Woodworker's Journal 2006-30-5, страница 21

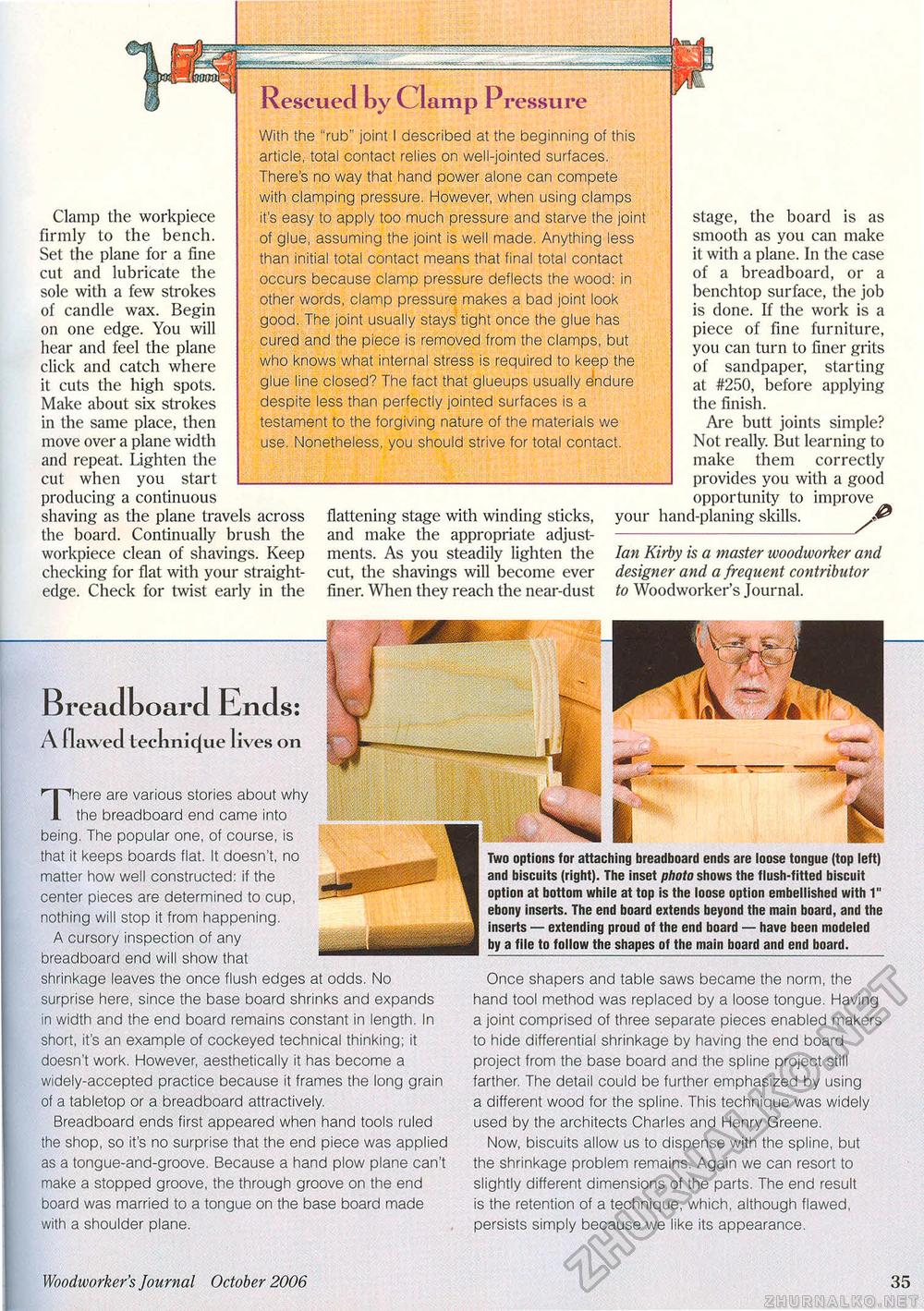

Clamp the workpiece firmly to the bench. Set the plane for a fine cut and lubricate the sole with a few strokes of candle wax. Begin on one edge. You will hear and feel the plane click and catch where it cuts the high spots. Make about six strokes in the same place, then move over a plane width and repeat. Lighten the cut when you start producing a continuous shaving as the plane travels across the board. Continually brush the workpiece clean of shavings. Keep checking for flat with your straightedge. Check for twist early in the Rescued by Clamp Pressure With the "rub" joint I described at the beginning of this article, total contact relies on well-jointed surfaces. There's no way that hand power alone can compete with clamping pressure. However, when using clamps it's easy to apply too much pressure and starve the joint of glue, assuming the joint is well made. Anything less than initial total contact means that final total contact occurs because clamp pressure deflects the wood: in other words, clamp pressure makes a bad joint look good. The joint usually stays tight once the glue has cured and the piece is removed from the clamps, but who knows what internal stress is required to keep the glue line closed? The fact that glueups usually endure despite less than perfectly jointed surfaces is a testament to the forgiving nature of the materials we use. Nonetheless, you should strive for total contact. flattening stage with winding sticks, and make the appropriate adjustments. As you steadily lighten the cut, the shavings will become ever finer. When they reach the near-dust stage, the board is as smooth as you can make it with a plane. In the case of a breadboard, or a benchtop surface, the job is done. If the work is a piece of fine furniture, you can turn to finer grits of sandpaper, starting at #250, before applying the finish. Are butt joints simple? Not really. But learning to make them correctly provides you with a good opportunity to improve your hand-planing skills. Ian Kirby is a master woodworker and designer and a frequent contributor to Woodworker's Journal. Breadboard Ends: Two options for attaching breadboard ends are loose tongue (top left) and biscuits (right). The inset photo shows the flush-fitted biscuit option at bottom while at top is the loose option embellished with 1" ebony inserts. The end board extends beyond the main board, and the inserts — extending proud of the end board — have been modeled by a file to follow the shapes of the main board and end board. Once shapers and table saws became the norm, the hand tool method was replaced by a loose tongue. Having a joint comprised of three separate pieces enabled makers to hide differential shrinkage by having the end board project from the base board and the spline project still farther. The detail could be further emphasized by using a different wood for the spline. This technique was widely used by the architects Charles and Henry Greene. Now, biscuits allow us to dispense with the spline, but the shrinkage problem remains. Again we can resort to slightly different dimensions of the parts. The end result is the retention of a technique, which, although flawed, persists simply because we like its appearance. 35 A Hawed technique lives on There are various stories about why the breadboard end came into being. The popular one, of course, is that it keeps boards flat, it doesn't, no matter how well constructed: if the center pieces are determined to cup, nothing will stop it from happening. A cursory inspection of any breadboard end will show that shrinkage leaves the once flush edges at odds. No surprise here, since the base board shrinks and expands in width and the end board remains constant in length. In short, it's an example of cockeyed technical thinking; it doesn't work. However, aesthetically it has become a widely-accepted practice because it frames the long grain of a tabletop or a breadboard attractively. Breadboard ends first appeared when hand tools ruled the shop, so it's no surprise that the end piece was applied as a tongue-and-groove. Because a hand plow plane can't make a stopped groove, the through groove on the end board was married to a tongue on the base board made with a shoulder plane. Woodworker's Journal October 2006 |