Popular Woodworking 2009-11 № 179, страница 8

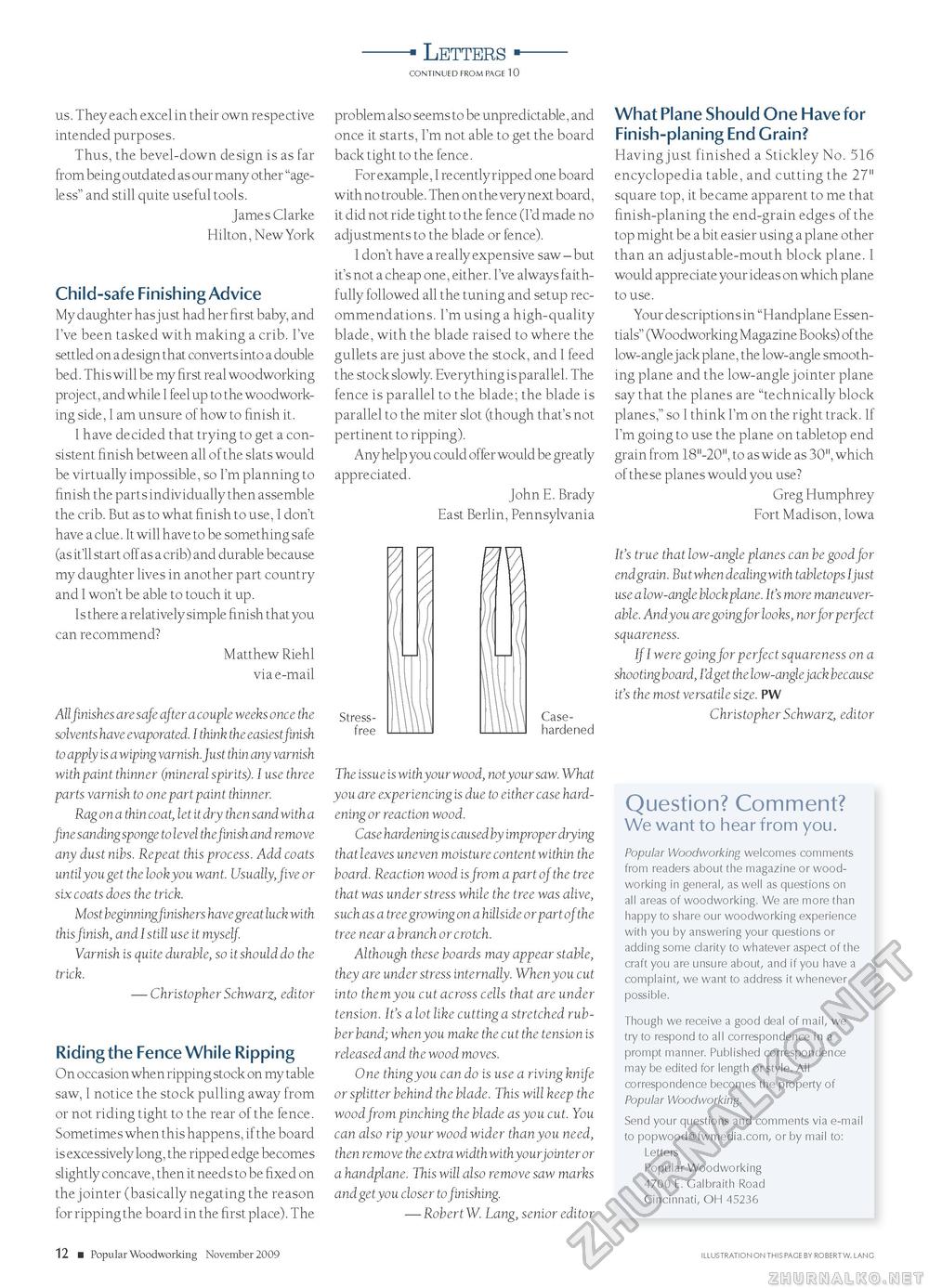

us. They each excel in their own respective intended purposes. Thus, the bevel-down design is as far from being outdated as our many other "ageless" and still quite useful tools. James Clarke Hilton, New York Child-safe Finishing Advice My daughter has just had her first baby, and I've been tasked with making a crib. I've settled on a design that converts into a double bed. This will be my first real woodworking project, and while I feel up to the woodworking side, I am unsure of how to finish it. I have decided that trying to get a consistent finish between all of the slats would be virtually impossible, so I'm planning to finish the parts individually then assemble the crib. But as to what finish to use, I don't have a clue. It will have to be something safe (as it'll start off as a crib) and durable because my daughter lives in another part country and I won't be able to touch it up. Is there a relatively simple finish that you can recommend? Matthew Riehl via e-mail All finishes are safe after a couple weeks once the solvents have evaporated. I think the easiest finish to apply is a wiping varnish. Just thin any varnish with paint thinner (mineral spirits). I use three parts varnish to one part paint thinner. Rag on a thin coat, let it dry then sand with a fine sanding sponge to level the finish and remove any dust nibs. Repeat this process. Add coats until you get the look you want. Usually, five or six coats does the trick. Most beginningfinishers have great luck with this finish, and I still use it myself. Varnish is quite durable, so it should do the trick. — Christopher Schwarz, editor Riding the Fence While Ripping On occasion when ripping stock on my table saw, I notice the stock pulling away from or not riding tight to the rear of the fence. Sometimes when this happens, if the board is excessively long, the ripped edge becomes slightly concave, then it needs to be fixed on the jointer (basically negating the reason for ripping the board in the first place). The Letters CONTiNUED FROM PAGE 1 0 problem also seems to be unpredictable, and once it starts, I'm not able to get the board back tight to the fence. For example, I recently ripped one board with no trouble. Then on the very next board, it did not ride tight to the fence (I'd made no adjustments to the blade or fence). I don't have a really expensive saw - but it's not a cheap one, either. I've always faithfully followed all the tuning and setup recommendations. I'm using a high-quality blade, with the blade raised to where the gullets are just above the stock, and I feed the stock slowly. Everything is parallel. The fence is parallel to the blade; the blade is parallel to the miter slot (though that's not pertinent to ripping). Any help you could offer would be gre atly appreciated. John E. Brady East Berlin, Pennsylvania What Plane Should One Have for Finish-planing End