their techniques to produce surfaces that we might consider barely acceptable. From my perspective, both approaches are equally valid and are equally challenging. They are, as the poet said, like two roads diverging in the woods. But I can tell you what's ahead along the road less traveled: For me, 18th-century stock preparation is not a collection of techniques, but rather an opportunity for me to express my wit and judgment and experience. The resulting surfaces are like footprints on a path; a record of my passing. I know preparing stock with machines requires less effort. But the well-trod road leaves no trace of those who've traveled it. So is it worth taking? PW TIPS FROM A POWER PLANER ■ Go with the grain. When the grain turns on you, turn the board or turn the plane. Western planes can be pulled quite nicely, thank you. ■ open your mouth and take a big bite. A plane's tight mouth limits the size of shaving you can take. Tight mouths are good for finishing but bad if you want to remove material quickly. ■ long planes make things straight. Put away your straightedges and learn to trust your long planes. ■ lower your bench. A bench whose top is beneath your palms allows you to get your upper body over the work, using your upper body weight to provide pressure and control. ■ Don't get caught up in planeaholics anonymous. Skip the Internet pundits, and get the cheapest plane you can find. The skills you develop getting it working will be invaluable later. If you can make a $5 flea-market special work, you've earned the bronze-bodied beauty you've been wanting. Of course you could end up like me - still using the $5 plane! popularwoodworking.com I 35 |