Creative Woodworks & crafts 2001-03, страница 40

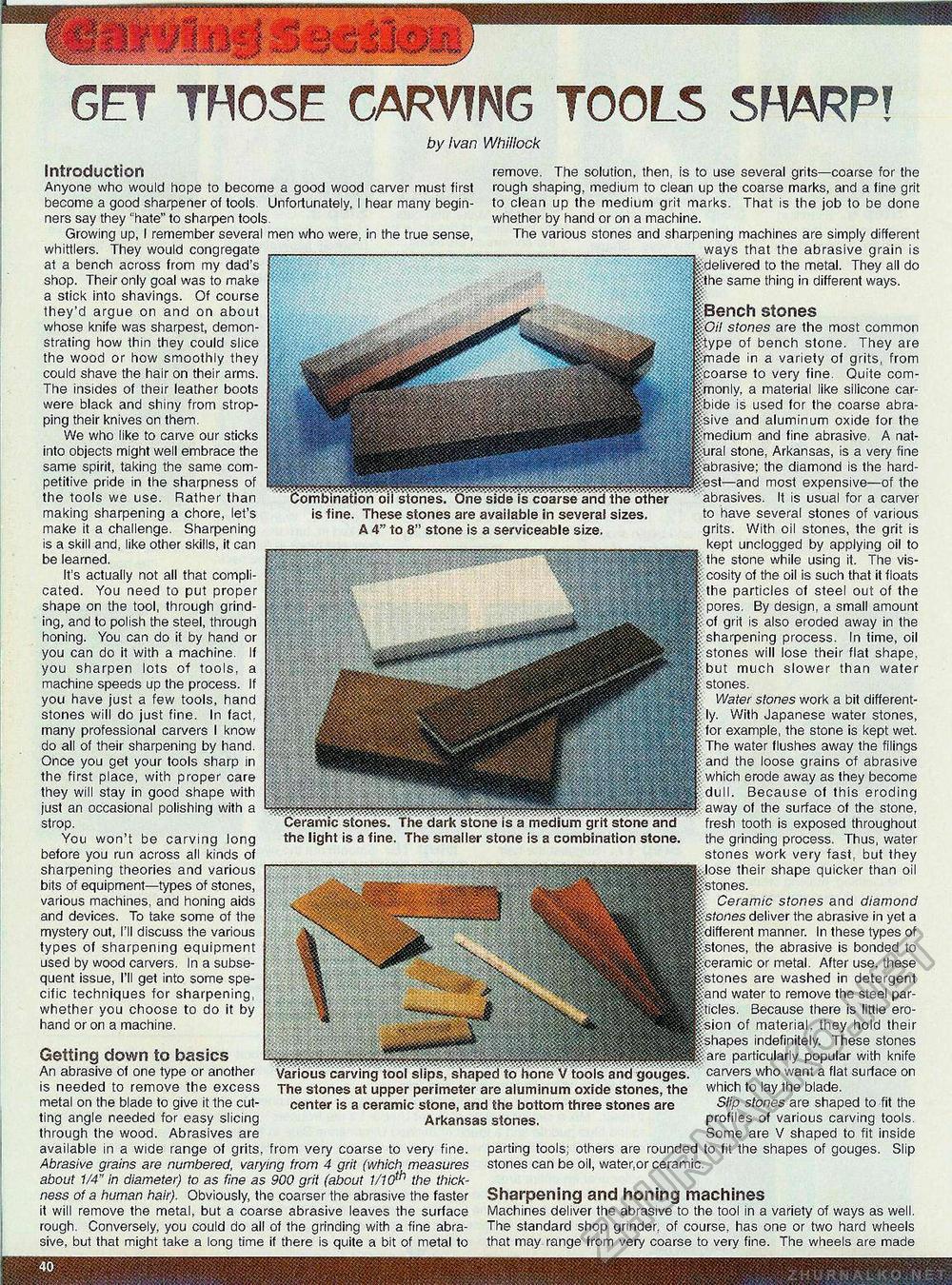

5E rn TNG TOOLS 5WW by Ivan Whillock Introduction Anyone who would hope to become a good wood carver must first become a good sharpener of tools. Unfortunately, I hear many beginners say they "hate" to sharpen tools. Growing up, I remember several men who were, in the true sense, whittlers. They would congregate at a bench across from my dad's shop. Their only goal was to make a stick into shavings. Of course they'd argue on and on about whose knife was sharpest, demonstrating how thin they could slice the wood or how smoothly they could shave the hair on their arms. The insides of their leather boots were black and shiny from stropping their knives on them. We who like to carve our sticks into objects might well embrace the same spirit, taking the same competitive pride in the sharpness of the tools we use. Rather than making sharpening a chore, let's make it a challenge. Sharpening is a skill and, like other skills, it can be learned. It's actually not all that complicated. You need to put proper shape on the tool, through grinding, and to polish the steel, through honing. You can do it by hand or you can do it with a machine. If you sharpen lots of tools, a machine speeds up the process. If you have just a few tools, hand stones will do just fine. In fact, many professional carvers I know do all of their sharpening by hand. Once you get your tools sharp in the first place, with proper care they will stay in good shape with just an occasional polishing with a strop. You won't be carving long before you run across all kinds of sharpening theories and various bits of equipment—types of stones, various machines, and honing aids and devices. To take some of the mystery out, I'll discuss the various types of sharpening equipment used by wood carvers. In a subsequent issue, I'll get into some specific techniques for sharpening, whether you choose to do it by hand or on a machine. Combination oii stones. One side is coarse arid the other is fine. These stones are available in several sizes A 4" to 8" stone is a serviceable size. Ceramic stones. The dark stone is a medium grit stone and the light is a fine. The smaller stone is a combination stone, Getting down to basics An abrasive of one type or another is needed to remove the excess metal on the blade to give it the cutting angle needed for easy slicing through the wood. Abrasives are available in a wide range of grits, from very coarse to very fine. Abrasive grains are numbered, varying from 4 grit (which measures about 1/4" in diameter) to as fine as 900 grit (about 1/10th the thickness of a human hair). Obviously, the coarser the abrasive the faster it will remove the metal, but a coarse abrasive leaves the surface rough. Conversely, you