Woodworker's Journal 1993-17-4, страница 24

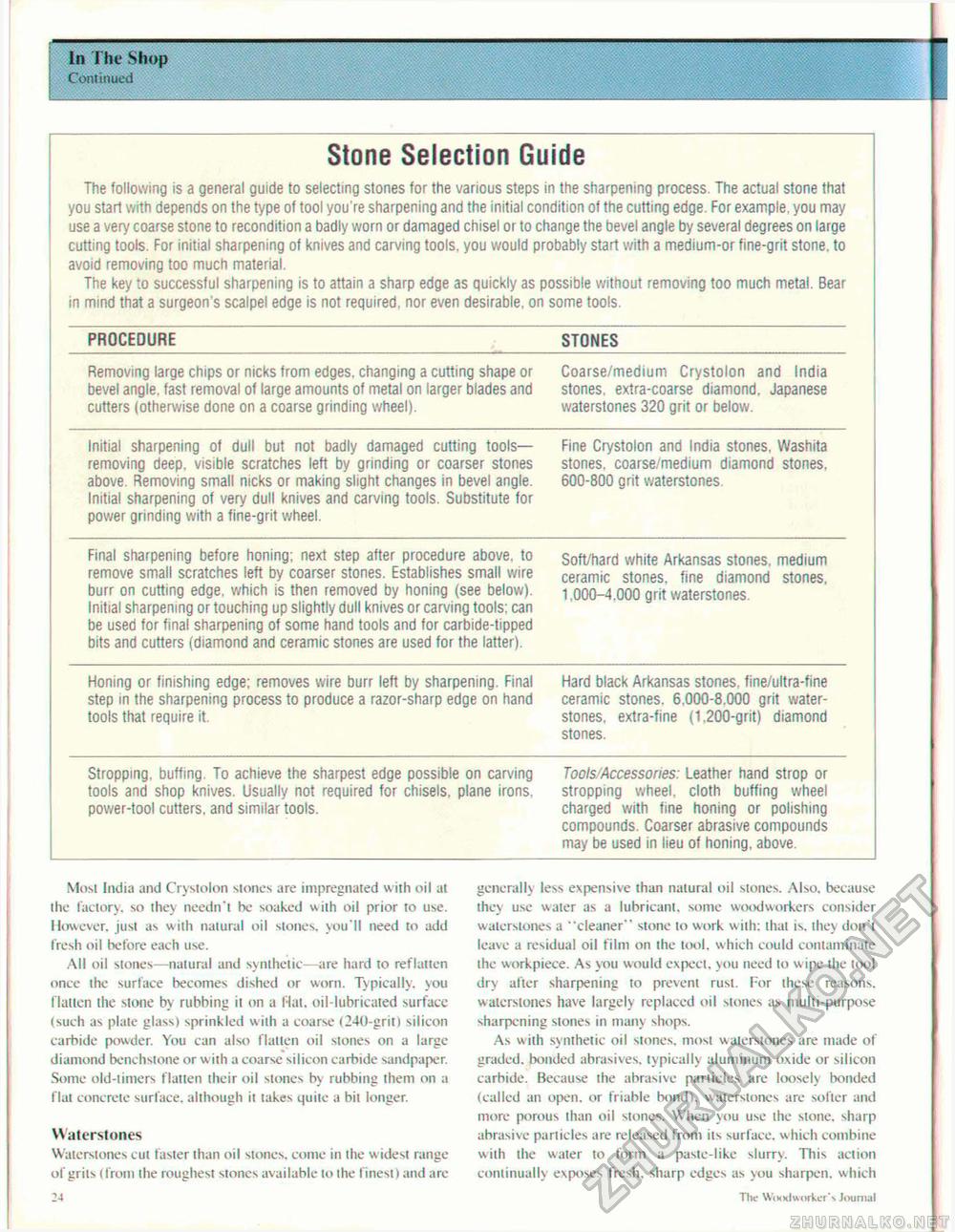

Stone Selection Guide The following is a general guide to selecting stones for the various steps in the sharpening process. The actual stone that you start with depends on the type of tool you're sharpening and the initial condition of the cutting edge. For example, you may use a very coarse stone to recondition a badly worn or damaged chisel or to change the bevel angle by several degrees on large cutting tools. For initial sharpening of knives and carving tools, you would probably start with a medium-or fine-grit stone, to avoid removing too much material. The key to successful sharpening is to attain a sharp edge as quickly as possible without removing too much metal. Bear in mind that a surgeon's scalpel edge is not required, nor even desirable, on some tools. PROCEDURE STONES Removing large chips or nicks from edges, changing a cutting shape or Coarse/medium Crystolon and India bevel angle, fast removal of large amounts of metal on larger blades and stones, extra-coarse diamond, Japanese cutters (otherwise done on a coarse grinding wheel). waterstones 320 grit or below. Initial sharpening of dull but not badly damaged cutting tools— Fine Crystolon and India stones. Washita removing deep, visible scratches left by grinding or coarser stones stones, coarse/medium diamond stones, above. Removing small nicks or making slight changes in bevel angle. 600-800 grit waterstones. Initial sharpening of very dull knives and carving tools. Substitute for power grinding with a fine-grit wheel. Final sharpening before honing; next step after procedure above, to Soft/hard white Arkansas stones, medium remove small scratches left by coarser stones. Establishes small wire ceramic stones, fine diamond stones, burr on cutting edge, which is then removed by honing (see below). 1,000-4.000 grit waterstones. Initial sharpening or touching up slightly dull knives or carving tools: can be used for final sharpening of some hand tools and for carbide-tipped bits and cutters (diamond and ceramic stones are used for the latter). Honing or finishing edge; removes wire burr left by sharpening. Final Hard black Arkansas stones, fine/ultra-fine step in the sharpening process to produce a razor-sharp edge on hand ceramic stones. 