Woodworker's Journal 2009-33-4, страница 8

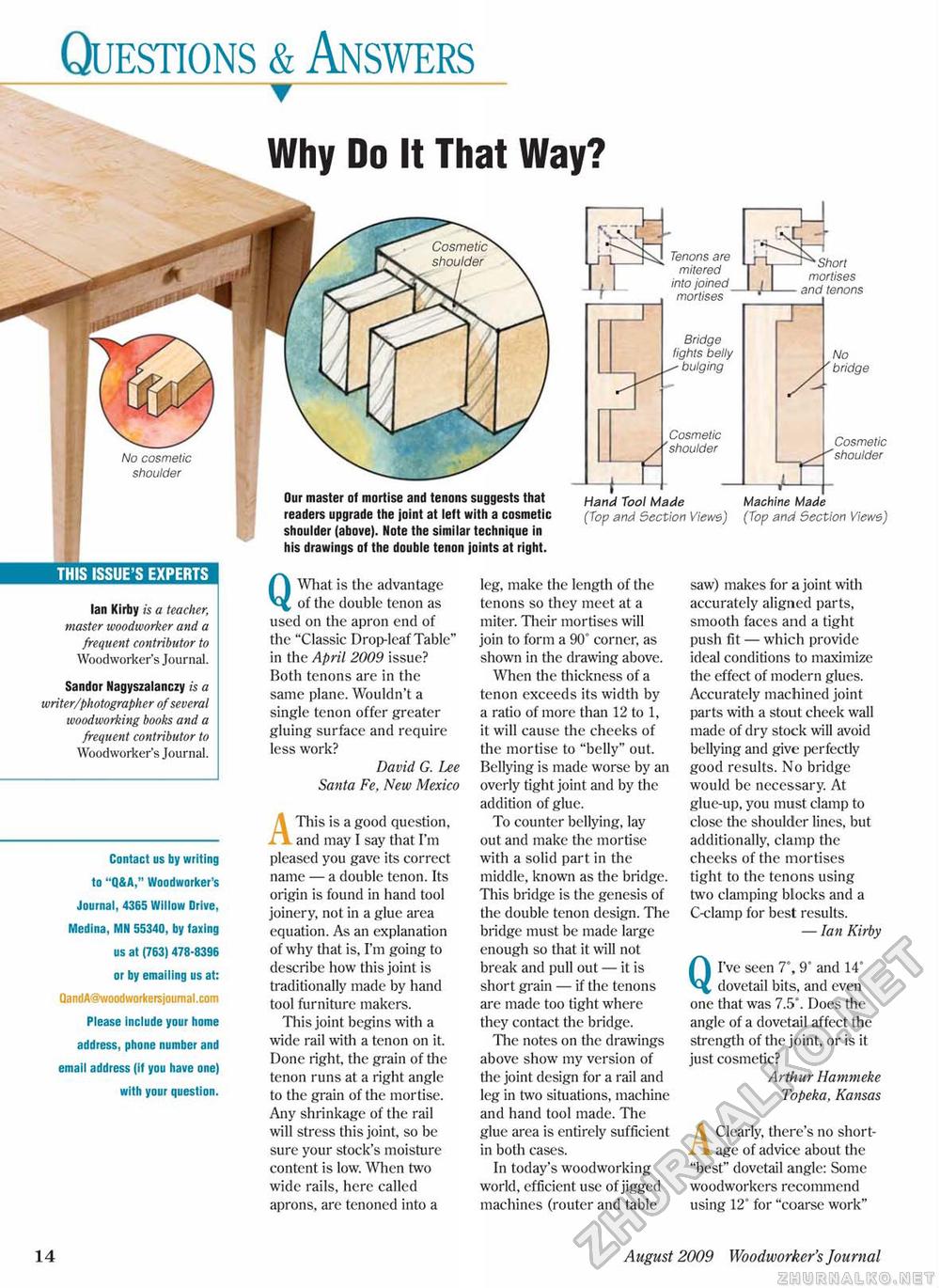

Questions & Answers Why Do It That Way? Our master of mortise and tenons suggests that readers upgrade the joint at left with a cosmetic shoulder (above). Note the similar technique in his drawings of the double tenon joints at right. Cosmetic shoulder Cosmetic 'shoulder Hand Tool Made (Top and Section Viewe) -JLJ-- Machine Made (Top and Section Views) Tenons are mitered into joined mortises Jhort mortises =nrl tenons Bridge fights belly bulging No ' bridge THIS ISSUE'S EXPERTS Contact us by writing to "Q&A," Woodworker's Journal, 4365 Willow Drive, Medina, MN 55340, by faxing us at(763)478-8396 or by emailing us at: QandA@woodworkersjoumal.com Please include your home address, phone number and email address (if you have one) with your question. QWhat is the advantage of the double tenon as used on the apron end of the "Classic Drop-leaf Table" in the April 2009 issue? Roth tenons are in the same plane. Wouldn't a single tenon offer greater gluing surface and require less work? David G. Lee Santa Fe, New Mexico A This is a good question, and may I say that I'm pleased you gave its correct name — a double tenon. Its origin is found in hand tool joinery, not in a glue area equation. As an explanation of why that is, I'm going to describe how this joint is traditionally made by hand tool furniture makers. This joint begins with a wide rail with a tenon on it. Done right, the grain of the tenon runs at a right angle to the grain of the mortise. Any shrinkage of the rail will stress this joint, so be sure your stock's moisture content is low. When two wide rails, here called aprons, arc tenoned into a leg, make the length of the tenons so they meet at a miter. Their mortises will join to form a 90° corner, as shown in the drawing above. When the thickness of a tenon exceeds its width by a ratio of more than 12 to 1, it will cause the cheeks of the mortise to "belly" out. Bellying is made worse by an overly tight joint and by the addition of glue. To counter bellying, lay out and make the mortise with a solid part in the middle, known as the bridge. This bridge is the genesis of the double tenon design. The bridge must be made large enough so that it will not break and pull out — it is short grain — if the tenons are made too tight where they contact the bridge. The notes on the drawings above show my version of the joint design for a rail and leg in two situations, machine and hand tool made. The glue area is entirely sufficient in both cases. In today's woodworking world, efficient use of jigged machines (router and table saw) makes for a joint with accurately aligned parts, smooth faces and a tight push fit — which provide ideal conditions to maximize the effect of modern glues. Accurately machined joint parts with a stout cheek wall made of dry stock will avoid bellying and give perfectly good results. No bridge would be necessary. At glue-up, you must clamp to close the shoulder lines, but additionally, clamp the cheeks of the mortises tight to the tenons using two clamping blocks and a C-clamp for best results. — Ian Kirby Ql've seen 7°, 9° and 14° dovetail bits, and even one that was 7.5°. Does the angle of a dovetail affect the strength of the joint, or is it just cosmetic? Arthur Hammeke Topeka, Kansas A Clearly, there's no shortage of advice about the "best" dovetail angle: Some woodworkers recommend using 12° for "coarse work" Ian Kirby is a teacher, master woodworker and a frequent contributor to Woodworker's Journal. Sandor Nagyszalanczy is a writer/photographer of several woodworking books and a frequent contributor to Woodworker's Journal. 14 August 2009 Woodworker's Journal |