could do all of the grinding with a fine abrasive, but that might take a long time if there is quite a bit of metal to remove. The solution, then, is to use several grits—coarse for the rough shaping, medium to clean up the coarse marks, and a fine grit to clean up the medium grit marks. That is the job to be done whether by hand or on a machine. The various stones and sharpening machines are simply different ways that the abrasive grain is delivered to the metal. They all do ■the same thing in different ways. Bench stones Oil stones are the most common type of bench stone. They are imade in a variety of grits, from Ulcoarse to very fine. Quite com-" ''monly, a material like silicone car-:bide is used for the coarse abrasive and aluminum oxide for the ^medium and fine abrasive. A natural stone, Arkansas, is a very fine ^abrasive; the diamond is the hardest—and most expensive—of the abrasives. It is usual for a carver to have several stones of various grits. With oil stones, the grit is kept unclogged by applying oil to t the stone while using it. The viscosity of the oil is such that it floats : the particles of steel out of the pores. By design, a small amount i of grit is also eroded away in the sharpening process. In time, oil f: stones will lose their flat shape, but much slower than water stones. Water stones work a bit differently. With Japanese water stones, for example, the stone is kept wet. The water flushes away the filings | and the loose grains of abrasive which erode away as they become dull. Because of this eroding } away of the surface of the stone, fresh tooth is exposed throughout the grinding process. Thus, water stones work very fast, but they lose their shape quicker than oil £stones. Ceramic stones and diamond ■tstones deliver the abrasive in yet a ^different manner. In these types of £stones, the abrasive is bonded to ^ceramic or metal. After use, these fStones are washed in detergent £and water to remove the steel parotides. Because there is little erosion of material, they hold their i.shapes indefinitely. These stones £are particularly popular with knife carvers who want a flat surface on which to lay the blade. Slip stones are shaped to fit the profiles of various carving tools. Some are V shaped to fit inside parting tools: others are rounded to fit the shapes of gouges. Slip stones can be oil, water,or ceramic. Sharpening and honing machines Machines deliver the abrasive to the tool in a variety of ways as well. The standard shop grinder, of course, has one or two hard wheels that may range from very coarse to very fine. The wheels are made Various carving tool slips, shaped to hone V tools and gouges. The stones at upper perimeter are aluminum oxide stones, the center is a ceramic stone, and the bottom three stones are Arkansas stones. |