6.000-8.000 grit water-tools that require it. stones, extra-fine (1.200-grit) diamond stones. Stropping, buffing. To achieve the sharpest edge possible on carving Tools/Accessories: Leather hand strop or tools and shop knives. Usually not required for chisels, plane irons, stropping wheel, cloth buffing wheel power-tool cutters, and similar tools. charged with fine honing or polishing compounds. Coarser abrasive compounds may be used in lieu of honing, above. Most India and Crystolon stones are impregnated with oil at ihe factory, so they needn't he soaked with oil prior to use. However, just as with natural oil stones, you'll need to add fresh oil before each use. All oil stones—natural and synthetic—are hard to reflatten once the surface becomes dished or worn. Typically, you flatten the stone by rubbing it on a Hat, oil-lubricated surface (such as plate glass) sprinkled with a coarse (240-grit) silicon carbide powder. You can also flatten oil stones on a large diamond benchstone or with a coarse silicon carbide sandpaper. Some old-timers flatten their oil stones by rubbing them on a flat concrete surface, although it takes quite a bit longer. Waterstones Waterstones cut faster than oil stones, come in the widest range of grits (from the roughest stones available to the finest) and arc t(l generally less expensive than natural oil stones. Also, because they use water as a lubricant, some woodworkers consider waterstones a "cleaner" stone lo work with: that is. they don't leave a residual oil film on the tool, which could contaminate the workpiece. As you would expect, you need to w ipe the tool dry alter sharpening to prevent rust. For these reasons, walerstones have largely replaced oil stones as multi-purpose sharpening slones in many shops. As w ith synthetic oil stones, most waterstones are made of graded, bonded abrasives, typically aluminum oxide or silicon carbide. Because the abrasive panicles are loosely bonded (called an open, or friable bond), waterstones are softer and more porous than oil stones. When you use ihe stone, sharp abrasive particles are released from its surface, which combine wilh ihe water to form a paste-like slurry. This action continually exposes fresh, sharp edges as you sharpen, which The Woodworker's Journal |