Woodworker's Journal 1980-4-5, страница 12

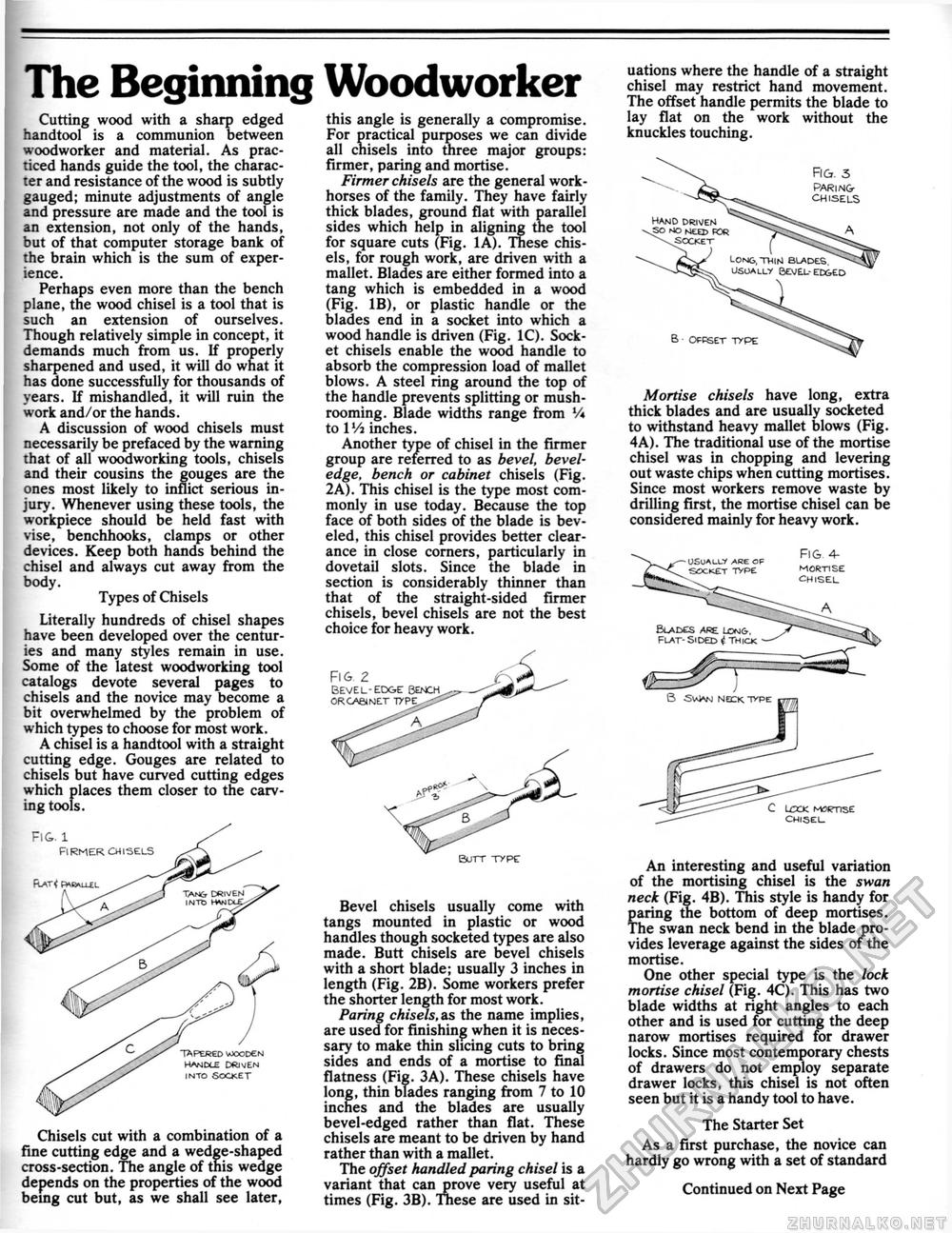

The Beginning Woodworker Cutting wood with a sharp edged handtool is a communion between woodworker and material. As practiced hands guide the tool, the character and resistance of the wood is subtly gauged; minute adjustments of angle and pressure are made and the tool is an extension, not only of the hands, but of that computer storage bank of the brain which is the sum of experience. Perhaps even more than the bench plane, the wood chisel is a tool that is such an extension of ourselves. Though relatively simple in concept, it demands much from us. If properly sharpened and used, it will do what it has done successfully for thousands of years. If mishandled, it will ruin the work and/or the hands. A discussion of wood chisels must necessarily be prefaced by the warning that of all woodworking tools, chisels and their cousins the gouges are the ones most likely to inflict serious injury. Whenever using these tools, the workpiece should be held fast with vise, benchhooks, clamps or other devices. Keep both hands behind the chisel and always cut away from the body. Types of Chisels Literally hundreds of chisel shapes have been developed over the centuries and many styles remain in use. Some of the latest woodworking tool catalogs devote several pages to chisels and the novice may become a bit overwhelmed by the problem of which types to choose for most work. A chisel is a handtool with a straight cutting edge. Gouges are related to chisels but have curved cutting edges which places them closer to the carving tools. Chisels cut with a combination of a fine cutting edge and a wedge-shaped cross-section. The angle of this wedge depends on the properties of the wood being cut but, as we shall see later, this angle is generally a compromise. For practical purposes we can divide all chisels into three major groups: firmer, paring and mortise. Firmer chisels are the general workhorses of the family. They have fairly thick blades, ground flat with parallel sides which help in aligning the tool for square cuts (Fig. 1A). These chisels, for rough work, are driven with a mallet. Blades are either formed into a tang which is embedded in a wood (Fig. IB), or plastic handle or the blades end in a socket into which a wood handle is driven (Fig. 1C). Socket chisels enable the wood handle to absorb the compression load of mallet blows. A steel ring around the top of the