Woodworker's Journal 2006-30-5, страница 23

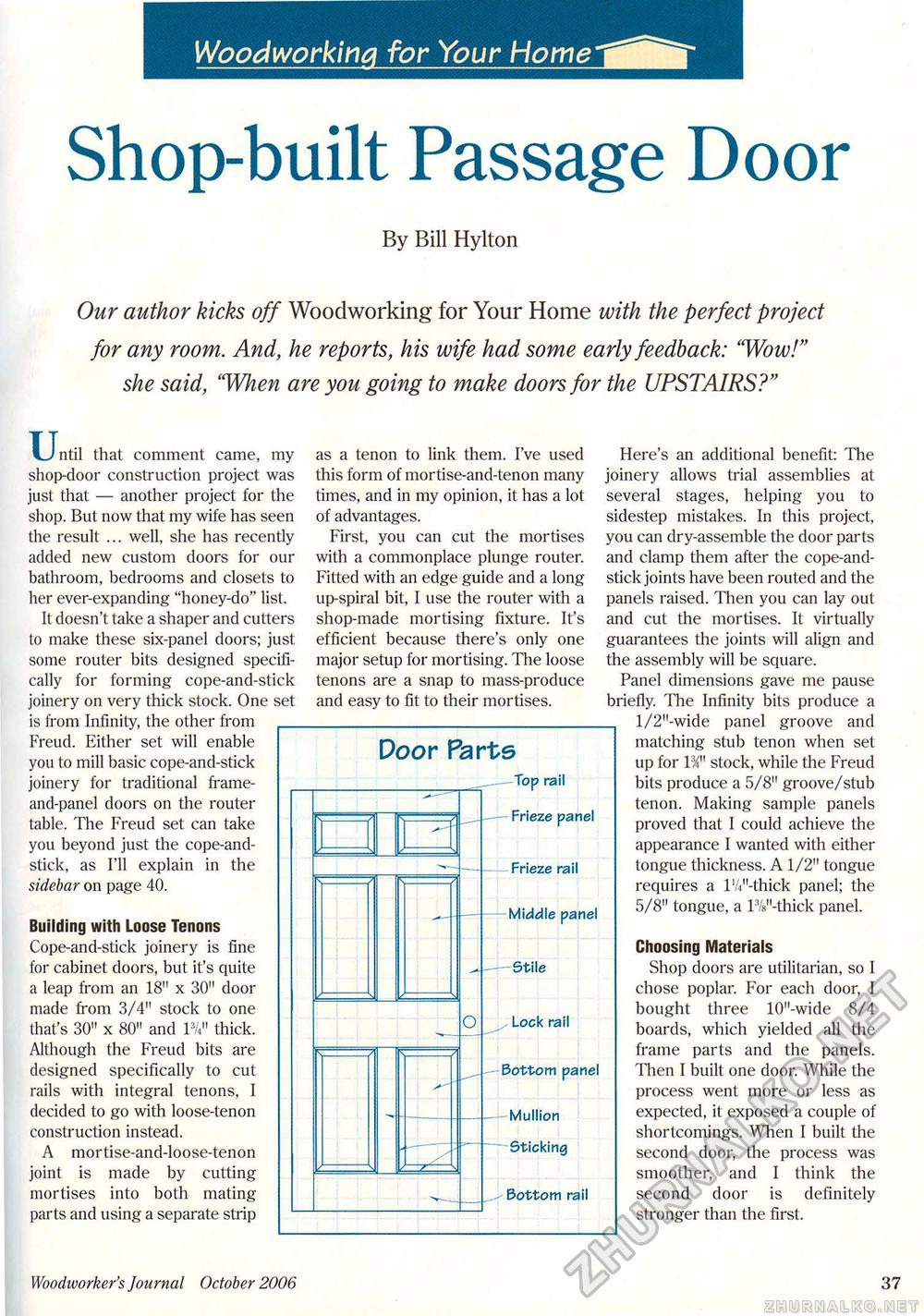

Shop-built Passage Door By Bill HyltonOur author kicks off Woodworking for Your Home with the perfect project for any room. And, he reports, his wife had some early feedback: "Wow!" she said, 'When are you going to make doors for the UPSTAIRS?" U, ntil that comment came, my shop-door construction project was just that — another project for the shop. But now that my wife has seen the result ... well, she has recently added new custom doors for our bathroom, bedrooms and closets to her ever-expanding "honey-do" list. It doesn't take a shaper and cutters to make these six-panel doors; just some router bits designed specifically for forming cope-and-stick joinery on very thick stock. One set is from Infinity, the other from Freud. Either set will enable you to mill basic cope-and-stick joinery for traditional frame-and-panel doors on the router table. The Freud set can take you beyond just the cope-and-stick, as I'll explain in the sidebar on page 40. Building with Loose Tenons Cope-and-stick joinery is fine for cabinet doors, but it's quite a leap from an 18" x 30" door made from 3/4" stock to one that's 30" x 80" and 13A" thick. Although the Freud bits are designed specifically to cut rails with integral tenons, I decided to go with loose-tenon construction instead. A mortise-and-loose-tenon joint is made by cutting mortises into both mating parts and using a separate strip as a tenon to link them. I've used this form of mortise-and-tenon many times, and in my opinion, it has a lot of advantages. First, you can cut the mortises with a commonplace plunge router. Fitted with an edge guide and a long up-spiral bit, I use the router with a shop-made mortising fixture. It's efficient because there's only one major setup for mortising. The loose tenons are a snap to mass-produce and easy to fit to their mortises. Door Parts Here's an additional benefit: The joinery allows trial assemblies at several stages, helping you to sidestep mistakes. In this project, you can dry-assemble the door parts and clamp them after the cope-and-stick joints have been routed and the panels raised. Then you can lay out and cut the mortises. It virtually guarantees the joints will align and the assembly will be square. Panel dimensions gave me pause briefly. The Infinity bits produce a l/2"-wide panel groove and matching stub tenon when set up for 1%" stock, while the Freud bits produce a 5/8" groove/stub tenon. Making sample panels proved that I could achieve the appearance I wanted with either tongue thickness. A 1/2" tongue requires a r/i"-thick panel; the 5/8" tongue, a lV-thick panel. Choosing Materials Shop doors are utilitarian, so I chose poplar. For each door, I bought three 10"-wide 8/4 boards, which yielded all the frame parts and the panels. Then I built one door. While the process went more or less as expected, it exposed a couple of shortcomings. When I built the second door, the process was smoother, and I think the second door is definitely stronger than the first. Woodworker's Journal October 2006 37 |