Popular Woodworking 2005-11 № 151, страница 56

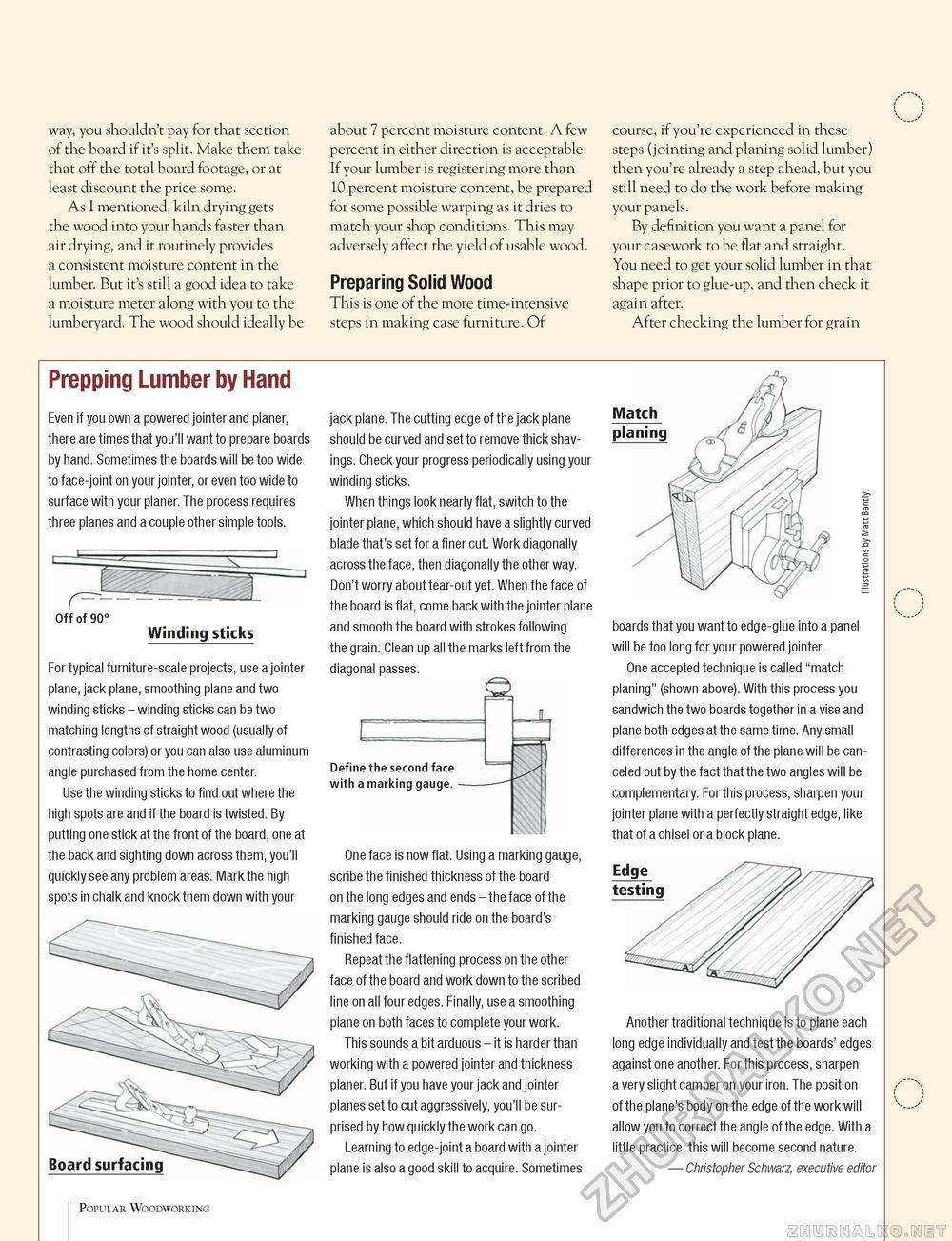

way, you shouldn't pay for that section of the board if it's split. Make them take that off the total board footage, or at least discount the price some. As I mentioned, kiln drying gets the wood into your hands faster than air drying, and it routinely provides a consistent moisture content in the lumber. But it's still a good idea to take a moisture meter along with you to the lumberyard. The wood should ideally be about 7 percent moisture content. A few percent in either direction is acceptable. If your lumber is registering more than 10 percent moisture content, be prepared for some possible warping as it dries to match your shop conditions. This may adversely affect the yield of usable wood. Preparing Solid Wood This is one of the more time-intensive steps in making case furniture. Of course, if you're experienced in these steps (jointing and planing solid lumber) then you're already a step ahead, but you still need to do the work before making your panels. By definition you want a panel for your casework to be flat and straight. You need to get your solid lumber in that shape prior to glue-up, and then check it again after. After checking the lumber for grain Prepping Lumber by Hand Even if you own a powered jointer and planer, there are times that you'll want to prepare boards by hand. Sometimes the boards will be too wide to face-joint on your jointer, or even too wide to surface with your planer. The process requires three planes and a couple other simple tools. Off of 90° Winding sticks For typical furniture-scale projects, use a jointer plane, jack plane, smoothing plane and two winding sticks - winding sticks can be two matching lengths of straight wood (usually of contrasting colors) or you can also use aluminum angle purchased from the home center. Use the winding sticks to find out where the high spots are and if the board is twisted. By putting one stick at the front of the board, one at the back and sighting down across them, you'll quickly see any problem areas. Mark the high spots in chalk and knock them down with your jack plane. The cutting edge of the jack plane should be curved and set to remove thick shavings. Check your progress periodically using your winding sticks. When things look nearly flat, switch to the jointer plane, which should have a slightly curved blade that's set for a finer cut. Work diagonally across the face, then diagonally the other way. Don't worry about tear-out yet. When the face of the board is flat, come back with the jointer plane and smooth the board with strokes following the grain. Clean up all the marks left from the diagonal passes. o o

One face is now flat. Using a marking gauge, scribe the finished thickness of the board on the long edges and ends - the face of the marking gauge should ride on the board's fi nished face. Repeat the flattening process on the other face of the board and work down to the scribed line on all four edges. Finally, use a smoothing plane on both faces to complete your work. This sounds a bit arduous - it is harder than working with a powered jointer and thickness planer. But if you have your jack and jointer planes set to cut aggressively, you'll be surprised by how quickly the work can go. Learning to edge-joint a board with a jointer plane is also a good skill to acquire. Sometimes boards that you want to edge-glue into a panel will be too long for your powered jointer. One accepted technique is called "match planing" (shown above). With this process you sandwich the two boards together in a vise and plane both edges at the same time. Any small differences in the angle of the plane will be canceled out by the fact that the two angles will be complementary. For this process, sharpen your jointer plane with a perfectly straight edge, like that of a chisel or a block plane. Another traditional technique is to plane each long edge individually and test the boards' edges against one another. For this process, sharpen a very slight camber on your iron. The position of the plane's body on the edge of the work will allow you to correct the angle of the edge. With a little practice, this will become second nature. — Christopher Schwarz, executive editor |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||