Woodworker's Journal 2006-30-5, страница 24

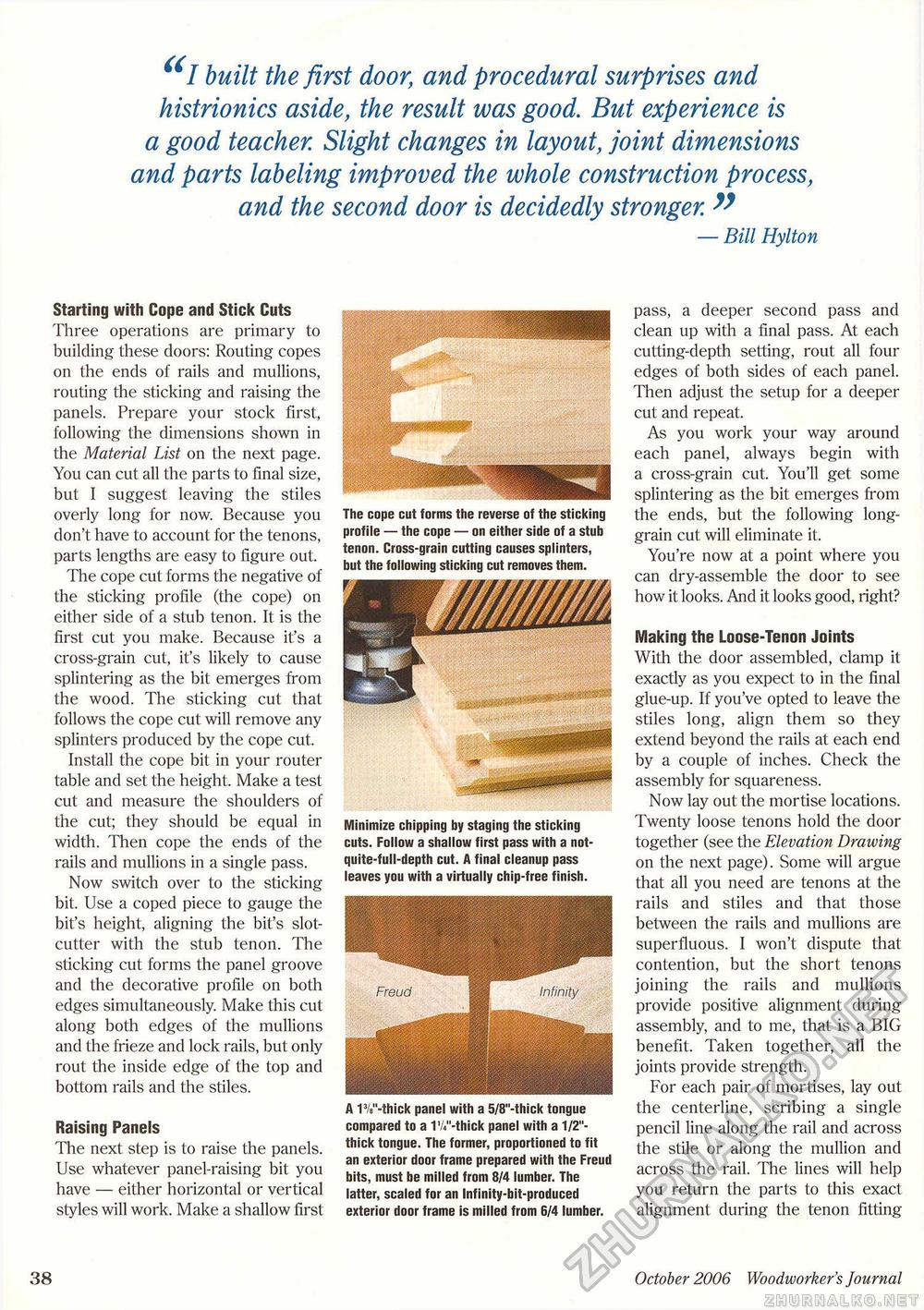

built the first door; and procedural surprises and histrionics aside, the result was good. But experience is a good teacher. Slight changes in layout, joint dimensions and parts labeling improved the whole construction process, and the second door is decidedly stronger. » — Bill Hylton Starting with Cope and Stick Cuts Three operations are primary to building these doors: Routing copes on the ends of rails and mullions, routing the sticking and raising the panels. Prepare your stock first, following the dimensions shown in the Material List on the next page. You can cut all the parts to final size, but I suggest leaving the stiles overly long for now. Because you don't have to account for the tenons, parts lengths are easy to figure out. The cope cut forms the negative of the sticking profile (the cope) on either side of a stub tenon. It is the first cut you make. Because it's a cross-grain cut, it's likely to cause splintering as the bit emerges from the wood. The sticking cut that follows the cope cut will remove any splinters produced by the cope cut. Install the cope bit in your router table and set the height. Make a test cut and measure the shoulders of the cut; they should be equal in width. Then cope the ends of the rails and mullions in a single pass. Now switch over to the sticking bit. Use a coped piece to gauge the bit's height, aligning the bit's slot-cutter with the stub tenon. The sticking cut forms the panel groove and the decorative profile on both edges simultaneously. Make this cut along both edges of the mullions and the frieze and lock rails, but only rout the inside edge of the top and bottom rails and the stiles. Raising Panels The next step is to raise the panels. Use whatever panel-raising bit you have — either horizontal or vertical styles will work. Make a shallow first The cope cut forms the reverse of the sticking profile — the cope — on either side of a stub tenon. Cross-grain cutting causes splinters, but the following sticking cut removes them. Minimize chipping by staging the sticking cuts. Follow a shallow first pass with a not-quite-full-depth cut. A final cleanup pass leaves you with a virtually chip-free finish. A W-thick panel with a 5/8"-thick tongue compared to a 1 V-thick panel with a 1/2"-thick tongue. The former, proportioned to fit an exterior door frame prepared with the Freud bits, must be milled from 8/4 lumber. The latter, scaled for an Infinity-bit-produced exterior door frame is milled from 6/4 lumber. pass, a deeper second pass and clean up with a final pass. At each cutting-depth setting, rout all four edges of both sides of each panel. Then adjust the setup for a deeper cut and repeat. As you work your way around each panel, always begin with a cross-grain cut. You'll get some splintering as the bit emerges from the ends, but the following long-grain cut will eliminate it. You're now at a point where you can dry-assemble the door to see how it looks. And it looks good, right? Making the Loose-Tenon Joints With the door assembled, clamp it exactly as you expect to in the final glue-up. If you've opted to leave the stiles long, align them so they extend beyond the rails at each end by a couple of inches. Check the assembly for squareness. Now lay out the mortise locations. Twenty loose tenons hold the door together (see the Elevation Drawing on the next page). Some will argue that all you need are tenons at the rails and stiles and that those between the rails and mullions are superfluous. I won't dispute that contention, but the short tenons joining the rails and mullions provide positive alignment during assembly, and to me, that is a BIG benefit. Taken together, all the joints provide strength. For each pair of mortises, lay out the centerline, scribing a single pencil line along the rail and across the stile or along the mullion and across the rail. The lines will help you return the parts to this exact alignment during the tenon fitting 38 October 2006 Woodivorker's Journal |