Grain? Having just finished a Stickley No. 516 encyclopedia table, and cutting the 27" square top, it became apparent to me that finish-planing the end-grain edges of the top might be a bit easier using a plane other than an adjustable-mouth block plane. I would appreciate your ideas on which plane to use. Your descriptions in "Handplane Essentials" (Woodworking Magazine Books) of the low-angle jack plane, the low-angle smoothing plane and the low-angle jointer plane say that the planes are "technically block planes," so I think I'm on the right track. If I'm going to use the plane on tabletop end grain from 18"-20", to as wide as 30"", which of these planes would you use? Greg Humphrey Fort Madison, Iowa Stress-free Case-hardened It's true that low-angle planes can be good for end grain. But when dealing with tabletops I just use a low-angle block plane. It's more maneuver-able. Andyou are goingfor looks, nor for perfect squareness. If I were goingfor perfect squareness on a shooting board, I'd get the low-angle jack because it's the most versatile size. PW Christopher Schwarz, editor The issue is with your wood, not your saw. What you are experiencing is due to either case hardening or reaction wood. Case hardening is caused by improper drying that leaves uneven moisture content within the board. Reaction wood is from a part of the tree that was under stress while the tree was alive, such as a tree growing on a hillside or part of the tree near a branch or crotch. Although these boards may appear stable, they are under stress internally. When you cut into them you cut across cells that are under tension. It's a lot like cutting a stretched rubber band; when you make the cut the tension is released and the wood moves. One thing you can do is use a riving knife or splitter behind the blade. This will keep the wood from pinching the blade as you cut. You can also rip your wood wider than you need, then remove the extra width withyour jointer or a handplane. This will also remove saw marks and get you closer to finishing. — Robert W. Lang, senior editor Question? Comment? We want to hear from you. Popular Woodworking welcomes comments from readers about the magazine or woodworking in general, as well as questions on all areas of woodworking. We are more than happy to share our woodworking experience with you by answering your questions or adding some clarity to whatever aspect of the craft you are unsure about, and if you have a complaint, we want to address it whenever possible. though we receive a good deal of mail, we try to respond to all correspondence in a prompt manner. published correspondence may be edited for length or style. Ah correspondence becomes the property of Popular Woodworking. Send your questions and comments via e-mail to popwood@fwmedia.com, or by mail to: letters popular Woodworking 4700 E. galbraith road cincinnati, oh 45236 12 ■ Popular Woodworking November 2009 illustration on this pace by robert w. lanc |