Woodworker's Journal 1984-8-6, страница 19

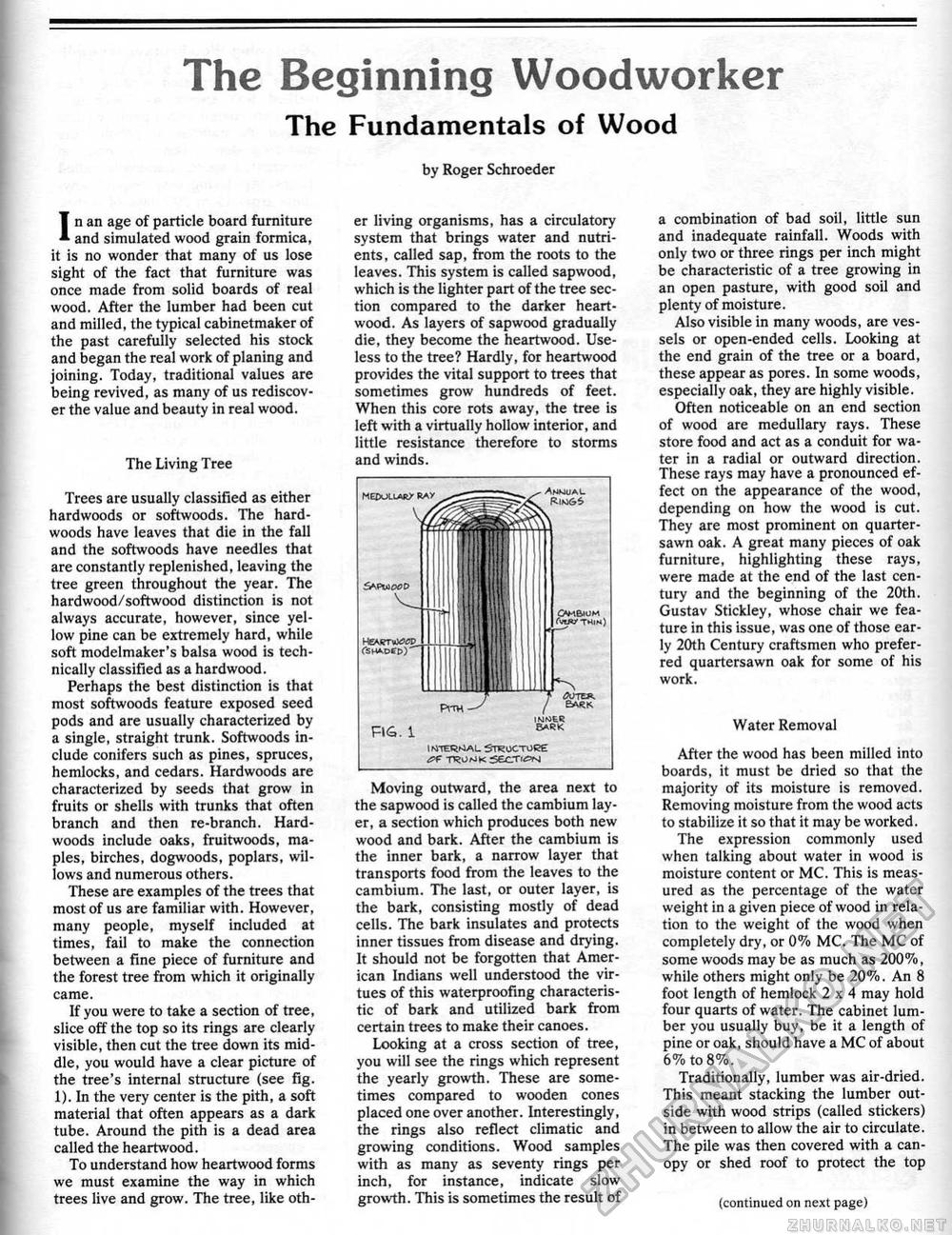

The Beginning Woodworker The Fundamentals of Wood by Roger Schroeder In an age of particle board furniture and simulated wood grain formica, it is no wonder that many of us lose sight of the fact that furniture was once made from solid boards of real wood. After the lumber had been cut and milled, the typical cabinetmaker of the past carefully selected his stock and began the real work of planing and joining. Today, traditional values are being revived, as many of us rediscover the value and beauty in real wood. The Living Tree Trees are usually classified as either hardwoods or softwoods. The hardwoods have leaves that die in the fall and the softwoods have needles that are constantly replenished, leaving the tree green throughout the year. The hardwood/softwood distinction is not always accurate, however, since yellow pine can be extremely hard, while soft modelmaker's balsa wood is technically classified as a hardwood. Perhaps the best distinction is that most softwoods feature exposed seed pods and are usually characterized by a single, straight trunk. Softwoods include conifers such as pines, spruces, hemlocks, and cedars, Hardwoods are characterized by seeds that grow in fruits or shells with trunks that often branch and then re-branch. Hardwoods include oaks, fruitwoods, maples, birches, dogwoods, poplars, willows and numerous others. These are examples of the trees that most of us are familiar with. However, many people, myself included at times, fail to make the connection between a fine piece of furniture and the forest tree from which it originally came. If you were to take a section of tree, slice off the top so its rings are clearly visible, then cut the tree down its middle, you would have a clear picture of the tree's internal structure (see fig. 1). In the very center is the pith, a soft material that often appears as a dark tube. Around the pith is a dead area called the heartwood. To understand how heartwood forms we must examine the way in which trees live and grow. The tree, like oth er living organisms, has a circulatory system that brings water and nutrients, called sap, from the roots to the leaves. This system is called sapwood, which is the lighter part of the tree section compared to the darker heart-wood. As layers of sapwood gradually die, they become the heartwood. Useless to the tree? Hardly, for heartwood provides the vital support to trees that sometimes grow hundreds of feet. When this core rots away, the tree is left with a virtually hollow interior, and little resistance therefore to storms and winds. Moving outward, the area next to the sapwood is called the cambium layer, a section which produces both new wood