Woodworker's Journal 1994-18-5, страница 17

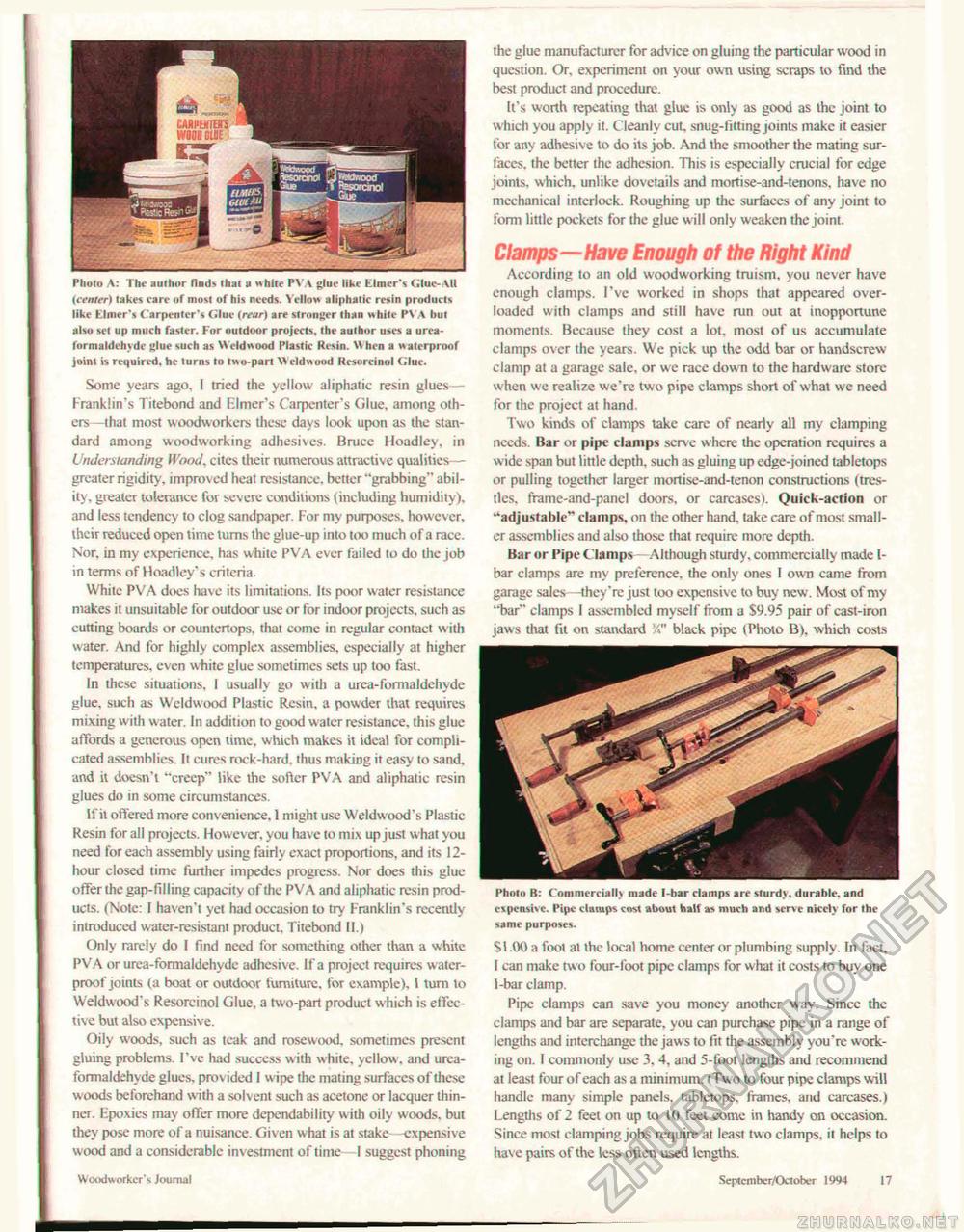

Photo A: The author finds that a white P\ A like timer's Glue-All (cenier) take* care of most of his needs. Yellow aliphatic resin products like timer's Carpenter's Clue (rear) are stronger ihnii »hitc PVA hm also sel up much faster. For outdoor projects, the author uses a urea-formaldehyde glue such as \Vefdwood Plastic Resin. W hen a » alerproof joint is required, he (urns lo two-part Welduood Kesorcinol (jlue. Some years ago, 1 tried the yellow aliphatic resin glues-Franklin's Titebond and Elmer's Carpenter's Glue, among others —that most woodworkers these days look upon as the standard among woodworking adhesives. Bruce Hoadley, in Understanding H ood, cites their numerous attractive qualities— greater rigidity, improved heat resistance, better "grabbing" ability, greater tolerance for severe conditions (including humidity), and less tendency lo clog sandpaper. For my purposes, however, their reduced open time turns the glue-up into too much of a race. Nor. in my experience, has white PVA ever failed to do the job in terms of Hoadley's criteria. White PVA docs have its limitations. Its poor water resistance makes it unsuitable for outdoor use or for indoor projects, such as cutting boards or countcrtops, that come in regular contact with water. And for highly complex assemblies, especially at higher temperatures, even white glue sometimes sets up too fast. In these situations, I usually go with a urea-formaldchyde glue, such as Wcldwood Plastic Resin, a powder that requires mixing with water. In addition to good water resistance, this glue affords a generous open time, which makes it ideal for complicated assemblies. It cures rock-hard, thus making it easy to sand, and it doesn't "creep" like the softer PVA and aliphatic resin glues do in some circumstances. If it offered more convenience, 1 might use Weidwood's Plastic Resin lor all projects. However, you have to mix up just what you need for each assembly using fairly exact proportions, and its 12hour closed time further impedes progress. Nor does this glue offer the gap-filling capacity of the PVA and aliphatic resin products. (Note: I haven't yet had occasion to try Franklin's recently introduced water-resistant product, Titebond 11.) Only rarely do I find need for something other than a white PVA or urea-formaldehyde adhesive. If a project requires waterproof joints (a boat or outdoor furniture, for example), I turn to Weidwood's Resorcinol Glue, a two-part product w hich is effective but also expensive. Oily woods, such as teak and rosewood, sometimes present gluing problems. I've had success with white, yellow, and urea-formaldehyde glues, provided 1 wipe the mating surfaces of these woods beforehand with a solvent such as acetone or lacquer thinner. Epoxies may