Woodworker's Journal 1993-17-5, страница 22

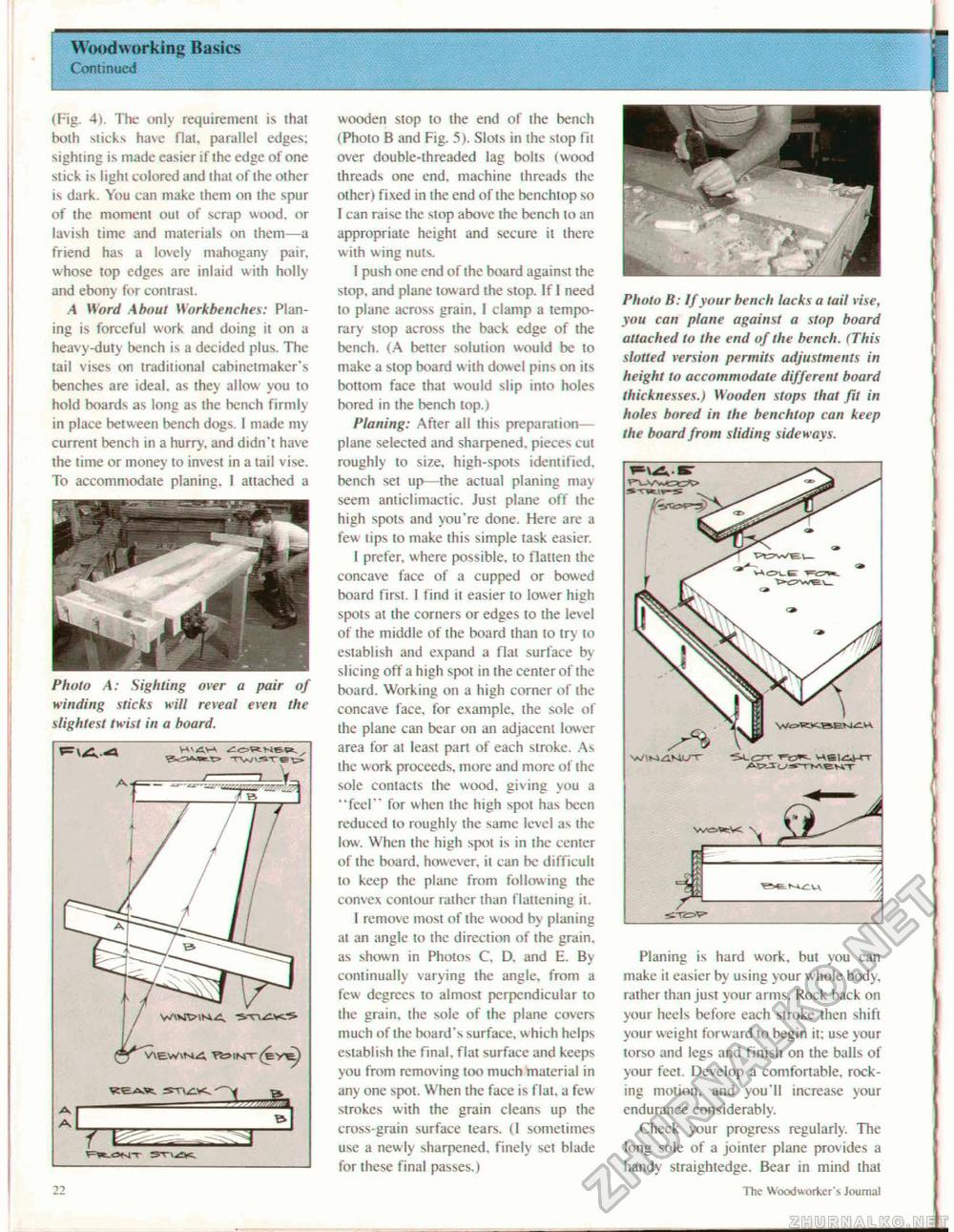

Woodworking Basics Continued wooden stop to the end of the bench (Photo B and Fig. 5). Slots in the stop fit over double-threaded lag bolts (wood threads one end. machine threads the other) fixed in the end of the benchtop so I can raise the stop above the bench to an appropriate height and secure it there with wing nuts. I push one end of the board against the stop, and plane toward the stop, (f I need to plane across grain. I clamp a temporary stop across the back edge of the bench. (A better solution would be to make a stop board with dowel pins on its bottom face that would slip into holes bored in the bench top.) Planing: After all this preparation— plane selected and sharpened, pieces cut roughly to size, high-spots identified, bench set up—the actual planing may seem anticlimactic. Just plane off the high spots and you're done. Here are a few tips to make this simple task easier. I prefer, where possible, to flatten the concave face of a cupped or bowed board first. I find it easier to lower high spots at the corners or edges to the level of the middle of the board than to try to establish and expand a flat surface by slicing off a high spot in the center of the board. Working on a high corner of the concave face, for example, the sole of the plane can bear on an adjacent lower area for at least part of each stroke. As the work proceeds, more and more of the sole contacts the wood, giving you a "feci" for when the high spot has been reduced to roughly the same level as the low. When the high spot is in the center of the board, however, it can he difficult to keep the plane from following the convex contour rather than flattening it. I remove most of the wood by planing at an angle to the direction of the grain, as shown in Photos C, D. and E. By continually varying the angle, from a few degrees to almost perpendicular to the grain, the sole of the plane covers much of the board's surface, which helps establish the final, flat surface and keeps you from removing too much material in any one spot. When the face is flat, a few strokes with the grain cleans up the cross-grain surface tears. (I sometimes use a newly sharpened, finely set blade for these final passes.) Planing is hard work, but you can make it easier by using your whole body, rather than just your arms. Rock back on your heels before each stroke then shift your weight forward to begin it; use your torso and legs and finish on the balls of your feet. Develop a comfortable, rocking motion, and you'll increase your endurance considerably. Check your progress regularly. The long sole of a jointer plane provides a handy straightedge. Bear in mind that 22 The Woodw orker'5 Journal (Fig. 4). The only requirement is that both sticks have flat, parallel edges; sighting is made easier if the edge of one stick is light colored and that of the other is dark. You can make them on the spur of the moment out of scrap wood, or lavish time and materials on them—a friend has a lovely mahogany pair, whose top edges are inlaid with holly and ebony for contrast. ,4 Word About Workbenches: Planing is forceful work and doing it on a heavy-duty bench is a decided plus. The tail vises on traditional cabinetmaker's benches are ideal, as they allow you to hold boards as long as the bench firmly in place between bench dogs. I made my current bench in a hurry, and didn't have the time or money to invest in a tail vise. To accommodate planing. ! attached a Photo .4: Sighting over a pair of winding sticks Kill reveal even the slightest twist in a board. Photo B: If your bench lacks a tail vise, you can plane against a stop board attached to the end of the bench. (This slotted version permits adjustments in height to accommodate different board thicknesses.) Wooden stops that fit in holes bored in the benchtop can keep the board from sliding sideways. _ - VAei^H-r AsjJo'rf-rMevAT- |