and bark. After the cambium is the inner bark, a narrow layer that transports food from the leaves to the cambium. The last, or outer layer, is the bark, consisting mostly of dead cells. The bark insulates and protects inner tissues from disease and drying. It should not be forgotten that American Indians well understood the virtues of this waterproofing characteristic of bark and utilized bark from certain trees to make their canoes. Looking at a cross section of tree, you will see the rings which represent the yearly growth. These are sometimes compared to wooden cones placed one over another. Interestingly, the rings also reflect climatic and growing conditions. Wood samples with as many as seventy rings per inch, for instance, indicate slow growth. This is sometimes the result of a combination of bad soil, little sun and inadequate rainfall. Woods with only two or three rings per inch might be characteristic of a tree growing in an open pasture, with good soil and plenty of moisture. Also visible in many woods, are vessels or open-ended cells. Looking at the end grain of the tree or a board, these appear as pores. In some woods, especially oak, they are highly visible. Often noticeable on an end section of wood are medullary rays. These store food and act as a conduit for water in a radial or outward direction. These rays may have a pronounced effect on the appearance of the wood, depending on how the wood is cut. They are most prominent on quarter-sawn oak. A great many pieces of oak furniture, highlighting these rays, were made at the end of the last century and the beginning of the 20th. Gustav Stickley, whose chair we feature in this issue, was one of those early 20th Century craftsmen who preferred quartersawn oak for some of his work. Water Removal After the wood has been milled into boards, it must be dried so that the majority of its moisture is removed. Removing moisture from the wood acts to stabilize it so that it may be worked. The expression commonly used when talking about water in wood is moisture content or MC. This is measured as the percentage of the water weight in a given piece of wood in relation to the weight of the wood when completely dry, or 0% MC. The MC of some woods may be as much as 200%, while others might only be 20%. An 8 foot length of hemlock 2x4 may hold four quarts of water. The cabinet lumber you usually buy, be it a length of pine or oak, should have a MC of about 6% to 8%. Traditionally, lumber was air-dried. This meant stacking the lumber outside with wood strips (called stickers) in between to allow the air to circulate. The pile was then covered with a canopy or shed roof to protect the top (continued on next page) RG. 1 MEpULLAR/ RAY ^WMUAL INTERhiAL STCUC-TOeg tromk :5£c"ri<=f-4 |