offer more dependability with oily woods, but they pose more of a nuisance. Given what is at stake -expensive wood and a considerable investment of time I suggest phoning Woodworker" < Journal the glue manufacturer for advice on gluing the particular wood in question. Or, experiment on your own using scraps to find the best product and procedure. It's worth repeating that glue is only as good as the joint to w hich you apply it. Cleanly cut. snug-fitting joints make it easier for any adhesive to do its job. And the smoother the mating surfaces. the better the adhesion. This is especially crucial for edge joints, which, unlike dovetails and mortise-and-tenons, have no mechanical interlock. Roughing up the surfaces of any joint to form little pockets for the glue w ill only weaken the joint. Clamps—Have Enough of the Right Kind According to an old woodworking truism, you never have enough clamps. I've worked in shops that appeared overloaded with clamps and still have run out at inopportune moments. Because they cost a lot. most of us accumulate clamps over the years. We pick up the odd bar or handserew clamp at a garage sale, or we race down to the hardware store when we realize we're two pipe clamps short of what we need for the project at hand. Two kinds of clamps take care of nearly all iny clamping needs Bar or pipe clamps serve where the operation requires a wide span but little depth, such as gluing up edge-joined tabletops or pulling together larger mortise-and-tenon constructions (trestles. frame-and-panel doors, or carcases). Quick-action or "adjustable1" clamps, on the other hand, take care of most smaller assemblies and also those that require more depth. Bar ur Pipe Clamps—Although sturdy, commercially made l-bar clamps are my preference, the only ones I own came from garage sales they're just too expensive to buy new. Most of my "bar" clamps I assembled myself from a S9.95 pair of cast-iron jaws that fit on standard black pipe (Photo B), which costs Photo B: Commercial!) made I-bar clamps are sturdy, durable, and expensive. Pipe clamps cost about half as much and serve nicely for the same purposes. SI .00 a fool at the local home center or plumbing supply. In fact, I can make two four-foot pipe clamps for what it costs to buy one 1-bar clamp. Pipe clamps can save you money another way. Since the clamps and bar are separate, you can purchase pipe in a range of lengths and interchange the jaws to lit the assembly you're working on. I commonly use 3,4, 3nd 5-foot lengths and recommend at least four of each as a minimum. (Two to four pipe clamps will handle many simple panels, tabletops. frames, and carcases.) Lengths of 2 feet on up to 10 feet come in handy on occasion. Since most clamping jobs require at least two clamps, it helps to have pairs of the less often used lengths. September/October 1904 17 |