handle prevents splitting or mushrooming. Blade widths range from V* to IVj inches. Another type of chisel in the firmer group are referred to as bevel, bevel-edge, bench or cabinet chisels (Fig. 2A). This chisel is the type most commonly in use today. Because the top face of both sides of the blade is beveled, this chisel provides better clearance in close corners, particularly in dovetail slots. Since the blade in section is considerably thinner than that of the straight-sided firmer chisels, bevel chisels are not the best choice for heavy work. Butt typc Bevel chisels usually come with tangs mounted in plastic or wood handles though socketed types are also made. Butt chisels are bevel chisels with a short blade; usually 3 inches in length (Fig. 2B). Some workers prefer the shorter length for most work. Paring chisels,as the name implies, are used for finishing when it is necessary to make thin slicing cuts to bring sides and ends of a mortise to final flatness (Fig. 3A). These chisels have long, thin blades ranging from 7 to 10 inches and the blades are usually bevel-edged rather than flat. These chisels are meant to be driven by hand rather than with a mallet. The offset handled paring chisel is a variant that can prove very useful at times (Fig. 3B). TTiese are used in sit uations where the handle of a straight chisel may restrict hand movement. The offset handle permits the blade to lay flat on the work without the knuckles touching. Mortise chisels have long, extra thick blades and are usually socketed to withstand heavy mallet blows (Fig. 4A). The traditional use of the mortise chisel was in chopping and levering out waste chips when cutting mortises. Since most workers remove waste by drilling first, the mortise chisel can be considered mainly for heavy work. An interesting and useful variation of the mortising chisel is the swan neck (Fig. 4B). This style is handy for paring the bottom of deep mortises. The swan neck bend in the blade provides leverage against the sides of the mortise. One other special type is the lock mortise chisel (Fig. 4C). This has two blade widths at right angles to each other and is used for cutting the deep narow mortises required for drawer locks. Since most contemporary chests of drawers do not employ separate drawer locks, this chisel is not often seen but it is a handy tool to have. The Starter Set As a first purchase, the novice can hardly go wrong with a set of standard Continued on Next Page |